“Pilagá Woman With Her Kids,” Las Lomitas, Formosa, by Grete Stern (1964). © Estate of Grete Stern courtesy Galería Jorge Mara – La Ruche, Buenos Aires, 2016

“Pilagá Woman With Her Kids,” Las Lomitas, Formosa, by Grete Stern (1964). © Estate of Grete Stern courtesy Galería Jorge Mara – La Ruche, Buenos Aires, 2016 During her long life, Grete Stern was recognized as an influential force in 20th century photography, not just in Argentina — where she lived for 64 years — but also internationally. She was founding director of the photography section of the Argentine Museum of Fine Arts, and her ideas and techniques helped shape several generations of South American photographers. Her work has been exhibited in many museums, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art, a 2015 show that received a glowing review in The New Yorker.

Stern (1904-99) was born in Germany and educated at the Bauhaus, the legendary German art institute that flourished between the world wars. Aware of the danger she faced as a Jew in Europe, she immigrated to Argentina in 1935. Once there, Stern didn’t wait long to make her mark. Two months after arriving, she exhibited her groundbreaking photos at the offices of a magazine whose art critic wrote that Stern had established photography as a genuine art form in Argentina.

Stern is perhaps the most prominent among the Argentine-Jewish photographers whose work is included in an exhibit opening Sept. 16 at The Getty Center — “Photography in Argentina, 1850-2010: Contradiction and Continuity.” It’s a massive show, comprising nearly 300 photographs by 60 Argentine artists, from the dawn of photography to contemporary work.

Two of the show’s sections, “Civilization and Barbarism” and “National Myths,” explore the gap between Buenos Aires, a city with handsome buildings and a population largely of European background, and the provinces, with their poorer and much larger indigenous population. The first two parts of the exhibit also delve into the contrast between Argentines’ iconic self-images — the gaucho, Evita and Buenos Aires as the sophisticated Paris of the Southern Hemisphere — and the realities behind their myths.

A third section, “Aesthetic and Political Gestures,” shows photographers’ responses to the turbulent second half of the 20th century, which included a Dirty War during which more than 30,000 people were “disappeared” — killed — by a military junta, as well as periodic blips of economic and political turmoil.

A fourth part, “New Democracy to Present Day,” deals with the period after the restoration of democracy in 1983 and how the works of Argentine photographers have been at least as cutting-edge as the creations from artistically related movements in Europe and North America.

Two other Jewish photographers in the exhibit, Jaime Davidovich and Osvaldo Romberg, were at the forefront of these avant-garde trends.

Judith Keller, senior curator of photographs at the Getty Museum and co-curator of the Argentine photography exhibit, said that Romberg and Davidovich “came out of the 1960s movement of conceptual art.” Conceptual photography is when a picture is built or posed to give visual form to an idea or concept. “The purpose of using photography this way is to point out aspects of life that are normally ignored or considered too mundane for art,” she said.

Keller said that Davidovich, who died last year at 79, was well-known for his experimental work in video, film and TV. “We hope that by exhibiting some of his photographic work, he will become better known for his photography,” she said. “He was commissioned fairly often in the 1970s to do installation art, which was becoming a new practice at that time. … What we’re exhibiting in our show are … black-and-white images of these installations.”

Davidovich’s photos are of typical sidewalks, but with white adhesive tape placed on them to create a cityscape different from what we normally see, thus challenging the viewer to look at everyday scenes as artistic installations.

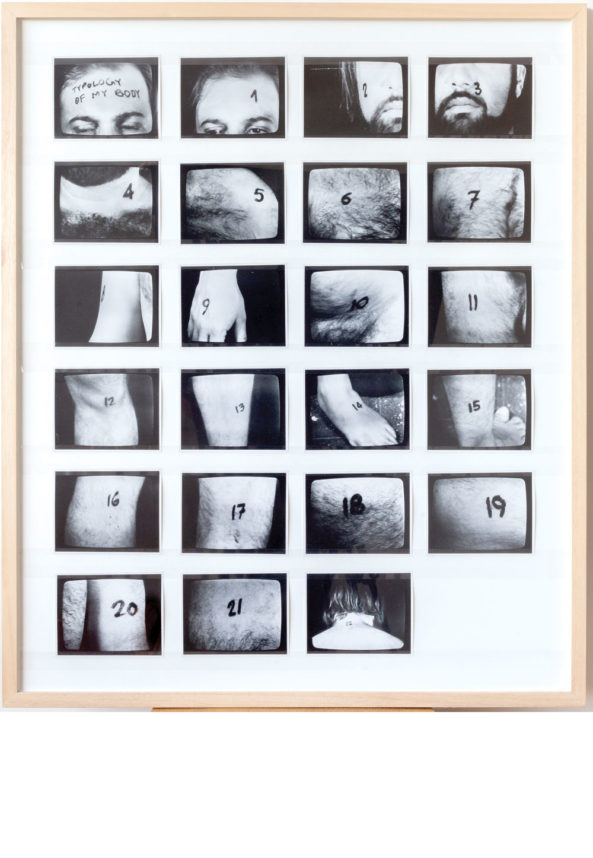

In contrast, Romberg, still artistically active at 79, creates multiple images of himself — bearded, paunchy, decidedly not a model — that ask us to look at a normal human body in a matter-of-fact manner.

Each of Romberg’s works in the exhibition consists of anywhere from three to 20 or more small photos, each showing an individual body part (neck, foot, elbow, etc.) marked with a large black number. By deconstructing the body into separate elements, the presentation smacks of a forensic display, or perhaps an odd jigsaw puzzle whose parts make a whole human.

Jews first immigrated to Argentina in the late 19th century and at first many lived and worked on farming colonies far from Buenos Aires. The old joke among Argentine Jews was that those colonists planted corn and soybeans but harvested doctors and lawyers. While there is some truth in that, subsequent generations of Argentine Jews — whether descended from farm colonists or later arrivals — have also yielded large crops of artists, writers, actors, musicians, dancers and filmmakers who have made impressive contributions to the vigorous Argentine arts scene.

Asked if any works in the show directly reflected Jewish life in Argentina, Idurre Alonso, associate curator of Latin American collections at the Getty Research Institute and the show’s co-curator, mentioned one in particular: “At the beginning of the show, the early photos, when we’re addressing the role of immigration, there’s one late 19th- or early 20th-century photo that portrays a Jewish family. That, I think, is the only clear reference to that in the show.”

“For the most part,” she said, “Argentine Jews are so blended in the community that I don’t think you can say about any of the Jewish photographers that their work in this show focuses on their being Jewish. Their work contributed to whatever artistic movement they were a part of.”

That blending-in was certainly the case with Davidovich and Romberg. And even though Stern went to Argentina to get away from the Nazis, the content of her art is not overtly Jewish either.

Stern’s life, it should be noted, had its share of pain. Her son committed suicide when he was 25; her daughter left Argentina during the Dirty War in the 1970s; and Stern herself suffered from lifelong depression. Yet, through it all she continued to produce an enormous amount of work, and was a mentor and inspiration for Argentina’s creative community for more than 60 years.

Stern’s photos in the Getty exhibit are not the surrealistic, subversively feminist photomontages of the New York MoMA exhibit, but rather the extremely moving documentary photos she took in the 1960s of indigenous people living in the Argentine countryside, far from Buenos Aires. With Stern’s ability to catch a fleeting moment that’s unassuming yet iconic, her subjects look quietly dignified as they go about their grueling, hard-scrabble lives.

Given the political madness and family tragedies she lived through, and the struggles she faced in establishing herself — as a Jew, an immigrant and a woman — quiet dignity is an attitude with which Stern probably identified.

“Photography in Argentina, 1850-2010: Contradiction and Continuity” runs from Sept. 16 to Jan. 28. It is part of the communitywide Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, an exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Southern California, organized and funded by the Getty Foundation.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.