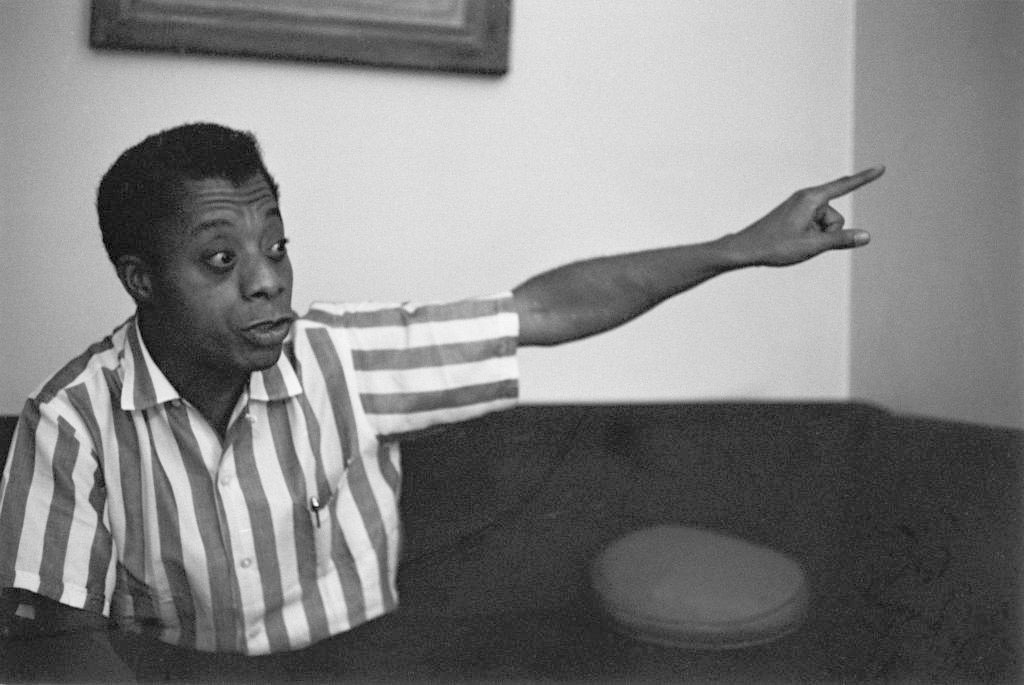

“You can only be destroyed if you feel that you can be labelled by the most outrageous n-word,”

is a PC version of a statement by James Baldwin that Chris Rock on Martin Luther Day omitted

because political correctness determines that they should not literally be heard,

even when declared by someone who is dark-skinned and, unlike objectors, not dim-witted.

Relationships with other people basically depend on how they are by us defined,

not literally but mentally, in language of the state in which we live, which is our state of mind,

a state determining as well not always well, how people judge you if you’re Jewish,

the state to which we all pledge our allegiance, while regarding all its rules as more than merely trueish.

In “James Baldwin & the Fear of a Nation,” NYR, 5/12/16, Nathaniel Rich, writes:

No one has done more to popularize Baldwin in recent years than Ta-Nehisi Coates, who used Baldwin’s address to his nephew in “My Dungeon Shook,” the first part of The Fire Next Time, as a model for Between the World and Me, the most widely read book on race in America in a generation.2 Consecutive short essays by Coates in The Atlantic about his response to Baldwin’s nonfiction demonstrate the difficulty in pinning Baldwin down. “Baldwin’s writing is roughly contemporaneous with the Civil Rights movement, but he seems to share none of its hope, none of its belief in the power of love to conquer all,” Coates wrote in the first essay. Writing two days later: “My point is that after all of this—after all his hard talk—Baldwin is still talking about love.”

This year on January 18, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the most-viewed speech in America was Chris Rock’s recitation of “My Dungeon Shook.” Delivered at Harlem’s Riverside Church, about a mile west of Baldwin’s childhood neighborhood, the performance was remarkable both for Rock’s impassioned delivery and his omission of the essay’s most incendiary passage: “You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger.” There remain limits to what even a figure as respected and outspoken as Rock can say about race in America today.

In “Blues for Mister Charlie,” Anna Venarchik writes in the NYT, 7/29/24:

How do people come to know themselves? One way is by reading fiction. The profound act of empathy demanded by a novel, forcing the reader to suspend disbelief and embody a stranger’s skin, prompts reflection and self-questioning. But most people don’t read novels. In his essays and public speeches, Baldwin tried to create a similar effect through allegory and metaphor. At times he reduces the nation to the size of an individual (speaking, for instance, of the American “state of mind”); elsewhere he elevates the individual to the level of an entire race. Baldwin went so far as to suggest that the racial anxieties of white America derive from the most primal, universal fear of all: fear of death. “White Americans do not believe in death,” he writes in The Fire Next Time, “and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them.” It is difficult to take this literally—it requires, first of all, that you accept his claim that black people have no fear of death—but as metaphor it stands to reason that confronting the subject of racial iniquity requires questioning one’s most basic assumptions about the workings of American democracy. Can a system of representation be said to be successful when equal representation is denied to so many? …..

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.