After four years of construction, the Jewish Quarter’s landmark Hurva Synagogue – built by Polish Jews in 1701, destroyed by Arab creditors two decades later, rebuilt in 1864 by followers of the Vilna Gaon, and dynamited in 1948 by Jordan’s Arab Legion – is being re-dedicated this Sunday and Monday (March 15-16, 2010). All the rest is commentary.

During a media tour this week, a beaming Nissim Arazi, who since 2003 has served as the CEO of the Company for the Reconstruction and Development of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem Ltd. (the JQDC), showed off the venerable if controversial NIS 43 million project which has been his dream for nearly a decade.

Arazi follows a distinguished list of public servants, starting in 1969 with then Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, who have served as either chairman or director of the government agency charged with rebuilding the Old City’s Jewish Quarter. That historic job had largely been completed when Arazi stepped onto the scene. But the new CEO resisted calls for the JQDC to be disbanded as redundant, instead pressing ahead with the Hurva project and protecting his fiefdom. (In Jerusalem, Nov. 2, 2007)

As the Hurva’s construction crane was being taken down, Arazi launched into the synagogue’s convoluted story, hailing the many figures responsible for the rebuilding. In 1999, he explained, a public committee was formed by then Minister of Housing, Rabbi Yitzhak Levi and headed by Rabbi Simha Hacohen Kook with the intention of recreating the building whose famous dome once dominated the skyline of the Jewish Quarter.

Levi and Rabbi Kook ultimately prevailed, ending a protracted architectural argument about whether to build a new and modern synagogue or to symbolically copy a building which had been the center of cultural and spiritual life in Israel and the Jewish Quarter in the second half of the 19th Century and first half of the 20th. Ultimately, architect Nahum Meltzer’s plan was adopted to faithfully reconstruct the quadrangular synagogue with its central dome designed by Ottoman court builder Assad Effendi, incorporating the extent ruins and making adjustments for today’s building code.

Among those Arazi thanked were: Dov Kalmanovitch, then chairman of JQDC’s board; Yinon Ahiman, the company’s CEO; Minister of Housing Natan Sharansky and his successors Ministers Effy Etham, Tzipi Livni and Ze’ev Boim; MKs Yitzhak Herzog and Meir Shitrith; Jerusalem’s two previous mayors Ehud Olmert and Uri Lopliansky; and deputy mayor Rabbi Yehoshua Pollack.

Before construction could begin, Arazi noted, the Israel Antiquities Authority conducted a thorough survey of the site. That dig, directed by archaeologists Hillel Geva and Oren Gutfeld, exposed findings dating back to the First Temple period and three plastered ritual baths from the time of Herod. The most significant discovery was an intact Byzantine arch standing along the remnant of a stone-paved street leading off from the Cardo. The arch – 3.7-meters wide, 1.3-meters thick and five-meters high – is preserved in the basement of the Hurva.

The archaeologists also found a small weapons “slick” from the riots of 1936, seemingly forgotten by the outgunned defenders of the Jewish Quarter during the 1948 War of Independence.

Moving indoors and dodging construction workers and porters delivering the pews, Arazi discussed the furnishings, stained glass windows and wall paintings. (At the time of the tour the chandeliers, Torah ark cover and other furnishings had yet to be installed.) The two-storey high Torah ark is a faithful copy of the original that was carved in Ukraine, he explained. In another layer of symbolism, Arazi noted that Ukrainian oligarch Vadim Rabinovich was one of the key donors of the new synagogue.

Selecting an interior design was problematic since the Hurva had undergone various renovations over the decades, Arazi noted. According to B&W and color photos unearthed by Israel Antiquities Authority restoration expert Faina Milstein, there were three stages in the decoration and painting of the prayer hall, each “correcting” the previous – from 1864 until the 1920s, from the 20’s to the early 1940s, and from 1940-41 until the synagogue’s destruction in May 1948.

Meltzer prevailed over Arazi and his steering committee to select a minimalist approach sensitive to Assad Effendi’s original design – thus visually emphasizing the Holy Ark and pulpit, as well as the remaining non-plastered masonry walls still standing after the building was blown up. Pointing to the relatively small women’s gallery upstairs, Arazi noted that stepped platforms were added in the new building where none had originally existed so as to maximize worshippers’ view.

Under the barrel dome Arazi opted, based on the spirit of the past paintings, to depict holy cities and sites in Israel. Jerusalem is symbolized by the Tower of David; Bethlehem by Rachel’s Tomb; Tiberias by a view of the Sea of Galilee; and Hebron by the Cave of the Patriarchs. Above the main door is a painting depicting Psalm 137:1 “By the waters of Babylon there we sat down and wept when we remembered Zion.” Artist Yael Kilmenik’s designs, none of which include human figures, allude to the romantic style of Bezalel founder Boris Schatz.

Turning to discuss the operation of the rebuilt Hurva, Arazi was on shakier ground. Though built by the JQDC in accordance with the decision of the Israeli government, the synagogue will be jointly operated by the Company and the Western Wall Heritage Foundation now headed by Rabbi Shmuel Rabinovich.

That decision reflects the process whereby the Jewish Quarter – intended for both secular and Zionist Orthodox Jerusalemites – has over the decades become predominantly ultra-Orthodox. Indeed three years ago, when the concrete was still being poured for the Hurva, Rehovot’s chief rabbi Simcha Hacohen Kook was already appointed as a rabbi for the synagogue. Kook, who is considered close to the ultra-Orthodox non-Hassidic leader Rabbi Yosef Elyashiv, was chosen by a panel of rabbis, with the blessing of Sephardic Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar.

Arazi, who said he was surprised by the rabbi’s appointment, refused to attend Rabbi Kook’s investiture ceremony.

Arazi himself may be forced to limiting his involvement at the Hurva to praying there. He will be replaced soon, along with five out of the eight JQDC board members. By statutory law, the new board members are to be chosen by the Housing Minister – and Ariel Atias is a Shas party stalwart.

Notwithstanding the growing influence of the hareidim, Arazi promised the Hurva will be operated for the general public, including Jewish Quarter residents, Israeli visitors and foreign tourists. But with only 200 seats in the vast building, it remains to be seen who the congregants will be.

During the opening week, the JQDS will conduct tours during the day and will show a son et lumiere presentation during evening hours – for free.

• • •

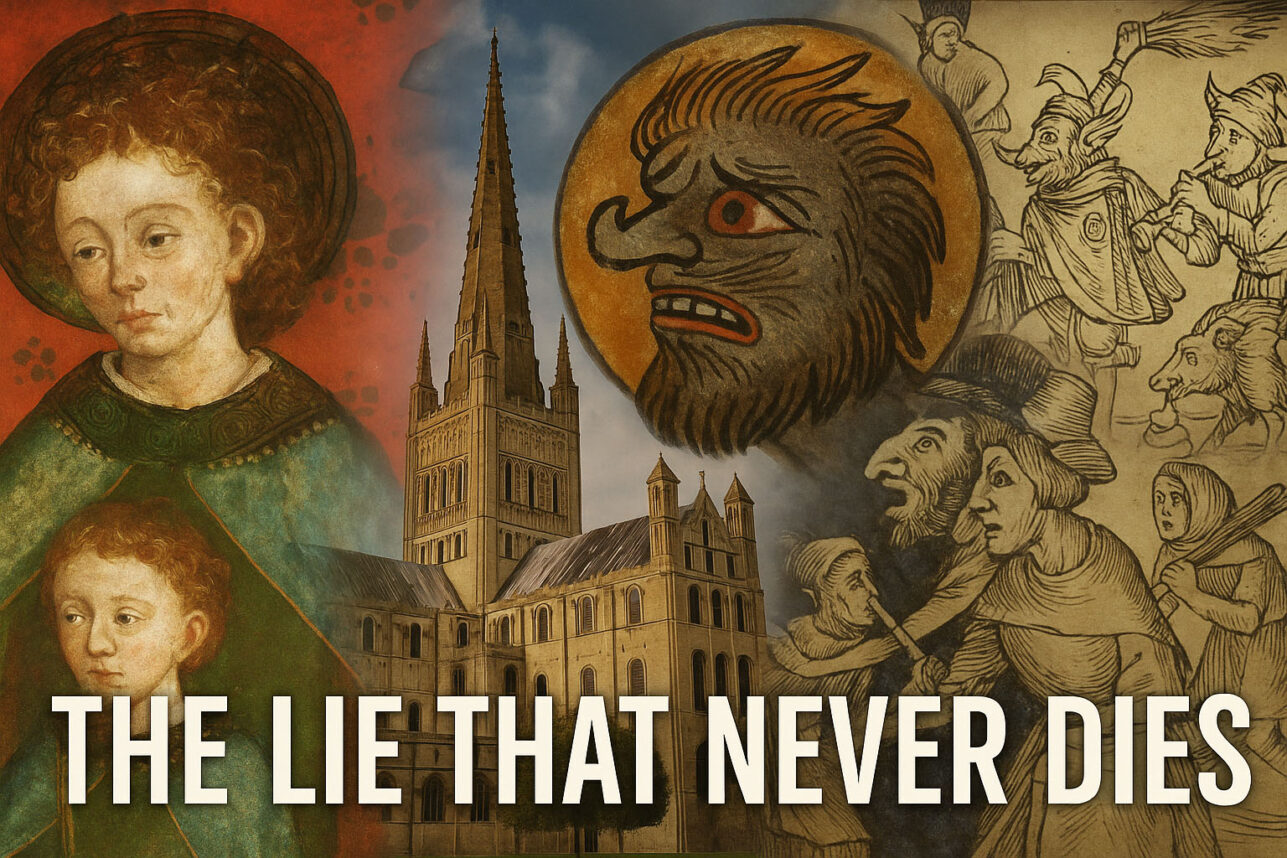

The Hurva, literally “The Ruin” symbolizes the fortunes of Jerusalem’s yishuv over the last three centuries. In 1700, Rabbi Yehuda he-Hassid (Segal), a preacher who may have secretly believed in the false messiah Shabtai Zvi, led an en masse aliya of between 300 and 1,000 of his followers (sources vary on the number) from Siedlce, Poland to the Holy City. It was the largest immigration of Jews to the Land of Israel in centuries.

The group bought the courtyard next to the Ramban Synagogue – which itself stood on the ruins of the Crusader church of St. Martin. The Ramban synagogue, named for the Spanish sage Moshe ben Nachman who founded the house of worship in 1267, had been closed by the Ottomans in 1589 due to Muslim incitement. Here the rabbi and his Ashkenazi followers began building a large synagogue to accommodate the increased Jewish population of the city.

The project foundered on internal dissent, debt and the sudden death of the charismatic rabbi. In 1720 Arab creditors burned the unfinished structure together with the 40 Torah scrolls it contained. Whence the ruined site became known as Hurvat Rav Yehudah ha-Hasid — the Ruin of Rabbi Judah the Pious, or simply “the Hurva”.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.