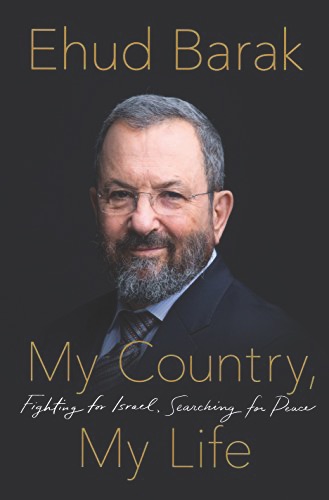

A poignant and chilling story about the 1972 hijacking of a Sabena airliner is told by Ehud Barak in his newly published memoir, “My Country, My Life: Fighting for Israel, Searching for Peace” (St. Martin’s). As commander of the special forces of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) known as Sayeret Maktal, it was Barak’s responsibility to choose the men for the rescue mission. Two brothers, Yoni and Bibi, volunteered for the crucial but dangerous assignment.

“We want you to decide,” they said. On that day, Barak chose the younger brother. “Today it’s Bibi,” Barak said. “But Yoni, this is not our last operation. I will make sure you are there the next time.”

Bibi, of course, was Binyamin Netanyahu, and Yoni was his older brother, Yonatan. The retelling of the incident allows us to see the current prime minister of Israel at an early and decisive moment in his long career, a private encounter that only Barak or Netanyahu himself is able to share with us. Beyond that, of course, Barak allows us to witness the tragic irony of the 1972 incident — Yoni was later sent on the rescue mission to Entebbe, where he was fated to be the only Israeli soldier to lose his life.

The same intimacy and irony suffuses all of Barak’s memoir. Barak is not merely writing about history; he was an active participant in the history of Israel as described in “My Country, My Life.” Barak is among the most decorated soldiers in the history of the IDF. Famously, he put on makeup and women’s clothing during a clandestine operation in Beirut to assassinate the Black September terrorists who carried out the slaughter of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. As prime minister of Israel, he sat across the table from Yasser Arafat at the Camp David summit in 2000, coming as close as any Israeli government official so far to achieving a two-state solution. He has known and served with virtually all of the key figures in the history of Israel since he first put on an IDF uniform in 1959, “three months shy of my eighteenth birthday.”

Barak’s memoir often reads like a breathless international thriller or a blood-and-guts war story, and it rings with the kind of authentic and colorful detail that only a first-hand participant can bring to the narrative. I was fascinated to learn, for example, that Barak favored a .22-caliber Beretta pistol to the Uzi machine gun for use in an operation like the storming of a hijacked airliner because the smaller weapon is more practical in confined quarters. And Barak reveals that he came within shooting distance of Arafat during a 1968 military operation in Jordan, but the Palestinian leader was able to escape the field of battle on a motorcycle. Indeed, Barak knows what constitutes an “existential threat” to the State of Israel with more precision than most observers of the Middle East because he has held the weapons of war in his own hands and commanded countless others in battle.

“This book is only partly the story of my life. It’s also about Israel, the country whose birth I had the privilege of witnessing, and with which I’ve shared childhood and adolescence and, now, its increasingly troubled middle age.” — Ehud Barak

“This book is only partly the story of my life,” he explains. “It’s also about Israel, the country whose birth I had the privilege of witnessing, and with which I’ve shared childhood and adolescence and, now, its increasingly troubled middle age. I want not just to chronicle my country’s, or my own, achievements along the way. I am also determined to document the setbacks. The mistakes. Misjudgments. Missed opportunities. And the lessons that we can, and must, learn from them.”

Who is better qualified to assess the policies of the government now headed by Bibi Netanyahu than his former commanding officer? And, while Barak credits “Bibi’s mix of strength, endurance and luck” for his successes as a soldier in the IDF, he is more critical and demanding when it comes to Netanyahu’s statecraft. “My concern is the vision he is peddling, at home and abroad, about Israel, the notion that we are too weak to confront whatever dangers might threaten us,” Barak writes of Netanyahu. “Having spent half my life in the military and nearly a decade as prime minister and defense minister, I’m in a better position than most to know this is nonsense.”

Barak is one advocate of making peace with the Palestinian Arabs who cannot be fairly accused of passivity or pacifism. On the eve of the mission in Beirut, which ended the lives of three high-ranking Palestinian leaders, he explained to the men under his command why it was necessary to do so: “I said that what we were being asked to do in Beirut was not an act of revenge but a preemptive attack, and a deterrent,” he writes. “It was a way of preventing the people we were targeting from unleashing further Munichs, and leaving no doubt in the minds of potential future terrorists that their acts would carry a heavy price.”

As the last member of the Labor Party to serve as prime minister since 2001, Barak also recognizes that he must stand up for a vision of Zionism that was once the official policy of the Israeli government but is not much talked about nowadays.

“Senior right-wing cabinet ministers like Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman and Education Minister Naftali Bennett are committed to establishing a ‘Greater Israel’ with permanent Israeli control over all the West Bank territory we’ve held since the Six-Day War a half century ago,” Barak writes. “That’s bad for the Palestinians, of course. But, just as when I went to Camp David, my overriding concern is what it would mean for Israel. This Greater Israel will unquestionably be larger in terms of territory. Yet it shows every sign of being smaller in other ways — less cohesive, less Jewish, less open and democratic, and more isolated — both internationally and from diaspora Jewish communities — than the state whose embattled beginnings I witnessed as a child seventy years ago.”

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.