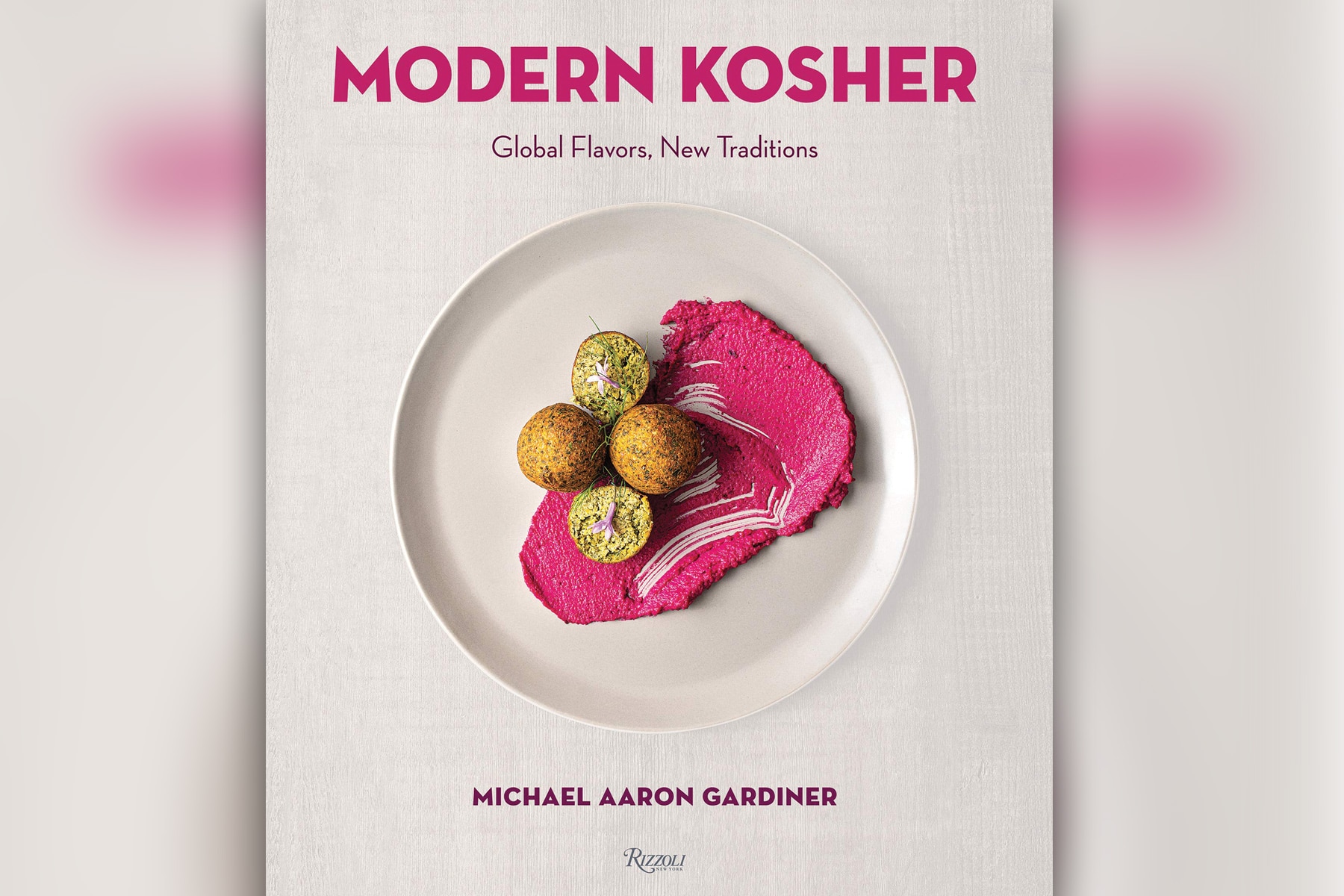

Now that we are all doing a lot more cooking at home, “Modern Kosher: Global Flavors, New Traditions” by Michael Aaron Gardiner (Rizzoli) is an especially timely cookbook. Gardiner also offers recipes that are especially appropriate for Rosh Hashanah. But the book is so inventive and inviting that it has a shelf life that will extend far beyond our present circumstances.

The starting point, of course, is kashrut. “Kosher cuisine is about what can be done within a given set of rules,” the author concedes, but he also insists that “[k]osher food is a living, breathing process, not a museum piece.” Among his other innovations is an awareness of the secular dietary rules that have come to be overlaid on the laws of kashrut in many modern Jewish homes — some of his recipes are especially designed for vegetarians, vegans and gluten-free eaters.

The key word Gardiner uses to define his approach is “fusion,” but he points out that the concept has a long history in Jewish cuisine. “[T]he Jewish people traveled, willingly or otherwise, throughout the world,” he observes. “Forced to adapt the application to those laws to the local ingredients in these new lands, they engaged in a remarkably fertile exchange of culinary ideas with their hosts.”

It was always a two-way transaction. The Polish stuffed cabbage rolls called golabki are inspired by holishkes, “a dish prepared by their Jewish neighbors.” And Gardiner’s recipe for holishkes is itself a fusion of both Sephardic and Ashkenazi culinary traditions, a “combination of the sweet, evocative warming flavors from the cardamom and the creaminess and bitter notes of the tahini with the savory chicken and chicken parts inside the stuffed cabbage.” To his recipe he adds a dash of history — Gardiner honors the Jerusalem mixed grill, “a quintessential Israeli dish [that] was created in the shadow of Jerusalem’s Machane Yehuda Market no earlier than the late 1960s.”

Similarly, he argues that the very name of gazpacho, the iconic cold soup from Spain, is rooted in Hebrew word gazaz, which means “to break into pieces.” The dish itself dates back to the Moors, and he explains that “[m]uch of Sephardic cuisine began it life as Islamic (Moorish) dishes filtered through the laws of kosher.” Gardiner’s list of ingredients for gazpacho pointedly includes “attractive cilantro,” which is used to decorate the dish in the bowl, as do the five tiny dots of cilantro oil that are arranged in a crescent on the surface of the soup. (We learn these fine touches, by the way, from the superb color photographs that accompany all of the recipes.)

As an alternative to gefilte fish for Rosh Hashanah dinner table, Gardiner offers a recipe for oil-poached tuna with curry and chutney, a nod to the Jewish community that has long existed in India and still does in much reduced numbers. “Indeed, Judaism was one of the first — if not the first — foreign religions in India, arriving two millennia ago,” he writes. And he offers a recipe for tzimmes that uses beets, a traditional Rosh Hashanah ingredient, in place of carrots. “It may not look like tzimmes,” he cracks, “but, frankly, that’s a good thing.

The key word Michael Aaron Gardiner uses to define his approach is “fusion,” but he points out that the concept has a long history in Jewish cuisine.

The two main sections of “Modern Kosher” explore what the author calls “Diaspora Food” and “New Israeli Cuisine,” but all of the recipes have been updated and enriched. As an example of how he tweaks a traditional Diaspora dish, he gives us “Roast Chicken With Schmaltz Massage and Le Puy Lentils.” The Israeli dishes are no less innovative, and he points out that two dishes that have come to be regarded as part of Israeli cuisine, shawarma and shakshuka, are, respectively, Lebanese and Tunisian in origin. “And yet the Israeli versions of them aren’t just the old recipes transplanted to Israel,” he writes. “They are reinterpretations and variants on the originals. The living, ever-changing, fusion nature of Jewish cuisine continues.”

Most of “Modern Kosher” is devoted to recipes for various dishes to be served at the table, although Gardiner does not offer dessert recipes, mostly because “that’s not the way I eat.” However, he does provide a section titled “Pantry,” which consists of recipes for stocks, sauces, dressings, herb and spice blends, and other “garnishes, flourishes, and staples,” all of which, he promises, “can take your cooking to another level.” Here the reader will find more surprises, including a recipe for garum, a sauce made with fermented fish that originated in ancient Rome and exists today in Southeast Asian cuisine. “[Y]ou could add it to just about any sauce (or, for that matter, any savory dish) and it will make the dish better and cures what ails you.”

Gardiner, who identifies himself in the book as a Reform Jew, recognizes that not all of his readers keep kosher, and he makes an argument why you did not need to be highly observant to do so. “At the simplest level, if you keep kosher, you’re Jewish,” he explains. “Many — but not all — observant Jews would say it’s also true that if you do not keep kosher, you’re not Jewish.” At the same time, he defines kosher cuisine in an admittedly “non-Jewish” way. “A Jew who keeps kosher cannot simply walk into a supermarket and pull anything he or she wants off the shelf,” he writes. “In that sense, all aspects of eating — even shopping at the supermarket — become part of a surprisingly contemporary and spiritual notion: mindfulness.”

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.