First he lived biblically, now he’s living like it’s 1787.

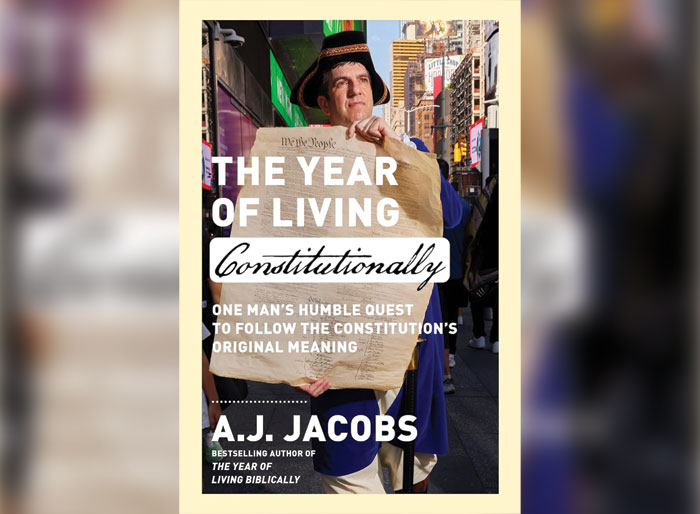

AJ Jacobs, the prolific stunt-author of “The Year of Living Biblically,” in which he decided to read the Hebrew Bible and keep God’s commandments, chapter and verse; “Thanks a Thousand,” which documents his gratitude for the hundreds whose work went into producing his morning cup of joe; and “The Puzzler,” recounting his attempts to solve the world’s toughest mazes, crosswords and riddles, is back — proudly sporting a tricorne hat and armed with a musket.

In “The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution’s Original Meaning,” Jacobs sets out, in characteristically wise and witty style, to understand America’s founding charter and see what lessons we might learn from it amidst today’s virulently polarized pre-presidential election times.

Tipping his cap, and the new book’s subtitle — which echoes that of its biblical predecessor, “One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible” — Jacobs, a Reform Jew who lives in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, notes how struck he was by the parallel projects. “I followed the Ten Commandments, but I also followed the hundreds of more obscure rules,” he reminds his readers. “I grew some alarmingly sprawling facial hair (Leviticus says you should not shave the corners of your beard) and tossed out my poly-cotton sweaters (Leviticus says you cannot wear clothes made of two kinds of fabric) … The project was absurd at times but also enlightening and inspiring.” Ultimately, in wrestling with a fundamentalist interpretation of a millennia-old document, he concluded:

“I found that some aspects of living biblically changed my life for the better (the emphasis on gratitude, for instance). I also learned the dangers of taking the Bible too literally (I don’t recommend stoning an adulterer in Central Park, even if those stones are pebble-sized, as mine were). And I learned how challenging it is to figure out what we should replace literalism with.”

Now Jacobs covers the Constitution, not quite yet two-and-a-half centuries young.

Scholars, he notes, have long described the Constitution as the sacred text of America’s civic religion. Jefferson called the delegates of the Constitutional Convention “demigods.” And, as in biblical interpretation, there is an endless debate between those who proclaim a fealty to the text’s ancient messages and others who argue its meaning evolves with the times.

Jacobs, adorned in garb that would make George Washington proud, balances a close reading of sections of the Constitution with his humorous, light touch.

Jacobs, adorned in garb that would make George Washington proud, balances a close reading of sections of the Constitution with his humorous, light touch. Take, for example, his comments on the opening 52 words:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Here’s Jacobs’ reaction:

“I love how it builds tension, comma by comma by comma, till we get to the majestic and self-referential phrase ‘this Constitution.’ I also like the mention of the ‘general Welfare.’ We could all use more attention to the “general Welfare” nowadays as a balance to America’s focus on individual rights. I’m also a fan of the mention of ‘Posterity’ — that’s us they’re talking about. We’re the posterity. I’m a part of this American experiment.”

Following a quip about the “promiscuous” use of capital letters by the Founders, Jacobs admits that the subsequent rules for setting up Congress are “technical and lawyerly … like the instructions to a complicated board game — like ‘Settlers of Catan,’ but the players are the branches of government.” While the typical citizen probably doesn’t have strong feelings on the instructions that “the Votes of both Houses shall be determined by yeas and Nays” and “No Person shall be a Senator who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty Years, and been nine Years a Citizen of the United States,” the Constitution does remain a national Rorschach test, with everyone, including, admittedly, Jacobs himself, seeing what values they want in it.

“Does the Constitution support laissez-faire gun rights, or does it support strict gun regulation? Does it prohibit school prayer or not? Depends on whom you ask. And it’s not just the issues we’re divided on — it’s the Constitution itself. Is the Constitution a document of liberation, as I was taught in high school? Or is it, as some critics argue, a document of oppression? Should we venerate this brilliant road map that has arguably guided American prosperity and expanded freedom for 230-plus years? Or should we be skeptical of this set of rules written by wealthy racists who thought tobacco-smoke enemas were cutting-edge medicine?”

On his quest to gain a better understanding of the Constitution’s intent and impact, Jacobs commits to “walk the walk and talk the talk and eat the mutton and read the Cicero,” just as they did in Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson’s day. He drafts the book with a goose quill, votes in a local election by voice, and hands out then-traditional eighteenth-century “election cakes” near a voting booth — an offer met by one curious onlooker with that most modern of queries, “Is it gluten-free?”

With his bemused family begrudgingly shlepping along for the endeavor, Jacobs participates in a reenactment of the 1776 Battle of Ft. Lee. He traces the history of women’s rights and the quest to abolish slavery. Free speech and federalism are analyzed and argued over. He even voluntarily quarters (i.e. houses) a soldier in his home. Hilariously, Jacobs and his son attempt to pay for a dinner with gold and silver due to the Founders’ distaste for paper money. The meal is for liberals and conservatives to debate originalism vs. living constitutionalism, naturally.

Jacobs hardly leaves a constitutionally-relevant topic unexamined. All the while he consults with legal experts and laypeople alike for their insights and perspectives, framing the debates that still rankle our republic.

Jacobs ultimately emerges having gained an appreciation for the Constitution’s, and its authors’, emphasis on the common good, deliberate thinking and having an experimental mindset, and the early Americans’ dislike for aristocracy. And he expresses profound awe at the gift that is being able to cast a vote in an election.

“The Year of Living Constitutionally” concludes by alluding to the story of Benjamin Franklin’s reaction to noticing the image of the sun, cut in half by the horizon, that adorned the wooden chair that Washington sat on as the Constitution was drafted. Franklin opined, at the end of the convention, that the sun, and America, was rising. Jacobs offers his own take:

“My year of immersing myself in the founding of this country has inspired me to fight as hard as I can to protect it … I’m not certain of much, but I’m sure of one thing: Whether the sun sets or rises on democracy, that’s up to us, we the people.”

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.