Is Israel good or bad? Are Jews good or bad? These are not rhetorical questions. For the average person who sees all the hatred directed at Jews and Israel on college campuses and around the world, it’s a natural question. After all, how good could Jews and Israel be if there’s so much hatred directed towards them?

People don’t usually hate good things; they usually hate bad things.

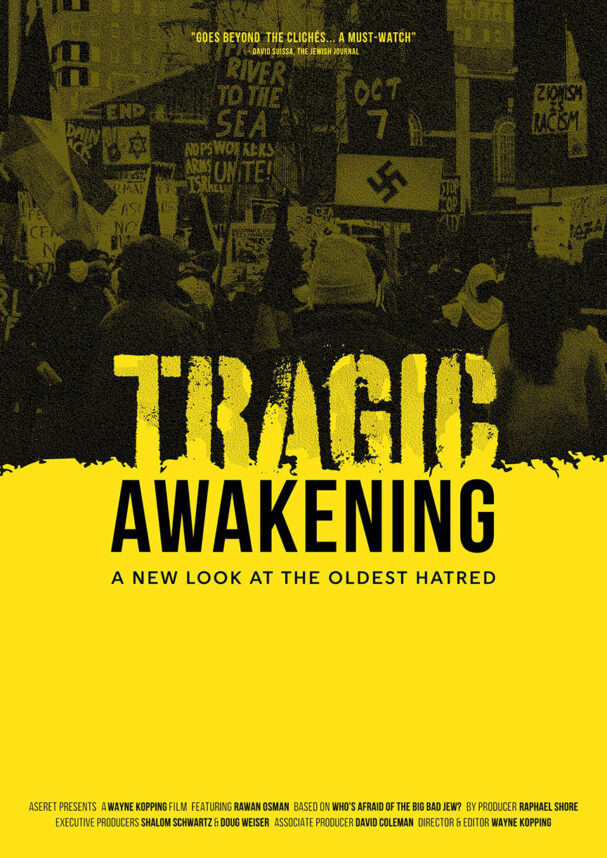

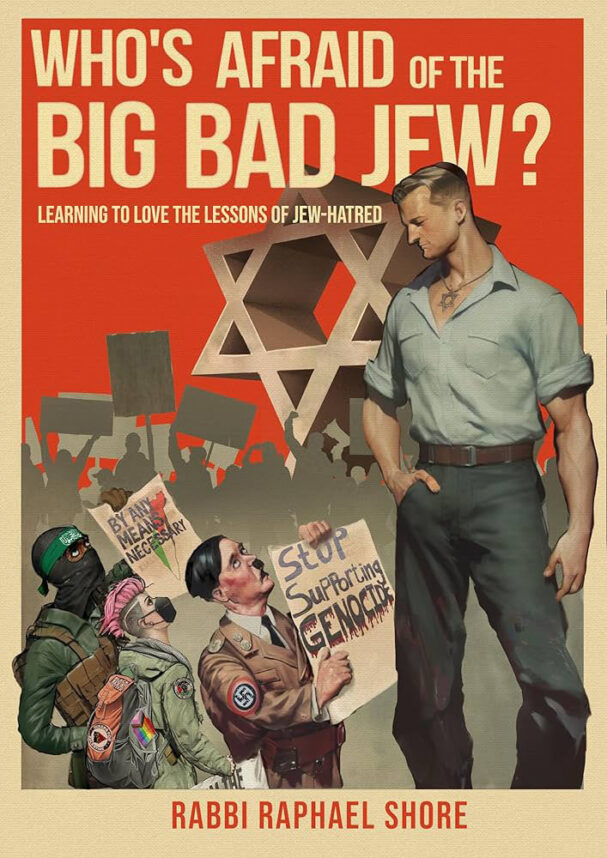

Which is why every Jew must see a new documentary titled, “Tragic Awakening: A New Look at the Oldest Hatred.” The film, produced by Raphael Shore in conjunction with his new book, “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Jew?”, advances an idea we may have heard before, but it does so in a fresh and provocative way that makes it uniquely relevant to our times.

Which is why every Jew must see a new documentary titled, “Tragic Awakening: A New Look at the Oldest Hatred.” The film, produced by Raphael Shore in conjunction with his new book, “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Jew?”, advances an idea we may have heard before, but it does so in a fresh and provocative way that makes it uniquely relevant to our times.

Jews are hated not because they are bad but because they are good. That, in a nutshell, is the premise of the film. But before it gets there, “Tragic Awakening” takes you on a 3,000-year journey that explores the roots of antisemitism through the eyes of an Arab Zionist, Rawan Osman.

“I grew up in Lebanon and I hated the Jews. I was told that the Jews are evil. That they hate everybody and they would do anything to achieve their goals,” Osman says at the beginning of the film. “In the media, in the news, in the newspaper, [they] sent the same message. The Jews are our enemies. I was told that the Holocaust was a lie.”

The film’s motif is a conversation between filmmaker Shore and Osman that revolves around the meta question: Why do people hate Jews?

“Rohan Osman is an Arab Zionist,” a narrator intones. “You don’t find that every day. Rohan was on a search. She was on a search for truth.”

In her twenties, Osman moved to France. “I revisited the narrative I was taught at school, by my parents, by my friends. And over time as I studied Judaism and studied the Jewish people that grew,” Osman says. “Reading this history changed my mind and I was angry. Because the Jew is not my enemy.”

Meanwhile, Shore shares with Osman his own journey of discovery.

“I began to study this topic [antisemitism] all the way back to my days in university. I wanted to try to figure out why. What is going on? How do we explain this phenomenon?” he asks.

“There are three possibilities. Either the Jews are just a rotten people, and in every generation there’s something else that’s rotten about them. That doesn’t make sense. We’re not really worse than China, or Iran, or Syria, or Russia.”

“Possibility number two is scapegoat. Antisemitism always denotes a society in deep trouble. And it happens when groups feel that their world is spinning out of control. And when the society becomes unhealthy, antisemitism is something that people reach for. So they’re looking for a scapegoat.”

The scapegoat explanation is familiar territory. The film buffets that argument with testimony from luminaries like Yossi Klein Halevi, the late Chief Rabbi Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, Bari Weiss and Douglas Murray.

“The Jews get condemned in one place for being rich and in another for being poor,” Murray says. “Condemned in one place for assimilating and in another for not assimilating. So you see how in the very same moment, the Jews are once targeted by neo Nazis, and they’re accused of being neo Nazis. It is always morphing.”

“Every single place that Jews have landed in the world, every different culture come up with different reasons why they hate the Jews,” Rabbi Sacks says. “It takes different forms in different ages. In the Middle Ages, Jews were hated for their religion. In the 19th and early 20th century, they were hated because of their race. Anti Semitism is a shape shifting conspiracy theory. The far right sees the Jews as the left. The far left sees the Jews as the right.”

Indeed the scapegoat argument is so true and plausible and easy to understand, in a certain sense, it’s also deadening. It feels like closure: They will always find reasons to hate us and blame us for everything, so all there is to do is be vigilant and fight back.

The power of the film is that it goes beyond those familiar arguments.

“I don’t think it’s merely scapegoating the Jews,” Shore says. “It is really something about the Jews… The third reason they hate us is because we’re Jewish. There’s something about Jews that they really hate.”

And who does he introduce to unpack that idea? None other than the ultimate Jew-hater himself, Hitler.

“The conventional wisdom is that Hitler was an irrational madman. I think that’s a mistake. He was certainly evil, but that doesn’t mean that he didn’t have compelling reasons to explain it,” Shore says.

“Hitler believed that there was one great conflict that drives human history, and that was the idea of survival of the fittest. It’s based in ideas of social Darwinism and Malthusianism. Hitler believed that just as in the animal kingdom, where ruthlessness and power governs the animal world, so also should it be for man.”

The Jews, with their ethics and life-driven ideals, represented a direct threat to Hitler’s Darwinian vision where the frail and the weak would be left behind.

“Hitler believed that if the ideas of humanitarianism, love, equality, democracy were to succeed, that would be the end of humanity,” Shore says in the film. “The ideology of social Darwinism argued that civilized societies were harming humanity by helping the poor, the sick, and those who nature would have killed off.”

This provocative framing of Jews as a threat is introduced about halfway into the film, and that’s when the film really takes off.

“How could this little, small, miserable, weak people without a state and without an army, how could they possibly be threatening the might of Nazi Germany?” Shore asks. “The answer is that you’re missing the point. The Jews weren’t a physical threat. Hitler never viewed the Jews as a physical threat.”

The Jews were “a spiritual and moral threat.”

Hitler looked at the world around him and saw that humanitarian values had won over the hearts and minds of most of western civilization, and wondered: Who’s responsible for this ideology that is so detrimental to human progress? Who’s responsible for bringing that into the world?

“Hitler correctly answers that it was the Jews. As he wrote in Mein Kampf, it’s always primarily the Jew who tries and succeeds in planting such mortally dangerous modes of thought in our people.”

In other words, the Nazi revolution was “a rebellion against what had become accepted as the ethical foundations of Western civilization, and those were Jewish ideas in their core.”

Western culture itself is rooted in the Hebrew Bible, as the film reminds us. “The values that we got from God, the value of life, peace, equal justice, proactive social responsibility, universal education, these all come from the Jewish people. Over the course of 2,000 years with the influence of Judaism, Judeo-Christian values, the world bought into these ideas.”

The film advances monotheism as the original basis for antisemitism, even connecting the Hebrew word Sinai with the Hebrew word for “hate.” It quotes a Talmudic passage to the effect that “hate” entered with the Ten Commandments, the eternal emblem of universal morality.

It would be wrong to shy away from these Jew-centric ideas because they smack of Jewish triumphalism. That’s not how they are portrayed in the film. Rather, they are seen primarily through the lens of Jew haters. That is where they get their credibility.

The film identifies something it calls astonishing: Hitler’s hatred for the Jews was actually “more fear than it was hate.” Hitler didn’t want to kill the Jews because they were bad; he wanted to kill them because they were good.

The rest of the film expands on that central idea, with a special focus on the state of Israel and the post Oct. 7 world. I won’t give it all away except to say that there’s more light than darkness as the film progresses, with Osman playing a crucial role in the narrative.

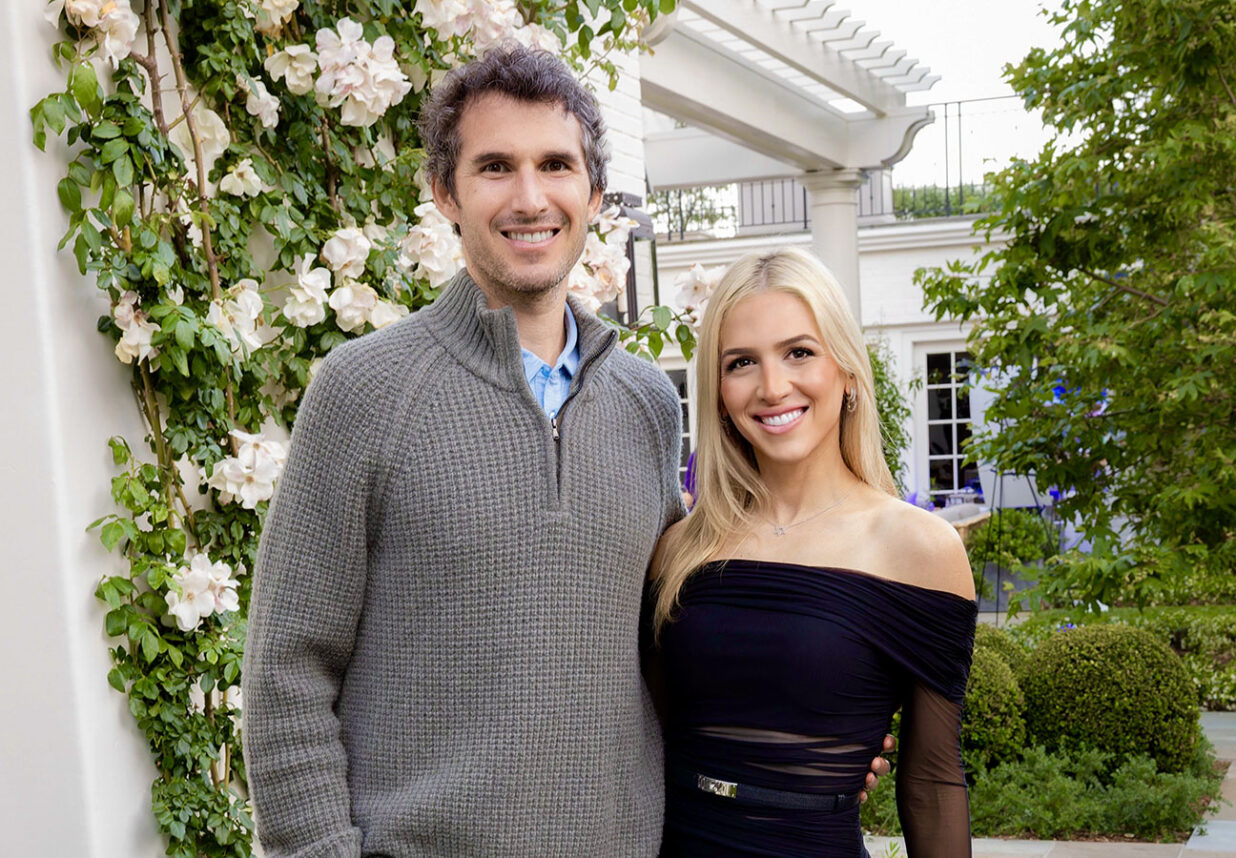

I saw the film Saturday night at a private home in Beverlywood. Shore was there to answer questions after the screening. With many parents of college students in the crowd, it was natural that the surge of antisemitism since Oct. 7 dominated the discussion. Jews are anxious these days, and for good reason. Our instinct is to fight back, also for good reason.

But by reframing Jew hatred, the film introduces a new way to educate and empower our community. This is especially relevant for all the Jewish kids who have been put on the defensive by the relentless assault on Jews and Israel on campuses and city streets. Reframing that hatred as “they hate us because we’re good” can be not just a psychological and morale booster, but also a call for Jews to keep working on ourselves.

This goes beyond the usual calls to build Jewish pride, which is necessary but not sufficient. What “Tragic Awakening” does is close the loop between Jewish pride and Jewish hatred.

Jew haters are not just hateful or hypocritical or evil. They hate Jews because of something deeper inside of Judaism, something connected to what Jews represent, to what Jews have brought to the world and especially to Western civilization. What nourishes Jewish pride is also what nourishes Jew hatred.

With all the flaws and blunders of an imperfect Israel, that principle holds for the Jewish state as well. The Western values that Israel brought to a region dominated by dictatorships and theocracies were a threat to those regimes. They needed to destroy Israel not because it was bad but because it was good.

As Shore said during the discussion, at the very least he hopes the film will start a conversation. Finding goodness in the Jews and in Jewish ideas at a time when much of the world is coming down on us is not a bad way to start.