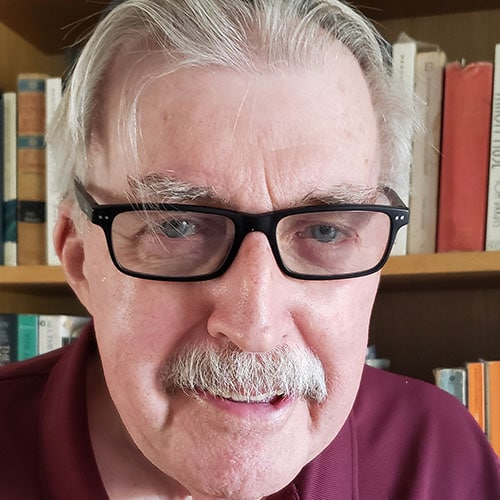

If there’s one thing that’s characterized Temple Beth David’s Rabbi Nancy Myers‘ career, it’s her persistence. When she was ordained by Hebrew Union College in the early part of the 2000s, it was not easy being a female rabbi.

But before she went out looking for a job, the Buffalo, New York native asked her colleagues for advice. “Since I was new, I asked colleagues in the field. She asked “what senior rabbis I should work with and who to avoid. Some senior rabbis, especially ones with great names, can be terrible to work with. Colleagues directed me to the mensches.”

One of the mensches she was directed to was Rabbi Steve Hart at Temple Chai in the Chicago suburb of Long Grove. “I was looking for a mensch, someone where I wouldn’t be the dog the senior rabbi would kick,” she said. “Steve Hart was indeed a mensch. I was the first female rabbi in the northwest suburbs of Chicago.” Myers said she values her suburban Chicago days “because I learned a lot about healthy temple teams where there is a real partnership between lay leaders and the clergy – as opposed to a hierarchical model.”

But after six years, she was looking for new challenges. By 2003, she said, “I wanted my own synagogue.” Her strengths, she said, are “teaching, preaching, leadership and pastoral care.” But it was harder than she imagined. “Becoming an assistant associate? Very desirable,” she said. “I know that because I was told it behind the scenes.”

At one Philadelphia congregation she was told “we are not sure we’re ready for a woman rabbi.” At a congregation in Chicago, she was being fast-tracked to be the new rabbi. Suddenly, the process slowed. Myers clearly remembers the scene in the temple’s rabbi emeritus’ dark office. “He said 12 words that slammed the door: ‘Nancy, you’re one of the bright ones. But there’s a female cantor.’”

Her disappointed but sharp reply: “Ahh, there’s too much estrogen on the bimah!”

The rabbi explained that because Myers was a woman, board members were worried she wouldn’t be strong enough with problematic lay leadership. She fired back: “I told him, ‘What a shame because that is not my weakness.’” The executive director of the Board of Rabbis in Chicago told her she could sue, but that did not appeal.

Returning to Buffalo did appeal, but there wasn’t a good congregational match. She realized she was looking to replicate her Temple Chai experience. “I certainly found it here,” she said on a sunny afternoon in Orange County. She especially loves the music program, which she calls “exceptional … I came from a large temple and they didn’t have the music program we have here.”

She said Temple Beth David “did the most thorough interview process here of any temple I have dealt with,” she said. “They flew me out for a number of days and many interviews.” She was impressed that Beth David leaders “were and are very down to earth.” And she has become Temple Beth David’s longest-serving rabbi.

But things did not start off so auspiciously. During her first High Holy Days at Beth David, “quite an incident” occurred. At her first Erev Rosh Hashanah service, she was giving a sermon about the prisoner abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib in Iraq. “I was 34 years old,” she said, “perceived as young, and obviously I am a woman. I was told behind the scenes people weren’t sure they were ready for a woman rabbi.”

The place was packed, she said. Then, “a man walks down the aisle, motioning for a time out. I’m thinking, ‘Wow! Someone must have had a heart attack. That’s happened before.’ I stop speaking. He starts to yell ‘You have no right to be up there! You have no right to be talking politics on the pulpit. This is wrong!’ and he’s going off.

“My very first Rosh Hashanah. I am stunned. Not sure what to do with this. I look back at (the temple’s) president. His face is shocked, too. I’m thinking, ‘if this man is speaking for everyone, I have to close my machzor and off the bimah I go. I am done here.’”

The seconds slowly ticked by until another person in the congregation stood up and said “I was finding very meaningful what the rabbi was saying, and I want her to finish.” There was limited applause. “That’s all I needed to know,” she thought, “that I wasn’t alone.”

She took the mic and said ‘I, as the rabbi, when I give a sermon, I do not purport to speak on behalf of all of you. I don’t expect all of you to agree with what I am saying. But the time to disagree is afterward. I think it’s an important part of a rabbi’s mission to speak about lofty rabbinical texts and God, but it’s part of a rabbi’s mission to talk about current issues affecting us, and to talk about history and archeology and psychology and science. All of them belong in a sermon.”

Twenty-one years later, Rabbi Myers reflected on that moment. “What came out of that – that was good – was that people who didn’t like the contents of my sermon, liked the way I handled it.”

“I think it’s an important part of a rabbi’s mission to speak about lofty rabbinical texts and God, but it’s part of a rabbi’s mission to talk about current issues affecting us.”

Fast Takes with Rabbi Myers

Jewish Journal: What do you do on your day off?

Rabbi Myers: Nothing terribly exciting. Pilates, gardening, I love to cook, salads, soups, stews, chicken, fish…everything, I also bake and I catch up on bills.

J.J.: Your favorite Jewish food?

R.M. : I make a great chicken soup, but I don’t really have one.

J.J.: Your favorite moment of the week?

R.M. : Sometimes at services when the cantor and choir are singing something beautiful, I feel how blessed I am to be here.

Three years ago, Myers set out to write a novel about Israelites struggling for survival – led by the rarest ancient hero, a woman – in the early 13th century B.C.E.

Don’t turn away, as I did at first, because this lady knows how to tell a compelling story, especially to skeptics.

Rabbi Myers connects in “Awake, Awake, Deborah!” by deploying language as fresh and appealing as early-morning milk or the funniest show on television last night.

The book opens shortly after 1200 B.C.E when ancient Israelites first came into history in an extra biblical sense, but in a familiar position. First mentioned by the conquering Merneptah, an Egyptian Pharoah, 1209 B.C.E., he wrote that Israel “was laid to waste and his seed not.”

Myers alludes to the Book of Judges one-sidedly identifying “men of skill, strategy and might.” Only one woman was listed, Deborah, “who has two whole chapters, four and five, devoted to her leadership in a time of great danger to the Israelites.”

During a sabbatical from her Orange County shul, Rabbi Myers penned “Awake, Awake, Deborah!” because “I always have been fascinated with Deborah,” she told The Journal.

“She is the only female judge listed in the Book of Judges. I have wondered how a woman could have risen to leadership during a time when women didn’t function in these kinds of roles.”

Why this book? Because she loves biblical history and archeology.

“I wanted to fuse my knowledge in an engaging, entertaining novel.”

In an article for the Central Conference of American Rabbis, Myers wrote about her book and a study guide she wrote with a friend. Briefly, she describes a typical Israeli struggle:

“As the Israelites struggled for survival, they had to contend with differing groups of Canaanites, as well as the Sea Peoples from Greece who invaded the coast. According to Jo Ann Hackett, there was a lack of centralization in society and no permanent administration, not even a standing army. And so, we have an opening for unlikely leaders such as outcast men and even a woman to rise to power. Perhaps it is because of this time of upheaval that the Israelites of the early Iron Age were willing to allow a woman to lead them and help them survive. Everything was in tumult.”