Benzion Netanyahu Amos Ben Gershom/GPO via Getty Images)

Benzion Netanyahu Amos Ben Gershom/GPO via Getty Images) In the winter of 1960, Benzion Netanyahu, a persona non-grata in Israeli academia due to his far-right, radical beliefs, stands before students and faculty at a college in upstate New York, giving a lecture that may land him a position in the history department. Ruben Blum, a prospective future colleague (the only Jew among the faculty, therefore assigned to guide Netanyahu around the campus) fidgets in his seat, feeling as though Netanyahu’s eyes are piercing into him, and into his way of life as an assimilated, but not entirely accepted, American Jew.

“This is what I think of America — nothing,” Blum imagines Netanyahu saying. “This is what I think of American Jews — nothing. Your democracy, your inclusivity, your exceptionalism — nothing. Your chances of survival — none at all.” He continues: “Your life here is rich in possessions but poor in spirit, petty and forgettable, with your Frigidaire’s and color TVs, in front of which you can much your instant supper and laugh at a joke and choke, realizing you have traded your birthright away for a bowl of plastic lentils.”

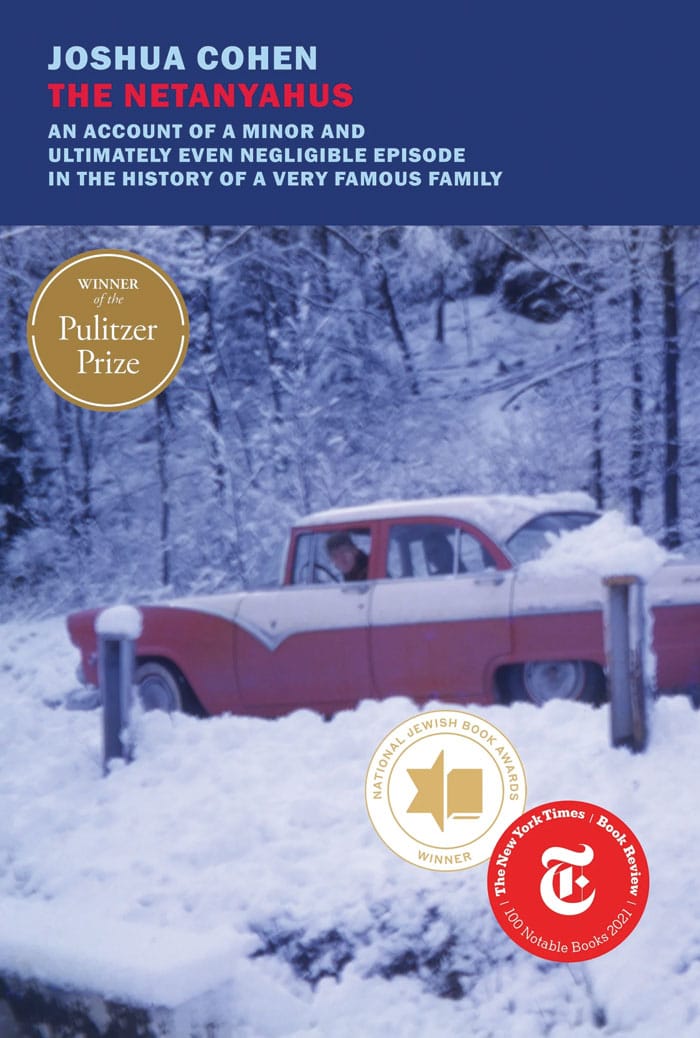

As it happens, Benzion Netanyahu did not really say any of this. This excerpt is taken from Joshua Cohen’s Pulitzer Prize winning 2021 book, “The Netanyahus,” which recounts the fictional tale of Benzion Netanyahu visiting the fictional Corbin College in the winter of 1960, bringing along his three small children, Yoni, Bibi and Iddo, and his neurotic wife to crash the home of the Blums, a Jewish family based roughly on that of the famous Jewish literary critic, Harold Bloom, who did once host Benzion Netanyahu before the family name carried a powerful mystique.

Most analysis of “The Netanyahus” came on the heels of its release, which coincidentally was during a period uncharacteristically without Netanyahu, when Naftali Bennett was Prime Minister of Israel. Yet now that the characters Cohen describes are once again gracing headlines, his book bears previously unexplored insights.

The family carries none of the American niceties and sensibilities that the Blums were born into.

The Netanyahus clash immediately with the Blums. When the Israelis arrive in New York, the three boys, two of which would become two of the most recognizable names in the modern Jewish world, trample around the house, knock over valuables and Yoni, the oldest, “seduces” the Blums’ daughter Judith. Benzion and his wife Tzila are loud, argumentative and presumptuous. The family carries none of the American niceties and sensibilities that the Blums were born into. Not only this, but throughout their time together, Netanyahu insists on embarrassing Blum by pointing out all the ways in which he is being humiliated.

After the interview with the Corbin faculty, Netanyahu grumbles to Blum: “The History Department must decide upon a Jew and so they enlist another Jew for help. Their own Jew. A Jew who is known to them. A Jew they at least partially trust.” He continues, “the court Jew, the protected Jew, the useful Jew to keep in your pocket as a consultant on your taxes … the Elder of the Judenrat who when the Gestapo says, we need to kill one-thousand Jews, he’s the one who picks which one thousand … only partially trusted by both sides.” There are more subtle moments of note as well, such as when Netanyahu eyes Blum’s technicolor television, and remarks, “Sheyn,” beautiful in Yiddish, the language of the Diaspora, of which Benzion and his fellow revisionist Zionists associated with the “weak Jew.” “The Yiddish itself was a dig at me, but the words were oddly admiring,” Blum thinks to himself.

The first time I read “The Netanyahus” upon its release, I understood the theme of the story to be the cleavage between distinct types of Jews, in this case, nationalist, battle-ready Israeli Jews and more cosmopolitan American Jews. Benzion Netanyahu was a disciple of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, known for his uncompromising vision of Jewish sovereignty. Jabotinsky and Netanyahu understood history as a continual siege against the Jewish people, staved off only by military might and attachment to a particular Jewish identity. In contrast, Harold Bloom, on whom Ruben Blum’s character is based, was a definitive product of all the fruits of western civilization. His career spanned from critique of Shakespeare and romanticism to Christianity and aestheticism, prime examples of universalist subjects. It seemed apparent that Cohen’s book was a commentary on what happens when the worlds of Netanyahus and Blooms collide.

The first time I read “The Netanyahus” upon its release, I understood the theme of the story to be the cleavage between distinct types of Jews, in this case, nationalist, battle-ready Israeli Jews and more cosmopolitan American Jews. Benzion Netanyahu was a disciple of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, known for his uncompromising vision of Jewish sovereignty. Jabotinsky and Netanyahu understood history as a continual siege against the Jewish people, staved off only by military might and attachment to a particular Jewish identity. In contrast, Harold Bloom, on whom Ruben Blum’s character is based, was a definitive product of all the fruits of western civilization. His career spanned from critique of Shakespeare and romanticism to Christianity and aestheticism, prime examples of universalist subjects. It seemed apparent that Cohen’s book was a commentary on what happens when the worlds of Netanyahus and Blooms collide.

Yet even Harold Bloom, as with many of even the most internationalist of Jews, still recognized a constant beneath varying layers of identity. When asked about his true beliefs, Bloom is quoted as saying: “I am nothing if not Jewish … I really am a product of Yiddish culture.” It was upon reading this I realized that my original understanding of “The Netanyahus” was incomplete. The conflict in the book was not between Netanyahu and Blum, but rather between Blum and himself.

Long before Netanyahu arrives to torment him, Blum is already deep into the abyss of Jewishness and its corresponding insecurities. He deeply contemplates the religious and cultural differences between his parents and in-laws, he has to force a smile when asked to dress up as Santa Claus for the college Christmas party, and then his daughter Judith, who is insecure about the shape of her nose, devises a plan to fracture it so it will be in need surgery, forcing Blum to think of lies he will tell his coworkers about why his daughter is in the hospital. Benzion Netanyahu didn’t need to bring a storm of Jewish identity-related confusion to Corbin College, for it was already brewing. Netanyahu’s purpose was merely to expose what was, certainly at this time in history, left unexamined: the deeply personal contradictions of American Jewry.

Toward the end of the novel, after a night of chaos between the Blums and the Netanyahus (I won’t spoil the book, but in the end the police are involved), Ruben’s wife Edith, who has also withstood the worst of the Netanyahu anarchy, stands next to him in the snow, watching the Netanyahu car steer off. “Meeting this horrible man and his horrible wife,” she says, “It made me realize I don’t believe in anything anymore and not just that, but I don’t care. I have no beliefs and I’m OK with it; I’m more than okay with it, I’m glad … I’m glad I’m getting older without convictions.” This out-of-place line from Edith is not intended to provide readers with any closure about the theme or the story’s subtext. Rather, it’s written to discomfort us: Plenty of people, but especially Jewish people, are trained to recoil from such ignorance and detachment from the world.

Herein lies the true legacy of Benzion Netanyahu, apart from being the father to a just as polarizing son, whose legacy is still yet to be determined. American Jews revel in a society that promises freedom, yet many still are aware of the dulling of their senses, the numbing agent of conformity. Many American Jews do not need a loudmouthed Israeli to burst their bubble. The war rages on inside regardless.

Blake Flayton is the New Media Director and Columnist for the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.