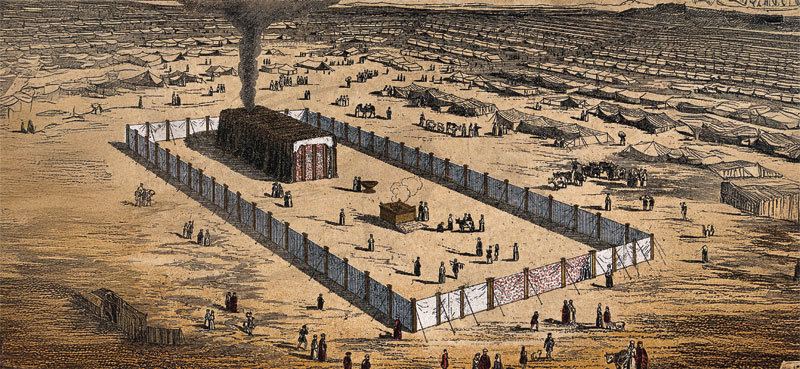

As a child of Iraqi Jews, The Farhud has forever been a part of my memory and the holiday of Shavuot will always be shadowed by this tragic event. My grandfather always attributed the death of his father, a successful doctor in Baghdad, to the shock and heartbreak of seeing the violence unleashed on his community. The Jewish community, which dated back to the exile of Nebuchadnezzar, had thrived for centuries, coexisting with their Muslim and Christian neighbors. By 1941, elite Baghdadi Jews were high-ranking officials, dignitaries, attorneys and wealthy merchants, who owned a majority of the businesses in Baghdad.

The Farhud, which means “violent dispossession” was a pogrom that erupted against the Jews of Baghdad on Shavuot, June 1, 1941. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the British had a Mandate in Iraq. They appointed a King, Faisal I and gave many civil rights to the Jews. In April, 1941, the pro-British government was overthrown by the ultra-nationalist Rashid Ali, with the support of four high-ranking Iraqi Army officers, known as the “Golden Square” and Haj Amin Al-Husseini, the exiled Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. For years, the Iraqi populace had been primed for violence through the efforts of the Grand Mufti Haj Amin and the Nazi German ambassador. Arabic-language radio broadcasts aired antisemitic propaganda from Berlin. Yunis al-Sabawi had translated “Mein Kampf” into Arabic and it was serialized in the “Arab World” newspaper Al Alam al Arabi. The latter had also groomed Muslim youth in the Futtuwa, modeled on the Hitler Youth movement.

When the British Army decided to reoccupy Iraq, the coup leaders escaped to Iran. The Jews of Baghdad thought that the dangers had passed and went out to celebrate the festival of Shavuot.

There are no coincidences in life. Last week, my uncle Moshe, my father’s eldest brother, passed away at the age of 95.

As I sat down to write this story, my brother, Rabbi Natan Halevy, sent a recording of Moshe’s account of surviving the Farhud. He described the house that his father had built for the family in Karrada, away from the tightly built ancient Jewish neighborhood in the center of Baghdad. At first, the Futtuwa youth were hurling rocks at their house, which was scary but didn’t inflict much damage because a metal fence and strong gate surrounded the property and metal grilles protected the windows. He and my uncle Shlomo stood on the roof for hours, throwing rocks back at the youth. But then, soldiers and policemen began firing live ammunition in the neighborhood and they realized they could no longer defend themselves. My grandfather asked their Egyptian Moslem neighbor for help. The neighbor allowed the family, including my great-grandmother Farha, my 5-year-old father and his young siblings, to shelter in their backyard.

Many Jews were not as lucky. Mobs of rioting civilians joined the soldiers, policemen and youth in two days of mayhem. While the British Army waited on the edge of Baghdad, it is estimated that 200 Jews were slaughtered, 1,000 were maimed and injured, many young women were gang-raped, 600 homes were destroyed and many, many businesses were looted.

Decades later, my father would laugh at the memory of their neighbor’s wife, who exacted payment from my grandmother for the last decade that his family lived in Baghdad. At least once a week, she would come to their home with a cup or a bowl asking my grandmother Rosa for a cup of sugar or some other household commodity, which she had “run out of.”

—Sharon

This year, Sharon and I were honored to be part of the Kahal Joseph Congregation commemoration of the Farhud. There was a conversation moderated by Sharon’s brother Rabbi Natan Halevy, which was an incredible opportunity to hear from our good friend Joseph Samuels, who survived the Farhud as a young boy. He is the author of the book “Beyond the Rivers of Babylon,“ subtitled “My Journey of Optimism and Resilience in a Turbulent Century.”

Joe is the most incredibly uplifting and inspiring man, who single-handedly rebuilt his life after escaping Iraq with the clothes on his back. As Joe told us his story, one line resonated with me. He said “I was a refugee for one year. That’s it. Then I went to work and I studied.”

We also heard from Joe Dabby, author of the book “No Looking Back,“ who described life in Iraq after the mass Aliyah of the Jewish community in Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, in the early 1950s. He told stories of the curtailing of Jewish civil rights, including a ban on Jewish homes having a telephone. He told of the execution of Jews and his own arrest and fearful, furtive escape from Iraq with his wife, Yvette, our dear friend.

—Rachel

I always joke that I am the child of refugees. It’s meant to be funny, but I know that there is some truth to it. There is the memory of trauma, an entire community literally marked for violence and destruction with red palm prints marking Jewish homes just before the Farhud.

Fortunately, my family, and countless other Iraqi Jews, brought with them their rich heritage, their tefilah (prayer), their songs, their traditions and of course, their amazing recipes.

Fortunately, my family, and countless other Iraqi Jews, brought with them their rich heritage, their tefilah (prayer), their songs, their traditions and of course, their amazing recipes. They rebuilt their lives in Israel and the Diaspora. One of those traditions is to make the best Iraqi breakfast. Also known as Sabich, the rolled up laffa sandwich is made with brown eggs, “bethi mel Shabbath” and golden fried eggplant, “baban’jan.” This week, we were inspired to share with you Rachel’s recipe for crispy, spicy chickpeas. We serve them with creamy hummus as part of this amazing spread that works for breakfast or at any time of the day.

—Sharon

Crispy Spicy Chickpeas

1 15.5 oz can of chickpeas, drained and rinsed

1 Tbsp extra virgin olive oil

1 tsp garlic powder

1/4 tsp salt

1 tsp paprika

1/2 tsp Aleppo or cayenne pepper (optional)

Black pepper to taste

Preheat oven to 450°F and place a rimmed baking sheet in the oven while it preheats (this ensures the chickpeas crisp as soon as they hit the hot pan).

Pat chickpeas dry with paper towel (any residual moisture will cause the chickpeas to steam instead of crisp).

Toss the chickpeas with olive oil, salt and spices.

Carefully remove the baking sheet from the oven, place the chickpeas in an even layer.

Roast chickpeas for 10 minutes, then shake the pan.

Continue baking until chickpeas are golden and crispy, about 10 to 15 minutes.

Allow to cool and serve over hummus or salad.

Sharon Gomperts and Rachel Emquies Sheff have been friends since high school. The Sephardic Spice Girls project has grown from their collaboration on events for the Sephardic Educational Center in Jerusalem. Follow them

on Instagram @sephardicspicegirls and on Facebook at Sephardic Spice SEC Food. Website sephardicspicegirls.com/full-recipes.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.