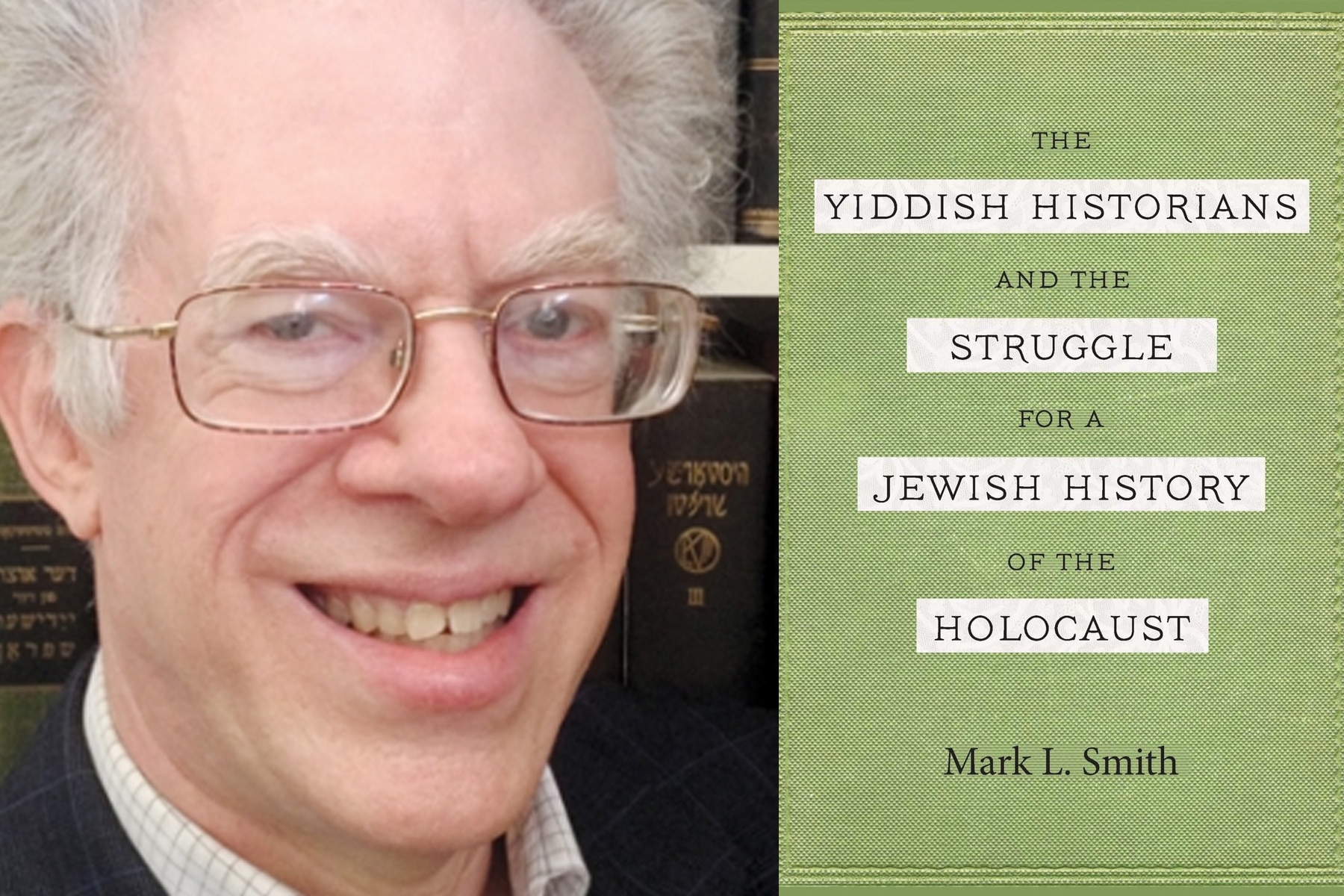

Mark L. Smith’s “The Yiddish Historians and Struggle for a Jewish History of the Holocaust” (Wayne State University Press) is a significant work. A successful architect turned historian, Smith explores the life and work of five Yiddish historians, all steeped in the prewar tradition of Yiddish historiography, who chose to continue their historical work in the language of those they left behind. Theirs was an act of homage to those who died in the Holocaust and of solidarity with their fellow survivors.

Educated in a trilingual culture, many spoke and wrote in many more than three languages. They came of age in interwar Poland but persisted doing their work in Yiddish even as they made their homes in Israel, Paris or New York.

They wrote for a broad readership explaining to them what happened to their own community. They wrote for a diminishing readership as the sons and daughters of the Yiddish reading public read in other languages.

Had postwar Poland been more hospitable to Jewish revival, they may have remained there, but after the pogroms, communism and Stalinism, they emigrated. The sparks of post-Shoah revival were quickly extinguished.

Who were these men? Philip Friedman (1901-60), Isaiah Trunk (1905-81), Nachman Blumenthal (1905-83), Joseph Kermish (1907-2005) and Mark Dworzecki (1908-75).

For whom did these men write?

They wrote for educated laypeople who wanted to understand their past. Many of their contemporary scholars prided themselves on the density of their scholarship, boasting of its inaccessibility.

What did they write about?

They wrote as participant observers of the everyday life of the Jews, not of their murders. Surprisingly, after all they had gone through, they were advocates of the anti-lachrymose theory of Jewish history, believing that Jewish history is not all about pogroms and persecution, anti-Semitism and discrimination but about the life of real people. Trunk said: “how the ghetto lived is no less important than the question of how it was murdered.”

They fiercely denied the uniqueness of the Holocaust; their critique was twofold. The uniqueness of the Holocaust is not connected to anything that the Jews did but is rooted in the Nazi accomplishment. Furthermore, they were categorically against the mystification of the Holocaust. Trunk was adamant: “If the Holocaust was regarded as unassailably unique therefore ineffable and unfathomable, it would elude the tools of historical inquiry,” and thus defeat the very nature of their historical efforts, singular and collective.

The Yiddish historians directly and unapologetically confronted the accusation that Jews went like sheep to the slaughter.

Many participated in the trial of Nazi war criminals by providing essential documentation, but they regarded that as a civic duty, seemingly unrelated to their historical task. When pressed, Nachman Blumenthal agreed to testify — “not as an accuser but as an expert.”

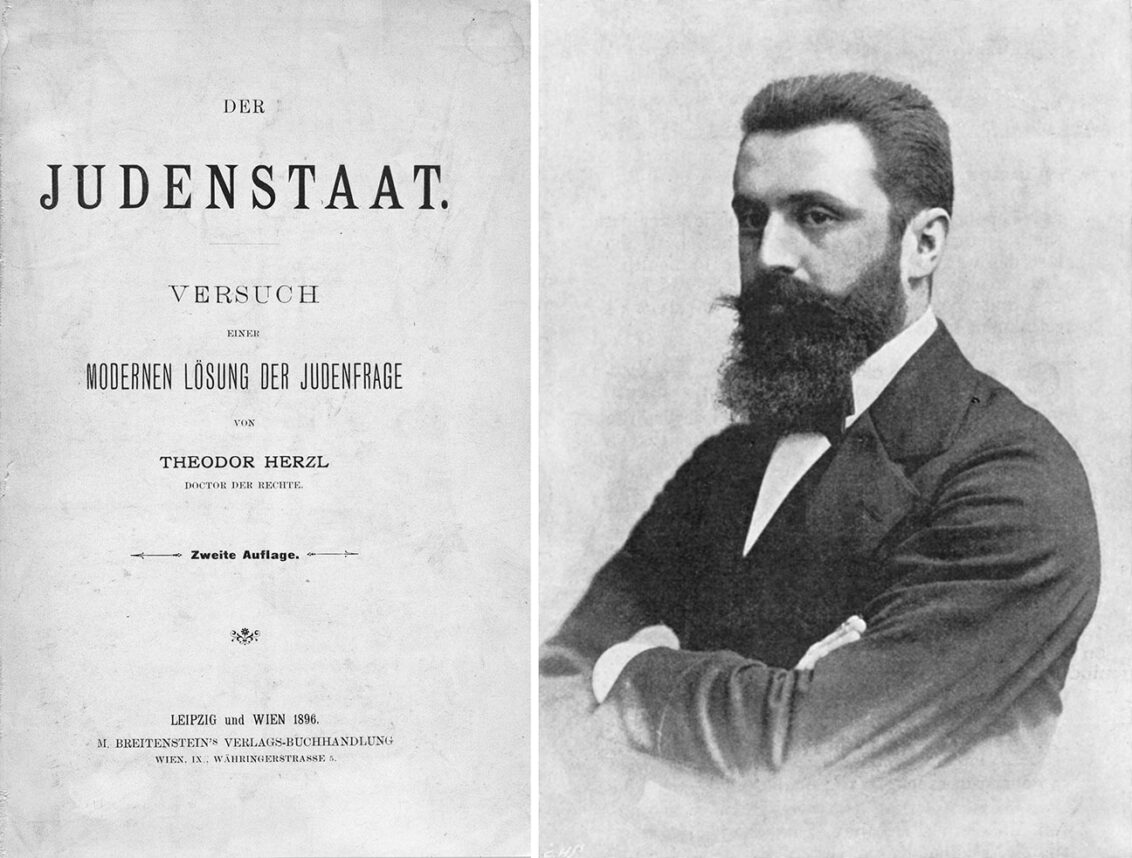

Those who went to Israel — Kermish, Dworzecki and Blumenthal — fought against the dominant Zionist ideology of shelilat hagolah [the negation of the exile]. They were unimpressed by efforts to create the “new Jew” and reticent to transfer their allegiance to the Hebrew language. The spearheaded an internal revolution within Yad Vashem where the primary emphasis in the years of its inception was on the role of the perpetrators. They argued that the task of the Jewish memorial was to tell the Jewish story. Their enduring legacy: Yad Vashem has depicted its new exhibition as telling the story from the Jewish perspective.

They were most willing to confront the dark side of Jewish behavior. Dworzecki’s admonishment: “Remain Silent or tell the whole truth.”

Smith depicts their collective achievement as redeeming Jewish honor by recognizing the many ways that Jews struggled to remain alive under Nazi domination.

These historians were pioneering. Long before feminists began to write about the role of women in the Holocaust, these Yiddish historians of the Holocaust — and they were all men — wrote of the unique role that women played both in the ghetto, when many men who could no longer provide for their family lost a sense of self-worth, and wives and mothers had to provide for the entire family. They depicted the role that women played in the resistance because their Jewishness could not be revealed by circumcision.

The Yiddish historians directly and unapologetically confronted the accusation that Jews went like sheep to the slaughter.

They detailed the obstacles Jews faced: The choice to resist was met by disproportionate punishment. The Nazis skillfully practiced the classical tools of domination: conquer and control, divide and rule.

Jews lacked arms or even sources for arms. Facing two enemies, the Nazis bent on their destruction and the native anti-Semites who were rewarded for turning in a Jew and punished often by death for shielding Jews, they could not count on the support of the local population.

Traditionally law abiding, Jews were often optimistic, a fatal communal and individual flaw when an enemy is determined to kill and destroy without restraint. Jews had illusions of faith in humanity and divinity, in the West and even in the German people.

These historians documented many instances of self-help. As a professor at Bar Ilan University, Dworzecki made his students work with survivors and listen to survivors at a time when they were still pejoratively called sabnonikim [soaps], referring to the discredited rumors that Nazis made soap from the fat of corpses of those who died in concentration camps.

Jews had to summon the inner resources to survive. Cultural activities were essential to combat depression and apathy. Religious observance and study preserved and enhanced the spirit. The very act of staying alive longer than the Germans predicted was an act of resistance.

Armed resistance was not the first instinct of Jewish leaders. They sought clarification and compromise, to plead, to bribe, to amend, to spiritually defy their masters, to seek religious solace and to work out some form of accommodation.

It was not a question of courage. Armed resistance was only one form of courage. It took courage for fathers to stay with their families, for mothers to comfort their children, for teachers to teach in the ghetto, for rabbis to remain with their congregants and for simple Jews to maintain their values.

Ironically, Yiddish historians avoided comparisons to the non-Jewish world. They did not ask — as others do — how was it that Soviet POWs, trained fighting men of military age unburdened by family and community, could die in massive numbers — 3.3 million — without rising in resistance.

Yiddish historians contend that spiritual resistance was the only means of resistance in which the great masses of Jews could and did engage in and which might reduce the threat of their immediate or eventual deaths. The concept of Amidah made its way into Holocaust history, standing up and remaining resilient in the face of oppression.

Smith’s research is voluminous. He devotes 90 pages to a bibliography of each of these five men, the books and articles by them and about them in the multiple languages in which they wrote. He has written a collective not an individual biography of men who knew one another, worked with and for one another, admired and liked one another, memorialized and celebrated one another — remarkable for a group of scholars.

They shared a common enterprise to write a history of the Jews, how they lived and how they endured what they had to endure, how they sought to preserve their honor and dignity in a world determined not merely to kill them but to dehumanize them. This book is not about the people who killed the Jews but about the Jews they killed.

Michael Berenbaum is director of the Sigi Ziering Institute and a professor of Jewish Studies at American Jewish University.