Pope Benedict XVI’s visit to a German synagogue was replete with symbolism: most notably, the potential for positive relations between the country’s Jewish community and a pope who served in the German army during World War II.

For Germany’s Jewish community, which has tripled to more than 100,000 since 1989 with the arrival of former Soviet Jews, the live broadcast of Benedict’s visit during World Youth Day in Germany served another purpose.

Millions of Germans tuning in to ARD-TV last Friday had a chance to look inside a German synagogue and hear an introduction to Judaism from a Cologne Jewish community board member, Michael Rado, as they waited for the pope to arrive.

They learned that Cologne is home to Germany’s oldest Jewish community, with documents dating back to the fourth century. They heard that this synagogue was rebuilt in 1959, on the site where a synagogue erected in 1899 was destroyed during Kristallnacht on Nov. 9, 1938.

Then they witnessed the rabbi’s warm welcome of Benedict, the moment of silence in which they remembered the victims of the Holocaust and the procession to the bimah as a choir sang “Heveinu Shalom Aleichem.”

For the Catholic Church, the public-relations value against the backdrop of simmering anti-Semitism and Islamophobia in Europe could not be underestimated.

But it could have been much different. While many Germans were proud when their cardinal, Joseph Ratzinger, was elected pope in April — the popular Bild Zeitung tabloid bore the headline, “We Are Pope!” — for many Jews, Ratzinger embodied a Catholic conservatism that sees other faiths as secondary.

Add to that the new pope’s boyhood membership in the Hitler Youth and his recent failure to condemn terrorism against Israel, and the possibility for tension was there.

For now, however, skepticism seems to have waned as the pope’s visit marks more evidence of his commitment to interfaith relations.

The event was a historic first: Never before had a pope officially visited a German synagogue. In fact, this was only the second time a pope has formally entered a Jewish house of worship; the late Pope John Paul II visited the Great Synagogue of Rome in April 1986.

Some said the presence of Israeli Ambassador Shimon Stein might bode well for relations between the Vatican and Israel, strained over Benedict’s recent failure to condemn terrorism against the Jewish state.

Others demanded that the pope follow words with deeds by opening the doors to the Vatican’s World War II-era archive, shedding light on the Church’s wartime stance toward the Holocaust.

In his remarks to some 500 people gathered in the Cologne Synagogue, the pope stressed the future, not the past.

Worried about growing anti-Semitism and xenophobia in Europe, determined to teach tolerance to Catholic youth and noting the negative role played by the Church in the past, Benedict declared his commitment to cooperation with Jews.

He added that interfaith dialogue must be carried out in recognition of “existing differences.”

“In those areas in which, due to our profound convictions in faith, we diverge, and indeed precisely in those areas, we need to show respect and love for one another,” the pope said to a standing ovation.

Some said afterward that the pope should have mentioned Israel, as well as the specific crimes of the church, such as the massacres carried out during the papally approved Crusades of the 11th-13th centuries and the brutalities of the Spanish Inquisition.

But Cologne Rabbi Natanael Teitelbaum said he is “happy with the pope’s remarks. He looked back on Jewish history, and said he is against terrorism and for mutual respect, and those are the most important things.”

Teitelbaum’s address also drew a standing ovation.

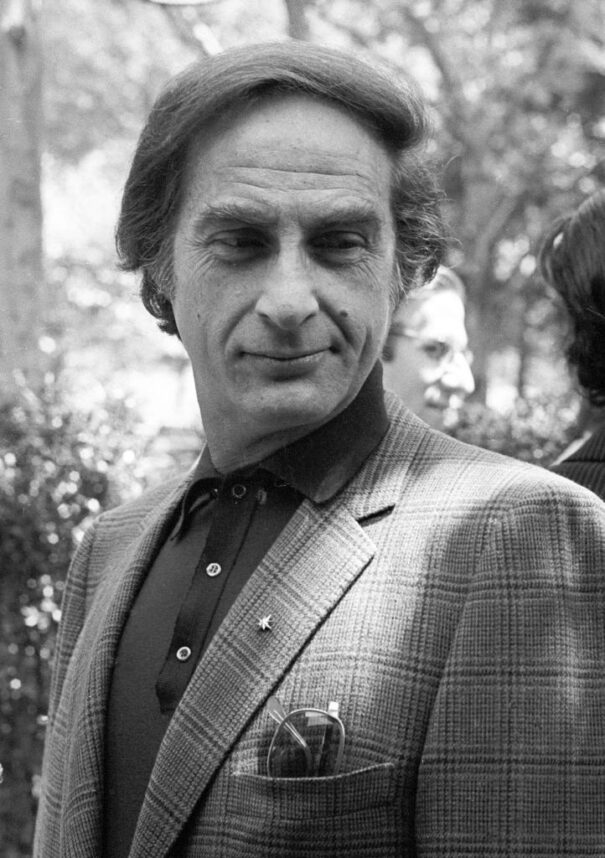

Paul Spiegel, head of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, said it did not matter that the pope did not directly address the subject of terrorism against Israel.

“That will be between the Vatican and the Israeli government,” said Spiegel, who survived the Holocaust in hiding and came back to Germany as a boy with his parents.

“My heart is full of the impressions of today,” Spiegel added at a news conference. “We are well on the way to mutual respect and, as the pope said, to mutual love.”

After the ceremony, guests — including local and national politicians, religious leaders and members of the Cologne Jewish community — personally greeted the pope on the bimah, shook his hand and presented gifts, including a large shofar.

There also were other types of gifts. George Ban, executive vice president and CEO of the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation, gave the pope a brochure about the work of his foundation, which supports Jewish education in Central and Eastern Europe.

“I don’t think it is very often that one has the chance to have your organization known by the No. 1 person in the Christian world,” Ban said.

Some guests came away with a souvenir, too: The royal-blue yarmulkes printed for the occasion with the date and the words “Besuch-Papst Benedikt XVI” — “Visit of Pope Benedict XVI.”