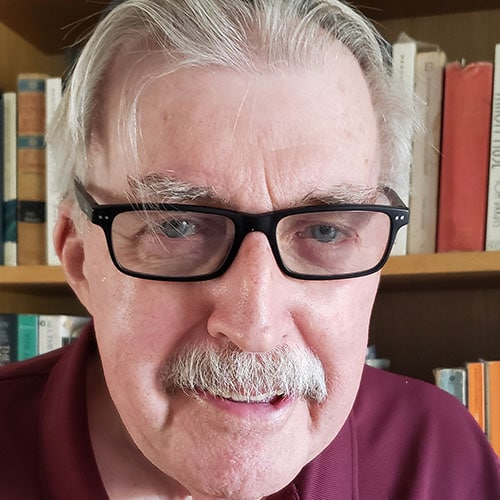

When Rabbi Abraham Lieberman entered Brooklyn College, he knew he was sure of his goal: He was going to be a psychiatrist. Informed this would require 16 years of schooling, he immediately said, “No way.” A friend suggested, ““Do the next best thing. Be a psychologist.”“ That idea resonated with Lieberman, but “for a whole bunch of reasons, I was disappointed.”

While he was figuring out his next career move, a friend who was teaching at a Jewish day school on Long Island was planning a brief trip to Israel. He asked Lieberman to sub for him while he was gone. “My friend said he would be gone for a few weeks,” Lieberman said. “He said the school told him if he found a sub, he’d get his job back when he returned. If not, there would be a job opening.” That he had never taught before wouldn’t be a problem.

Once inside the classroom though, Lieberman found an immediate home. “That experience changed everything,” he said. He immediately forgot about psychology and decided he was going to be a teacher.

“When they get it, the light bulb comes through the eyes. … I thought, this is what I want to do. So this is what I did.”

Decades later, Rabbi Lieberman’s achievements stand nearly as tall as his multi-story, 13,000-volume Jewish library. It is a monument to his lifetime of teaching Torah to teenagers and, time permitting, engaging in research by plunging centuries deep into Jewish history. What about the classroom that caught the rabbi’s attention? What drew him was “the sparkle in the eyes of the students who realized how wonderful Torah could be,” he said. “This experience spoke to me. I said ‘Wow! This is good stuff.’” Telling the story, Lieberman’s face lit up, the memory still sparking joy. “The sparkle in the students made an impression,” he said. “They got it. I knew they got it. I was like, whoa! When they get it, the light bulb comes through the eyes. They have it.” From that point on, there was no doubt in his mind. “I thought, this is what I want to do. So this is what I did.”

He has never regretted his career decision, he said. In fact, Lieberman sees a “total link” between teaching and psychology. “You are engaging with people, and you do listen and hear what they are dealing with, the empathy of what students are going through. I guess the reason I wanted to do psychology was because I wanted to be around people. It really works.” Widely regarded as an expert on Jewish history, Rabbi Lieberman led two girls’ Jewish high schools – including YULA – before joining the Shalhevet faculty in 2017. He has invested most of his professional life teaching young women. “Teaching young women has been a privilege,” he said. Had his friends’ views prevailed, it might not have turned out this way. When Lieberman started teaching girls, some of them turned up their noses. “They said ‘Teaching girls? Don’t you want to…?’ I answered ‘No, let’s try this out.’”

He loved it. “Teaching girls was an eye-opener because I never – coming from an all-boys school, only having a brother and not sisters … Suddenly seeing how young women think, and their much earlier maturity in life” took the young rabbi by surprise. Speaking frankly, he said, “young women mature much earlier. The ninth-grade young woman tends to have more depth than a boy who is still trying to figure it out at that stage. The boys come to it a little later.”

What would God’s explanation for that be? The rabbi turned to a quote from the Talmud: “More understanding was given to women than to men.” He said it can be called women’s intuition. “They are much more practical,” Lieberman said. “They are more likely to see a problem for what it is – without veering off into different thoughts.” Asked if he teaches boys and girls any differently, the rabbi said he does not see a difference … except for, perhaps, one. Teaching girls, he said, requires “a drop more of practicality.” By way of explanation, he said “if a boy asks a question, depending on his background, I start saying ‘Well, in Rashi, one opinion says this and one opinion says that.’” But girls, he said, “understand that I am generalizing. They will say, ‘I understand there are disagreements, but, practically, what do I need to do?’ “The girls will say, ‘This rabbi said … That rabbi said … But give it to me straight.’”

When asked how much has changed in learning by boys or girls over the decades, he insisted “the environment around us changes tremendously,” but the human spirit never changes. It stays. I think from the beginning of time, from Adam and Eve. We still have egos. We still are jealous. We still deal with developing character, trying to be a better person. That never changes.”

Given the sweeping changes across American society – and the world – throughout his career, Lieberman theorizes that girls and boys have been equally affected. One example, he said is “the advent of technology. A cell phone has become the greatest gift we have,” the rabbi said. “I can access music, Torah learning. It’s at my fingertips. Yet it also can be a most destructive instrument because I can ruin someone’s life in a second by spreading what they call fake news.“ One of the greatest life challenges for the teenagers he’s currently teaching is, “How do they engage in a good, proper way and not waste time by using it in a negative way? While the texts have remained constant, the question is, how do you take that text and put it both in their hearts and in their minds?’”

Fast Takes with Rabbi Lieberman

Jewish Journal: What Torah figure do you most admire?

Rabbi Lieberman: One is the Jewish philosopher Philo and then the son of Maimonides, Avraham ben ha-Rambam, a physician who led the Jewish community of Egypt. Oh, the empathy he had for his patients.

J.J.: What do you do to relax?

Rabbi Lieberman: (Gazing at the volumes high above him) Any one of these books.

J.J. Your favorite Jewish food?

Rabbi Lieberman: There’s nothing like it. My wife’s overnight potato kugel.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.