When she was seventeen years old, novelist Evelyn Toynton and her sister were taken on a Grand Tour of Europe with their moody yet extravagant Uncle Hans. Their last night in Paris, they had dinner with a man who told them about his family’s terrible sufferings during World War II, after which Toynton said reproachfully to her uncle, “I don’t see how you can not hate the Germans.” She relates: “[My uncle] grabbed me without warning, shaking me so ferociously that the wind was knocked out of me, and screamed that they hadn’t known, nobody had told them what was really going on; the Nazis were only the scum, the German people had hated them, too, but what could they do, they had the guns; it was my precious English who had invented concentration camps…”

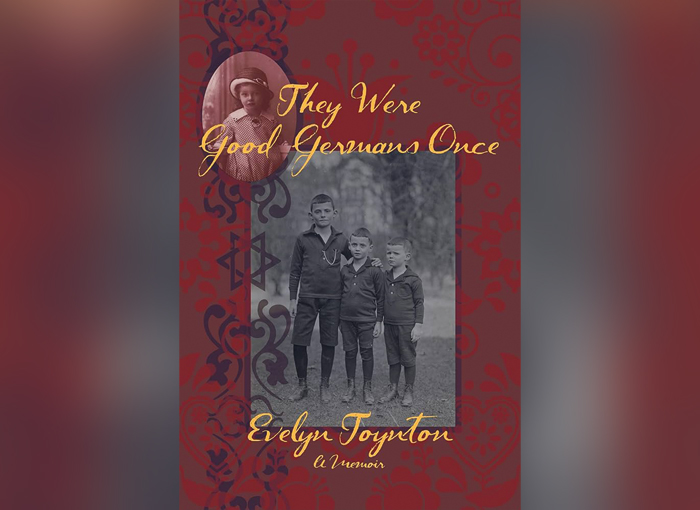

This scene comprises the backbone of Toynton’s fascinating memoir, “They Were Good Germans Once: My Jewish Émigré Family.” This slim volume (I devoured it in a day) is less an account of Toynton’s life than it is a collage of her family, with various members navigating complicated emotions about a homeland—Germany—that in their youth seemed to offer culture, prosperity and acceptance, only to savagely betray them because no matter how assimilated they were, no matter how deep their loyalty and love for their country, they were Jews.

Despite their good fortune in escaping Germany for new lives in America and elsewhere, each of Toynton’s relatives, with their German accents and German ways, their love of Schiller and Beethoven, is forced to reconcile his or her knowledge of what their country did to Jews, with lingering attachment they may have for the land and its people. No figure in Toynton’s memoir is so tormented as the above Uncle Hans, who she remembers in his beloved hometown, Nuremberg, his face revealing “bewilderment at the vagaries of history, at what had been done to him, which was so much less than what was done to so many others, and yet enough to leave him marooned for life.”

The memoir’s early chapters struck a personal note. The stories about growing up in America in a thoroughly assimilated, secular Jewish family so closely resembled aspects of my own maternal Dutch Jewish family I found it almost eerie. No one in Toynton’s family spoke, even in whispers, about the Holocaust; aged ten Toynton discovered “The Diary of Anne Frank” on her own and was powerfully affected by it, but understood it was a subject not to be discussed.

The silence was studied and selective. When Toynton was young, her grandmother had a friend, a fellow German refugee, who walked with a limp because an SA man threw her down a flight of stairs during Kristallnacht; whose husband was beaten to death in Dachau; whose two sons had been murdered in Auschwitz—but all her grandmother ever told Toynton about this friend was that she had prevented Toynton’s grandmother from perfecting her French, because she was forever luring her out to play tennis. (For all my grandmother’s sufferings at the hands of the Germans, the only charge I ever heard her make against them was that they’d stolen her horses.) When it came to those who populated Toynton’s early life, a tacit understanding prevailed that certain experiences were literally unspeakable.

Of all the relatives profiled in Toynton’s memoir, only her Uncle George, or Giora, Hans’ brother, apparently responded to the Nazi rise to power by embracing his Jewish identity and becoming a fervent Zionist. He refused to celebrate Christmas with the family and married a German Jew his horrified parents called a “shtetl Jew”—because her family actually practiced Judaism. He smuggled money, people and maybe arms into Palestine during the British Mandate; brought his parents to live there in 1939; and had a hard life in Palestine before becoming a significant enough political figure that today in Israel, according to Toynton, “there are hospitals and schools and streets bearing his name.”

Because he died before Toynton could really know him, most of the chapter about this uncle is related through his widow, Senta, that “shtetl Jew” who went with him to Palestine. Toynton describes Senta as a brusque, stoic, no-nonsense woman she didn’t know if she liked, but who made Toynton feel humble, “a smaller person than she was.” It was Senta who inspired Toynton’s WASP husband to remark, mournfully: “You think when you marry a Jew, you’re going to be part of this warm, loving family that hugs you and tells you great stories and gives you delicious things to eat. I got a bunch of Krauts.”

That Zionist uncle and his wife aside, the men and women of Toynton’s memoir visibly struggle with a desire to belong, retrospectively, to a country they consider, despite everything, as culturally superior. “They had all thought of themselves as Germans, after all, that being the only identity they’d been taught,” Toynton writes. “None of them had been given religious training, celebrated Jewish holidays, attended a synagogue except for weddings and funerals—and even weddings, in my uncle’s case, were often civil affairs, since many of the family married Gentiles. They had prided themselves on their assimilation; Germanness had pervaded their lives; and suddenly permission was withdrawn, they were not allowed to be German any longer.”

Upon moving to America, the schism between “shtetl Jew” and assimilated Jew was imported. Assimilation had failed in Germany, but in America, they seemingly believed, it was not only the path to acceptance, but the sign of enlightenment over religious backwardness.

Upon moving to America, the schism between “shtetl Jew” and assimilated Jew was imported. Assimilation had failed in Germany, but in America, they seemingly believed, it was not only the path to acceptance, but the sign of enlightenment over religious backwardness. When Toynton’s sister became a practicing Jew, her mother was appalled. (“If this were television, I would turn it off,” she whispered to Toynton during the bar mitzvah of one of her grandsons.) The “good Germans” of Toynton’s title became good Americans, as indistinguishable as possible from their neighbors.

But not all assimilations are created equal. As much as they preferred assimilation into crass Americanism to a regression back to Jewish shtetlism, there is still a poignant if grudging nostalgia for the high culture of their former German lives. With the vagaries of history come the vagaries of identity.

Still, it is impossible to read this book, in post-October 7 America, without reflecting on the apparent limits of assimilation in this very country of freedom. Jews are still welcome in American universities, liberal political and professional groups and institutions, but, in many cases, only if they renounce their Zionism. A familiar dilemma presents itself, in which Jews are forced to weigh their attachment to their people against their desire, and need, to belong in the country they love. Toynton’s memoir is a reminder that nothing is new under the sun.

Kathleen Hayes is the author of ”Antisemitism and the Left: A Memoir.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.