In “Anna Karenina,” Tolstoy writes that Konstantin Levin, “like most of his contemporaries, was in a very uncertain position” when it came to religion. “He could not believe, yet at the same time he was not firmly convinced that it was all incorrect.”

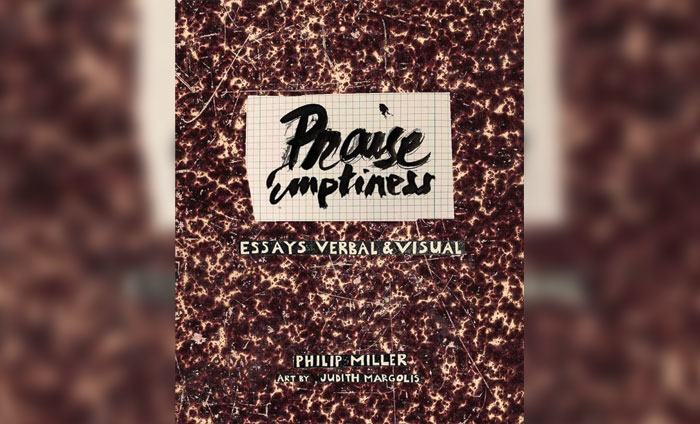

Philip Miller, author of the new collection of “verbal & visual” essays, “Praise Emptiness” (Bright Idea Books, 2023), finds himself in the same position—though not solely in relation to religion.

Judaism, Buddhism, Existentialism, Nihilism, Leibowitzian postmodernism — all of these isms have a hold on Miller’s consciousness, even as he rejects them or ultimately finds them unsatisfying.

Is the self real? Is God real? Or are these just words that we use to “praise emptiness” and give shape to chaos? Miller is unsure.

If there is a cure for this chronic philosophical uncertainty, it is the idea of objective pluralism — a concept taken from an Isaiah Berlin essay on Machiavelli. According to Miller, objective pluralism is the idea that contradicting realities can both be true.

This is not relativism. In fact, it is a rejection of relativism. The idea that a flower, when seen under a microscope, is revealed to be a vast network of cells, does not negate or relativize its reality as a flower, as a singular being and a delight to the eye.

Miller returns to this idea again and again throughout the book as a way of making peace with the contradictions that characterize his inner life. Armed with this concept, God can be real and not real; the self can be illusory and not illusory; and human will can be free and fated—all at the same time.

This idiosyncratic collection is mystical, searching and associative — not unlike the conversations one has with a close friend late at night or on a long car ride. Like such conversations, it ranges from the profound to the sophomoric. It is undoubtedly the work of a true philosopher — someone for whom the problems of philosophy are real and urgent — the kind of thing one loses sleep over.

Miller is not in the business of making arguments so much as he is in the business of having an argument — with himself, with God, and with the great thinkers of philosophical and religious history.

Miller is not in the business of making arguments so much as he is in the business of having an argument — with himself, with God, and with the great thinkers of philosophical and religious history. The range of interlocutors cited in this book reveal Miller’s breadth of curiosity and erudition. He is an avid reader of philosophy, history and science and well versed in the luminaries of Jewish thought from Rav Kook to the Ramchal.

The essays are accompanied by artwork from Judith Margolis — a Jerusalem-based visual artist and publisher.

Having had the pleasure of spending some time with Judith, I can say that she is also someone who — like Tolstoy’s Levin — can neither fully believe nor dispense with religion. And like Philip Miller, her work reveals an inner world that is bright, busy and crowded with images, ideas, and influences.

The included artworks are not illustrations for Miller’s essays. They are essays in and of themselves — riotous and captivating paintings, collages, and photos which work through the thorniest questions of what it means to be a human being, a Jew, and a woman.

The included artworks are not illustrations for Miller’s essays. They are essays in and of themselves—riotous and captivating paintings, collages, and photos which work through the thorniest questions of what it means to be a human being, a Jew, and a woman.

The words and images work beautifully together on a conceptual level. On a material level, however, there are some difficulties. Praise Emptiness is a coffee-table book with large, glossy pages. This is great for an art book, but less ideal for essays. Reading essays is an intimate thing for which a smaller, more portable format is better suited. The glossy pages also have the effect of discouraging dog-earring pages or taking notes.

The book begins with a striking epigraph from Franz Kafka taken from a letter to his sister. He writes of seeing a girl in Berlin smile at him and say something. “Naturally I smiled back at her in an overly friendly manner … until I began to realize what she had actually said to me: ‘Jew.’”

The final essay in the collection is titled “It’s Hard to Be a Jew,” in which Miller discusses the “bleak predicament” of the nonbeliever.

These two bookends seem to be the rock and the hard place of Miller’s Jewish soul. On the one hand, in a world hostile to Jews, Jewish identity is not something we have the ability to take or leave. On the other hand, in our postmodern age, Jewish religion may not be something that we can embrace with simple, untroubled faith.

Perhaps that’s ok. As Yuval Noah Harari (one of the many authors cited in the book) is fond of pointing out, “tensions, conflicts and irresolvable dilemmas are the spice of every culture.”

They are certainly the spice of Jewish culture, as well as of this lively collection, which would be enjoyed by every Jew who finds that he or she cannot quite believe, nor be firmly convinced that it is all incorrect.

Philip Miller will be reading from Praise Emptiness Wednesday evening, May 15 at 7:30 PM at Village Well Books & Coffee, 9900 Culver Blvd. Culver City 90232

Matthew Schultz is a Jewish Journal columnist and rabbinical student at Hebrew College. He is the author of the essay collection “What Came Before” (Tupelo, 2020) and lives in Boston and Jerusalem.