Preface for Sep 9, 2022:

Dear Friends,

This Shabbat, Ki Teitzei, is the fifth of the seven Sabbaths leading from the 9th of Av to Rosh HaShanah, Yom HaDin – the Day of Judgment. Yes, the Day of Judgment is coming; are you prepared?

One of people’s resistances to the High Holy Days is this idea of judgment. People say, “I don’t like to feel judged.” The bad news is we are judged anyway, by others, by ourselves, and perhaps even by God. I think what people mean is that they don’t want to be judged unfairly, or in a harsh manner. The good news is that judgment, ideally, ought to be the first of a two-step process.

Our judgments should be reasonable and fair, and holding others (and ourselves) to account should be with an eye toward the second step – transformation and reconciliation, as much as possible. Reconciliation might include forgiveness and restoration, but at least we let go of judgmentalism and anger.

This is a deep thing: to judge yourself honestly and fairly, as a part of self-love and healing. As the inner life tradition teaches us, we can’t heal until we confront our brokenness. The brokenness is where the light gets in.

We will continue to use our Friday night and Shabbat morning services for “preparing the heart for the Days of Awe.” We will keep alive our discussion of the Shofar, the idea of the Day of Judgment (and difficult liturgy in general), The Divine, Repentance, Teshuva, Attempted Filicide, Angels, Confession and all things Days of Awe related.

I will be reading from Leonard Cohen’s Book of Mercy, # 1

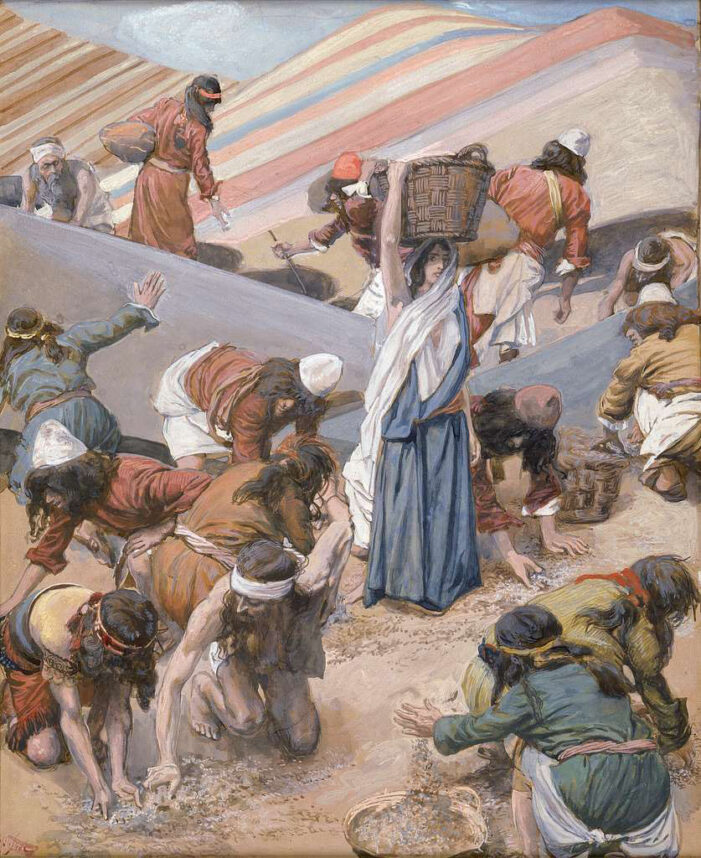

Selection from Torah Portion Ki Teitzei:

Deuteronomy 24:17-22

Selection of the Fifth Haftarah of Consolation, Is. 54:1-10

Isaiah 54:1-5

The Shadow Side

Thoughts on Torah Portion Ki Teitzei 2022, adapted from previous versions

Last week, my Shabbat thought on Torah portion Shoftim focused on the shadow of the law. By this term, I mean that in addition to looking at the contents of different teachings, commandments, statutes and laws, we ought to be inferring the background in which these statements are rooted.

For example, the great charge we are given in last week’s Torah portion, “Justice, justice shall you pursue!” is likely rooted in a time where injustice was rampant. Laws against bribing judges would only make sense in a time where bribery of judges was a concern. Each law is rooted in an unseen background, in a shadow.

My guiding theme is that the laws in these two Torah portions, Shoftim last week and Ki Tetzei this week, as righteous and even beautiful as many of these laws are, indicate a culture and a society in crisis. These laws range from establishing order against disorder all the way to fighting the entropy of things falling apart.

The idea that laws exist in a background is finely articulated in Robert Cover’s 1982 essay, “Nomos and Narrative” (found in many places on the web). For the non-expert, this article can be daunting. His main point is that the world of law, “nomos,” exists within some social construction of reality, a “narrative.” The most well-known example of this idea is the statement in our Declaration of Independence, which I paraphrase thus:

It is an obvious truth that our Creator has endowed every human being with rights that are not granted by the state and cannot be taken away by the state. One of the main purposes of the state is to protect these rights, especially the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of well-being.

Why might we call this classic articulation of the foundation of the liberal state a “narrative?” It is a narrative in the sense of a myth, not meaning a fable, but rather a narrative containing words as symbols, pointing to deep, inexhaustible meanings that orient our lives.

The terms included in this world view (as I have paraphrased Jefferson) cannot be defined to the satisfaction of a skeptic, but we all know at least roughly what these words mean. These key words are known in the soul, the source of our deepest value systems. Word such as “truth,” “Creator,” “endowed,” “human being,” “rights,” “life,” “liberty,” and “well-being” symbolize the depths of our experiences and visions as human beings and orient some of the foundations of the moral reality in which we live.

The laws, norms and values expressed in our Torah portions indicate a moral reality in the background, but the meaning of that moral reality is always under dispute. Part of our polarization and culture wars today is concerned with people disputing our nomos, our shared moral reality. Proponents of different views aim to assert their nomos above all others. That is exactly how it is supposed to be in a free country – a free market of ideas. The question is: how do we present our ideas to others? With hatred and venom, which lead to polarization, or with reason and clarity and some measure of truth.

From the perspective of a liberal society (and Jewish ethics), the worst kind of nomos is one in which things can’t even be discussed, where people get “cancelled” when their views (or humor) go against the grain. The reason we have a right to free speech is because there’s always somebody who wants to shut down our speech. A free society requires the free exchange of ideas, as our individual and shared inner worlds develop.

Put simply, when we study the idea of “nomos and narrative,” we are invited into the deep discussion of the meaning of law, especially the moral law, in the symbolic world in which the law exists. This idea may be applied directly to each of our lives. We all live in a “nomos,” a world of values, norms and behavioral rules. We typically don’t reflect on or philosophize about our inner nomos very much. What we think is right or wrong, what we think our moral obligations are, what the obligations of others are, is unconsciously guided by our inner nomos. Unless we philosophize or reflect, we only become aware of this moral reality when we believe that someone else has violated our nomos, or when someone is trying to force their nomos upon us, as opposed to reasoning with us.

In addition, an enlightened person is, minimally, one who realizes that their own thoughts, feelings, speech and behavior are not always aligned with their own values.

We realize that just as all law has a shadow side, we also have within us an inner world that contains a shadow self. This shadow self, at least partly, exists in direct opposition to our conscious nomos. When people are open to discussion, they sometimes realize that they are a walking thicket of contradictions. Most of us can regulate that oppositional world, consciously or by habit. Until we can’t.

Hence our Torah portions – norms and moral crises, law and disorder, crime and punishment, entropy and the moral commitment to make the center hold.

Hence also Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Rosh Hashanah ought to be a deep meditation on our world of values, norms and behaviors and then a resulting moral commitment to uphold that world. We then spend 10 days meditating on that nomos and our own tendency to live contrary to it. Yom Kippur is the day when we squarely face the shadow, the contrary self.

Will we own up to the moments when we break bad from our values, and will we do whatever it takes to bring our destructiveness under control?

The shadow thinks it knows. We have to know better than the shadow.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.