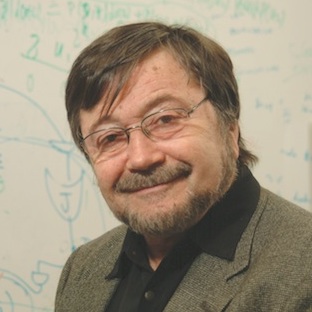

Daniel Kahneman attends a protest to advocate for Israeli democracy on September 22, 2023 in New York City. (Photo by Rob Kim/Getty Images for New York Protest Movement)

Daniel Kahneman attends a protest to advocate for Israeli democracy on September 22, 2023 in New York City. (Photo by Rob Kim/Getty Images for New York Protest Movement) Daniel Kahneman (1934-2024), who died last week at the age of 90, was born in Tel Aviv to Jewish Lithuanian parents who had emigrated to France in the early 1920s. He spent his childhood years in Paris under Nazi occupation and, after losing his father, returned to Tel Aviv in 1946, just before the creation of the state of Israel.

After studying psychology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and serving in the IDF in a combat recruiting unit, in 1958 he went to the United States to study for his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1969, he began to collaborate with another Israeli, Amos Tversky, and the two produced their seminal works on human thinking that led to the Nobel Prize in 2002. (Tversky died in 1996.) They discovered that humans are far from acting rationally when faced with uncertainty; they are in fact prone to systematic errors and biases, which can be described mathematically and, sometimes, corrected.

The captivating story of these two friends-researchers is narrated in the book “The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds,” by Michael Lewis (Penguin Random House, 2017).

I first met Daniel at a scientific conference in Michigan in the late 1970s, and I have remained a devout disciple of his theory throughout my work in artificial intelligence. In 2003, while editing the book “I Am Jewish: Personal Reflections Inspired by the Last Words of Daniel Pearl,” I asked him if he would share his thoughts on what “being Jewish” means to him. He sent me the following essay:

“I trace my vocation as a psychologist to my experience as a Jewish child in France, before and during World War II. Like many other Jews, I suppose, I grew up in a world that consisted exclusively of people and words, and most of the words were about people. Nature barely existed, and I never learned to identify flowers or to appreciate animals. But gossip was fascinating. The people my mother liked to talk about with her friends and with my father were fascinating in their complexity.

“Some people were better than others, but the best were far from perfect and no one was simply bad. Most of her stories were touched by irony, and they all had two sides or more.

“In one experience I remember vividly, there was a rich range of shades. It must have been late 1941 or early 1942. Jews were required to wear the Star of David and to obey a 6 p.m. curfew. I had gone to play with a Christian friend and had stayed too late. I turned my brown sweater inside out to walk the few blocks home. As I was walking down an empty street, I saw a German soldier approaching. He was wearing the black uniform that I had been told to fear more than others the one worn by specially recruited SS soldiers. “As I came closer to him, trying to walk fast, I noticed that he was looking at me intently. Then he beckoned me over, picked me up, and hugged me. I was terrified that he would notice the star inside my sweater. He was speaking to me with great emotion, in German. When he put me down, he opened his wallet, showed me a picture of a boy, and gave me some money. I went home more certain than ever that my mother was right: people were endlessly complicated and interesting. It seemed that even the SS soldier had more than one side to him. I also remember struggling as a child with the troubling thought that the monstrous Hitler enjoyed flowers and was tender to babies. If there was some good even in Hitler, then evil could not be simply described as the thing that evil people do, evil people were a puzzle to be understood. Understanding did not imply forgiving: it was all right to hate, and a duty to resist. But the complexity of evil and the fallibility of the good have been with me all my life — perhaps the first thing I think about when I think of being a Jew.”

“The complexity of evil and the fallibility of the good have been with me all my life — perhaps the first thing I think about when I think of being a Jew.” — Daniel Kahneman

My next Jewish-related interaction with Daniel came in 2010, when the BDS movement began to raise its ugly head in academia, and I was recruiting scientists of stature to express opposition to the idea of boycotting Israel. Daniel immediately added his name to the list of 32 Nobel Laureates who denounced calls for boycotts and sanctions against Israeli academics.

The last email that I received from Daniel contained a personal surprise. Having read my book, where I mention some of my high school teachers, he wrote to me: “Hi Judea. Did you study in Tichon Irony Dati in Tel Aviv? I studied there in 1949, and had a wonderful physics teacher name Feuchtwanger. It seems to be too much of a coincidence…”

As it turns out we went to the same high school in Tel Aviv, two years apart in 1949-50, and had the same science teacher who introduced us to logic through a paradox in causal reasoning (see http://bayes.cs.ucla.edu/BOOK-2K/why.html). It must have been the magic of this science teacher that pulled each one of us, independently, into the fold of science.

I’ll end this tribute with a Mishnaic saying: “Aseh lecha rav, knei l’cha chaver.” — “Make for yourself a teacher, acquire for yourself a friend.” (Pirkei Avot 1:6)

Daniel Kahneman was a friend and a teacher. Am Israel and the entire scientific world will miss him dearly.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.