Shavu’ot 2023

The Ten Commandments are not the Ten Commandments

I’ll start my thought on Shav’uot with a bit of “Adult Education” and then to a thought that addresses the inner life.

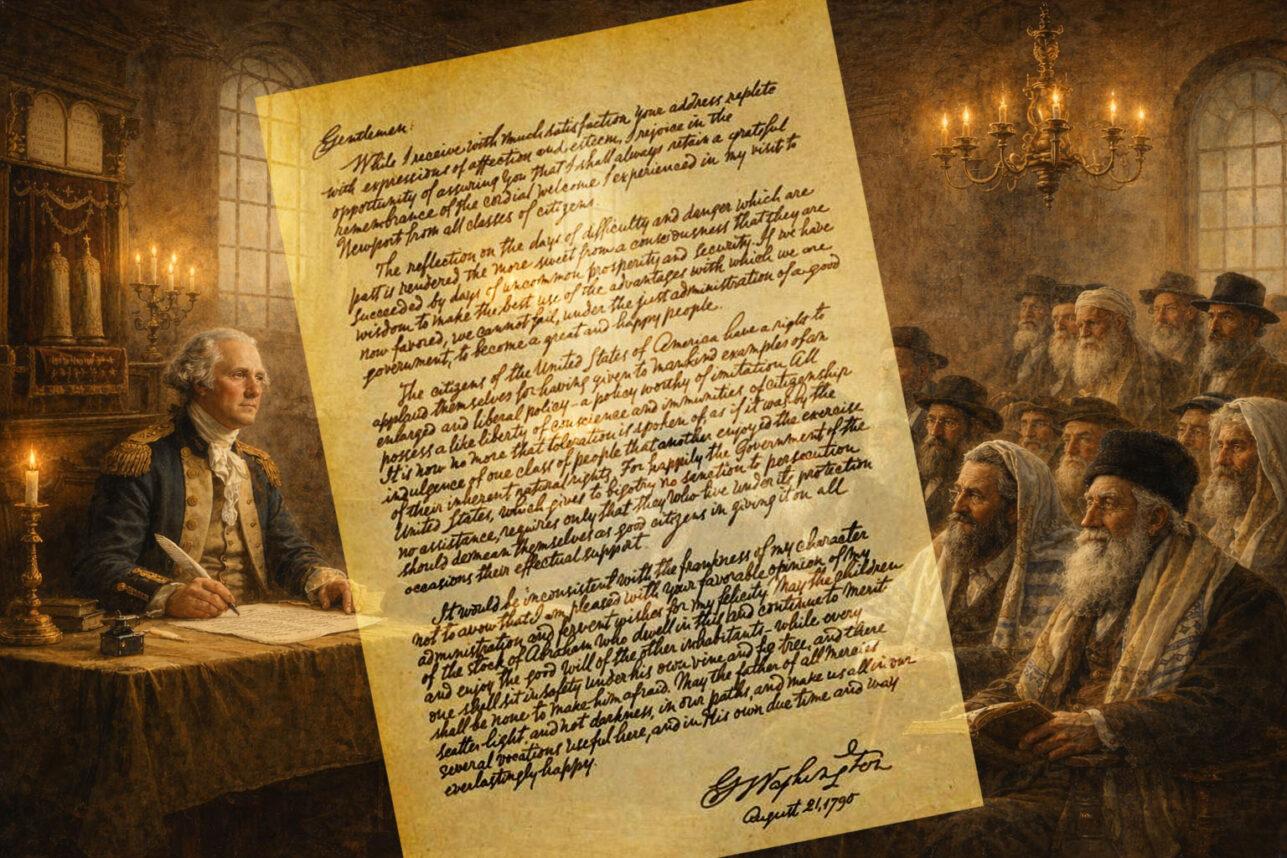

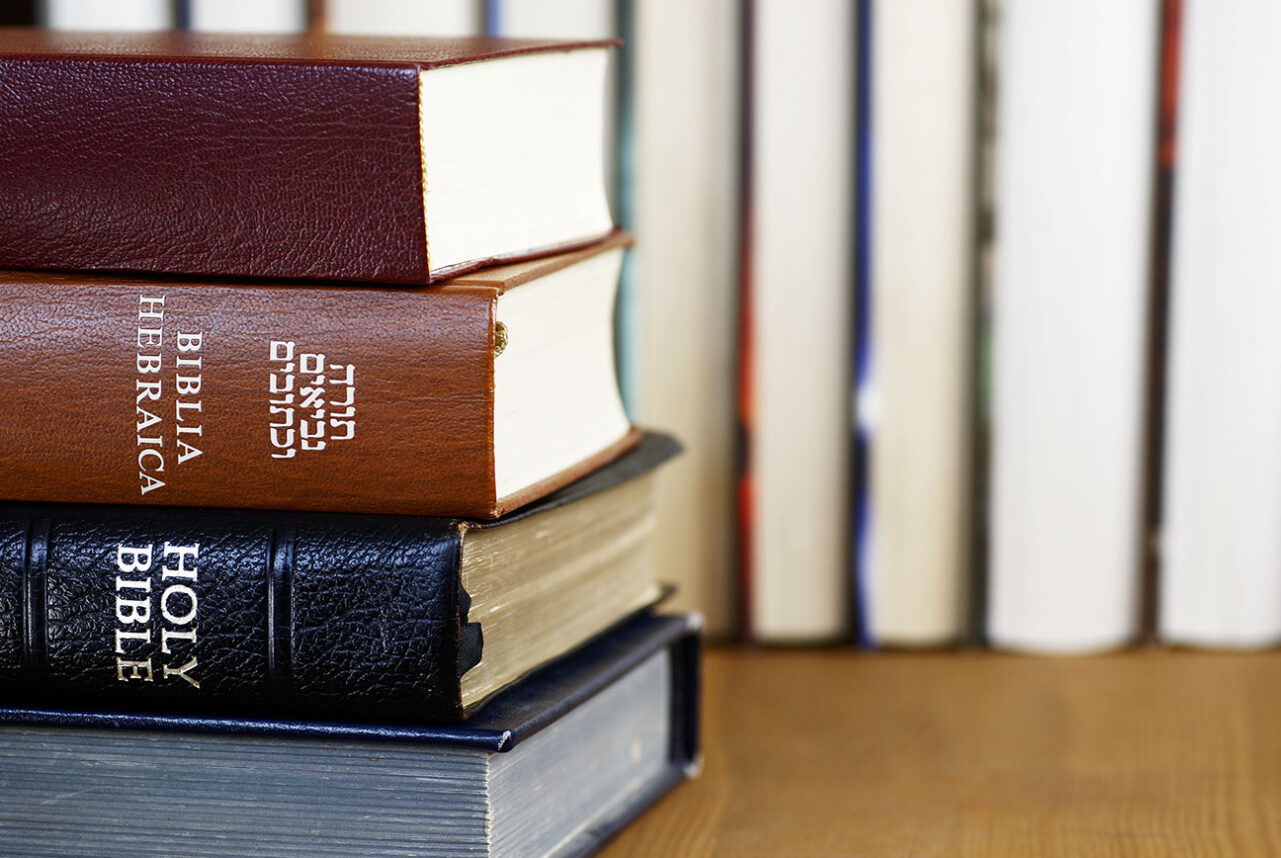

Here is something you probably didn’t know. The term “Ten Commandments” – “aseret ha-mitzvot” – does not occur in the Bible. Nowhere. Whenever you see the term “Ten Commandments” in English, for example in Exodus 34:28, we are reading an attempt to translate “aseret ha-d’varim.” “Aseret ha’dvarim” means literally the “Ten Things,” the “Ten Matters,” or the “Ten Words.” “D’varim” does not mean “commandments.” The Hebrew word “davar” is not translatable into one word in English.

Ever since the time of ancient rabbis, the “ten d’varim” has been called “aseret ha-dibrot,” The “ten dibrot.” The term “dibrot,” plural of “dibbur,” also cannot be translated into one word of English. The Hebrew term “dibbur” connotes “divine utterance,” or “speech act of God.” The best way, in my opinion, to translate “aseret ha-dibrot” is “The Ten Speech Utterances of God” (most Bible scholars go this way). I know. Not very catchy.

The Septuagint (third-second BCE Greek translation of the Bible) and the Vulgate (the fourth century CE Latin translation) had it much easier. They translated the “aseret ha-d’varim” as the “dekalogos,” or “decalogue,” as we spell the word in English. The Greek and Latin term “logos” come very close to the range of meaning of both “davar” and “dibbur.” Logos can mean “word,” but also “the word of God.” “Logos” can mean the study or theory of something, as in “psychology” – the “study of the soul.” In Stoic philosophy, “Logos” can mean “the mind of God.”

“Decalogue” in Exodus 34:28 came into English as “ten verses” in the Tyndale translation, the earliest English translation of the Bible. “Commandments” was used in the Geneva Bible to translate aseret ha-d’varim, the next oldest translation, and the King James version followed suit. “Ten Commandments” has been in the English language ever since.

In my opinion, if we are going to refer to the Hebrew term “aseret ha-d’varim” in English, it would be ideal to say “Decalogue,” but I think Hollywood nixed that possibility. I can’t even imagine the Charlton Heston movie being called “The Decalogue!” If we wanted to be precise, we would say, “the Ten Commandments, called ‘aseret ha-dibrot’ in Hebrew.” That does sound a bit pedantic, so we will just use “the Ten Commandments” but at least we will know the rest of the story.

The question remains: why did the ancient rabbis prefer “dibbur” as the word of God, (plural “dibrot”) to davar? Most scholars agree that “davar” became “dibbur” because of the influence of Aramaic. The Hebrew “davar” likely became “dibura” in Aramaic, and gained a special connotation, like the Greek “logos.” “Dibbura,” and its synonym in Aramaic, “memra” both refer to an act of divine revelation, a moment of prophecy, even if a minor one. The ancient rabbis, who thought in both Hebrew and Aramaic, back-translated “dibbura” into “dibbur,” and used the Hebrew “aseret” (from the Hebrew word “eser,” ten).

Another reason not to call the Decalogue “commandments,” a reason you have doubtless heard often, is that the first “commandment” is not a “command” at all. The first dibbur is “I am Adonai your God who took you out of the land Egypt the house of bondage.” This verse is not even a revelation, per se. The listeners had just been through the Exodus from Egypt. Why would this statement of the obvious be a “dibbur?”

Some facts are more than facts. Stating a fact with emphasis is to state the fact, plus something else.

And rules are more than rules.

Think of it this way. We know rules of conduct, “thou shalt” and “thou shalt not.” People often say, “I know I shouldn’t have done that,” right before they tell me something they did. What if an angel God appeared to that rule-breaker at that very moment, as an angel appeared to Abraham just before he was going to slice Isaac’s throat. Right before someone is fixing to get into a stupid argument over a petty thing, a fiery angel of God appears to them and says, “Don’t do it.” A rule is one thing. A flaming seraph is another.

Certainly, we can’t live like that: every commandment backed up by a searing angel, the voice of God reaching from the soul of the universe into the depths of your soul. The rabbis wanted to tell us that these particular words of the Ten Commandments are “dibbur,” bearers of special divine urgency. Each element of the Decalogue carries within it a world of meaning, a world of moral instruction. For example, “Don’t steal” includes wasting someone else’s very limited supply of time. “Don’t murder” includes harsh language and gossip.

Imagine that each of the so-called “Ten Commandments” is the tip of vast pyramid of meaning. Imagine that we Israelites go from building pyramids as mausoleums to constructing pyramids of meaning, standing pristine, rooted in our souls and peaking in how we conduct ourselves. Some norms are rules. Some rules are commandments. Some commandments are revelations of God’s presence.