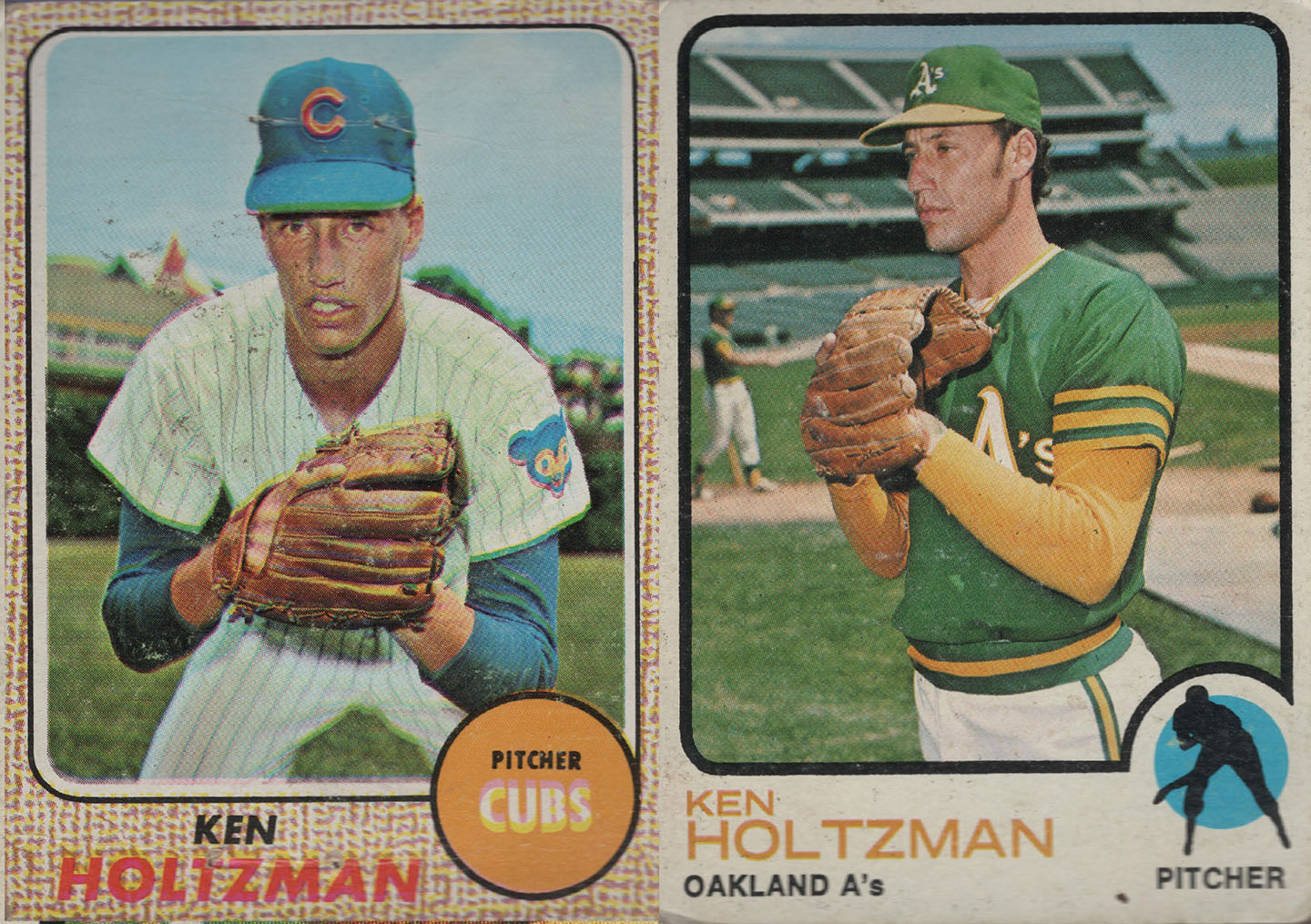

Photos by Richard Bartlaga/Flickr Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic

Photos by Richard Bartlaga/Flickr Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic Who was the winningest Jewish pitcher of all time? If you guessed Sandy Koufax, you’re wrong. It was Ken Holtzman, who died on Sunday, April 14 at age 78.

As a hard throwing Jewish left-handed pitcher, Holtzman was heralded as “the next Sandy Koufax,” who was his boyhood idol. There was no way that Holtzman could live up to Koufax’s iconic status.

Even so, Holtzman was an outstanding pitcher. During his 15-year career, Holtzman, a southpaw like Koufax, had a 174-150 won-lost record. (Koufax was 165-87). Holtzman threw no-hitters for the Cubs in 1969 and 1971. He was an All-Star in 1972 and 1973. He was a top pitcher for the Oakland A’s dynasty that won three consecutive World Series championships between 1972 and 1974. In 1973 he started 40 games for the A’s and had a 21-13 won-lost record. He pitched in eight games in five World Series and was 4-1 with a 2.55 ERA. He won at least 17 games in six different seasons. Among Jewish pitchers, Holtzman’s 1,601 career strikeouts and 30 career shutouts are both second to Koufax’s 2,396 and 41.

Holtzman was born in St. Louis on November 30, 1945. His father, Henry Holtzman, was in the machinery business. His mother, Jacqueline, was a homemaker. Although his family attended a Conservative synagogue, Holtzman celebrated his bar mitzvah at his grandparents’ Orthodox synagogue.

He pitched for University City High School, winning 31 games and losing only three. After graduating in 1963, he enrolled at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana, where he pitched for the baseball team. The Chicago Cubs selected him in the fourth round of the 1965 amateur draft during his sophomore year. He quit college to join the Cubs later that year.

Holtzman spent less than one season in the minor leagues. He had an inauspicious debut with the Cubs. Brought in as a reliever against the Giants in the ninth inning on September 4, 1965, he gave up a home run to Jim Ray Hart on his first major league pitch, but then got the next three batters to fly out.

In his second year with the Cubs, he returned to college, taking morning classes at the University of Illinois’s Chicago campus so he could join the team for afternoon and night games in Chicago and away games during weekends. Holtzman graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration and French.

In 1967 his Cubs career was interrupted by his service in the National Guard, when he was also only available to play on weekends. He nevertheless compiled a 9-0 won-loss record and a 2.53 earned run average that season

Holtzman’s and Koufax’s careers briefly overlapped. During his rookie year, when the Cubs were playing in Los Angeles, Holtzman went in to the Dodger’s clubhouse and got Koufax’s autograph to give to his mother, who worshipped the Dodger pitcher.

The next year, Holtzman and Koufax competed in one of the greatest pitching duels in major league history. On September 24, 1966, which happened to be Yom Kippur, the Cubs were playing the Dodgers at Chicago’s Wrigley field. Both Koufax and Holtzman (then a 20-year old in his second major league season) refused to play. The next day, Holtzman beat Koufax 2-1. Holtzman had a no-hitter going into the ninth inning, but gave up a single to the Dodgers’ Dick Shofield, then surrendered another hit and gave up a run. Koufax gave up four hits. “I was satisfied with my performance,” Koufax told the Los Angeles Times, “but Ken was too good for us today.”

Koufax pitched his last regular-season game a week later, on October 2, retiring at age 31 because of serious injuries.

Holtzman was an outspoken union activist during the early days of the MLB Players Association. He was a member of the union’s pension committee and the player representative for the A’s and the Yankees.

Holtzman once told a reporter that he had read Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past” in the original French. Sportswriters started calling him “The Thinker” after that.

Within a year after he joined the Cubs, Holtzman, the only Jew on the roster and one of the few players with a college degree, faced antisemitic bigotry from manager Leo Durocher. Durocher constantly berated Holtzman and called him a “kike” and “gutless Jew” in front of his teammates. According to one analysis, “Holtzman’s background—specifically his upbringing as an observant Jew who refused to pitch on Jewish holidays and who adhered to Jewish dietary laws—contributed to Durocher’s increasingly antagonistic behavior toward Holtzman.”

Within a year after he joined the Cubs, Holtzman, the only Jew on the roster and one of the few players with a college degree, faced antisemitic bigotry from manager Leo Durocher.

The poorly-educated Durocher also resented Holtzman’s college education, his cerebral manner (he would read books in airport terminals while waiting for a flight), his ability to beat Durocher at gin rummy, and his strong pro-union attitude. In 1970, Durocher removed Holtzman from a game he was winning 6-4 with two outs in the fifth inning. Had he stayed in and gotten one more out, Holtzman would have been the winning pitcher.

Durocher’s abuses went beyond his mistreatment of Holtzman. By 1971, Cubs players had had enough of Durocher’s abrasive style and began to openly criticize him. Durocher called a clubhouse meeting where he ranted about the players and then stormed out, threatening “I quit.” The Cubs’ general manager tried to calm the players down, urging them to persuade Durocher to stay. “Let him go,” said Holtzman. The Cubs rehired Durocher for the 1972 season, but by the middle of the season they fired him.

By then, however, Holtzman was gone. In 1971 he demanded to be traded. After the season ended, the Cubs traded him to the Oakland A’s for outfielder Rick Monday. Holtzman joined the starting rotation that included Vida Blue, Catfish Hunter and Blue Moon Odom along with reliever Rollie Fingers, giving the A’s the strongest pitching staff in the majors and helped them win three consecutive World Series in 1972, 1973, and 1974.

On September 6, 1972, Holtzman and his Oakland teammate Mike Epstein wore black armbands on their uniforms during a game against the White Sox at Comiskey Park in recognition of the Israeli athletes who’d been kidnapped and murdered at the Munich Olympics by Palestinian terrorists.

During his 15-year career, he never played on the Jewish high holidays. He and his wife Michelle kept a kosher home, although he wasn’t able to keep kosher while on the road during the baseball season.

In 1973, the A’s were in Baltimore to play the Orioles in the American League championship series. Holtzman was scheduled to pitch the second game of the series, but he told manager Dick Williams that it was Rosh Hashana, so Williams changed the pitching rotation to accommodate his Jewish pitcher. Holtzman asked around about where to attend services in Baltimore. To his surprise, not only did Temple Israel send a limo to take him to the synagogue, but when he arrived, the rabbi greeted him on the steps outside the building.

“We’ve been waiting for you, we’re glad to have you,” the rabbi said, then walked Holtzman down to the front row, where he seated him next to Jerry Hoffberger, owner of the rival Orioles.

“After services he (Hoffberger) invites me over to his house, and he feeds me,” Holtzman recalled to Larry Ruttman, author of a book on Jews and baseball. “Everything was just terrific.”

The two teams flew to Oakland for the third game of the series. Holtzman beat the Orioles 2-1, pitching for 11 innings and giving up only three hits.

“That extra day of rest (on Rosh Hashana) left me feeling strong and refreshed,” Holtzman remembered.

After leaving the A’s, he pitched briefly for the Baltimore Orioles, New York Yankees, and a second tour with the Cubs. When his playing career ended in 1979, Holtzman worked as an insurance salesman and stockbroker. In 1996, he earned a master’s degree in education from DePaul University in Chicago and taught briefly in the Chicago public schools. He moved back to St. Louis to be closer to his parents and worked as the athletic director at the St. Louis Jewish Community Center.

For several years, he coached St. Louis’ baseball team for the Maccabiah Games. In 2007, he briefly managed the Pietach Tikva Pioneers in the Israel Baseball League’s only season, but he quit in the middle of the season, unhappy with the way the league was run, including the poorly maintained fields.

His marriage to Michelle Collins ended in divorce after 26 years. He is survived by his brother, Bob (a former minor league pitcher), three daughters and four grandchildren.

Peter Dreier is professor of politics at Occidental College. His most recent books are “Baseball Rebels: The Players, People, and Social Movements That Shook Up the Game and Changed America” and “Major League Rebels: Baseball Battles Over Workers’ Rights and American Empire.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.