Yocheved, the mother of Moses, merits nary a mention after her son grows up. When Israel’s future liberator was born, she daringly defied Pharoah by hiding the boy in a basket of reeds set upon the Nile. After the baby’s discovery by Pharaoh’s daughter, Yocheved nursed the child in his early years, having been hired by the princess to be the caretaker for her own biological offspring.

While the Bible records few details about her life outside of this episode, the ancient rabbis fill in the blanks.

The Talmud records that Yocheved was conceived along Jacob’s family’s way from Canaan to Egypt, and born between the country’s entry walls. Through her righteousness, she merited living through the length of the enslavement in Egypt, and left as the people were led by her son.

The Talmud records that Yocheved was conceived along Jacob’s family’s way from Canaan to Egypt, and born between the country’s entry walls. Through her righteousness, she merited living through the length of the enslavement in Egypt, and left as the people were led by her son.

Why was she named Yocheved? Because her face had a semblance of the Divine radiance, ziv hakavod, suggested the Midrash HaGadol.

Professionally, she was a midwife. That civilly disobedient pair who were ordered by the Egyptian monarch to kill Jewish babies upon their birth but did not listen to the murderous command? Though named Shiphrah and Puah in the text, they were actually Yocheved and her daughter Miriam, Moses’ sister.

Why was her alternate name Shiphrah? Because she would cleanse, meshaperet, the newborns, by washing and cleaning them after birth. Or because by merit of her deeds, the Israelites were fruitful, she-paru, multiplying due to her kindness.

She also had yet another name, Yehudiyah. Why? Because through this courageous disobedience, per Vayikra Rabbah, she allowed many Yehudim — Jews — to be brought into the world.

Young Miriam, the Talmud notes, had talked her mother into reconciling with Yocheved’s husband, Amram. After all, the couple had initially separated after Pharaoh’s decree, lest they make any more children who would be marked for murder. Her being blessed with another child was a divine reward for her having saved so many. The “fear of the Lord” that had led her to spare the Jewish children was repaid with mothering God’s great lawgiver.

Yocheved was no spring chicken when she delivered Moses — she was 130 years old. Her husband was much younger — after all, she was his aunt. And Moses’ name wasn’t originally Moses. Yocheved named him Tov, “good,” per Exodus 2:2’s noting that upon seeing him she realized “how good [tov] he was.”

When she placed him in that reed basket, she was sure to adorn it with a little canopy, for “she said to herself: Perhaps I will not see him under his wedding canopy” after he survives and grows up, says the Talmudic tractate Sotah.

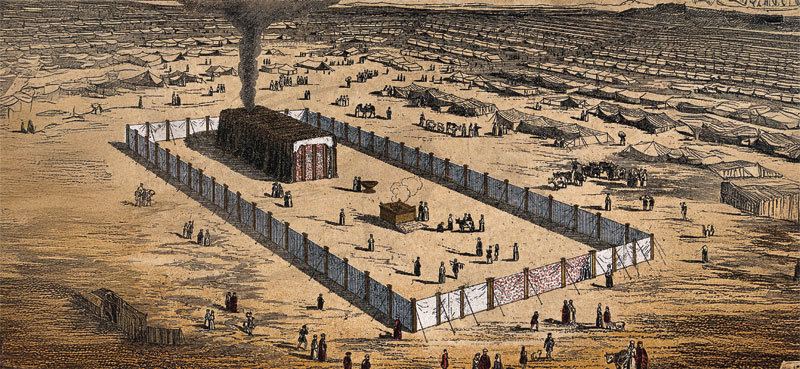

All three of Yocheved’s children merited miraculous gifts that accompanied the Israelites during their desert wanderings. Moses gifted the people the manna for sustenance. In recognition of Miriam’s greatness, a water-filled well accompanied them wherever they went. And brother Aaron, the High Priest, was the one in whose honor God had the clouds of glory surrounding the Israelites and protected them during their journeying.

Even since she passed away, Yocheved occupies a special place in heaven. The Zohar describes how she leads a special chamber there with thousands of women, where “three times each day, she acknowledges and praises the Ruler of the world, she and all the women with her.” They sing the Song of the Sea, the victory hymn proclaimed after Pharaoh’s forces drowned in the Red Sea, every day, and cite the verse about her daughter, “And Miriam the Prophet … took her timbrel in her hand …” (Exodus 15:20). And, the mystical text adds, “so many holy angels acknowledge and praise the holy Name with her.”

In the meantime, before she was laid to rest, Yocheved completed the journey begun with the Exodus. The one whose name evokes the word kavod, threaded throughout the Bible’s second book — from the heaviness of Pharaoh’s heart (kevad lev) to God’s glory (kevod Hashem) descending on the Tabernacle built by the liberated Israelites — makes it to the end of the entire Five Books of Moses. Seder Olam Rabbah records that Yocheved entered the Promised Land. The mother of Moses, born on the cusp of slavery, merited living out her days in the place designated by God for the people whom her son had liberated.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.