Mother and daughter stood next to one another at the bimah as part of a jubilant bat mitzvah ceremony. Then, one of them took a deep breath and began to recite verses from that week’s Torah portion.

The speaker was confident, having trained for this moment for two years. And the loving presence of her family and friends, as well as the synagogue’s rabbi and cantor helped put her at ease.

The bat mitzvah girl, incidentally, was 83-year-old Ruth Goldstein.

She stood at the bimah alongside her daughter, Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, at Temple Sinai of Glendale during Shabbat evening services on Friday, June 29 and embraced this sweet rite of passage that she had worked so hard to savor.

I asked Ruth why, at her age, having a bat mitzvah was important to her. Her answer blew me away: “My mother, having grown up in Nazi Germany, didn’t really feel Jewish because she wasn’t allowed to live openly as a Jew, and in some ways, I felt similar. Having this bat mitzvah was in some ways a validation that I am Jewish,” she told me.

To understand Ruth’s journey, one must trace the family lineage to Nazi Germany in the 1930s, where Ruth’s mother, Ilse, had completed medical school and her father, Heinz Lowenstam, had finished his Ph.D. studies. But Heinz wasn’t given his degree for the same reason that he and Ilse weren’t allowed to work in Hitler’s Germany: They were Jews.

In 1937, the couple escaped Germany and entered the United States as refugees by securing an affidavit from Ilse’s brother. They settled in Chicago, where their oldest child, Ruth, was born in 1939. “All of my childhood, I was so grateful that my parents got out of Germany, so I’ve always been grateful to this country,” said Ruth. Tragically, her mother lost 13 relatives in the Holocaust.

But once in America, “the family wanted to leave behind the suffering of the old world,” Ruth’s daughter, Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, told me. That meant that they pursued very little Jewish education for their children. When Ruth was 13, Heinz secured a job at CalTech and the family moved from Chicago to Altadena, Southern California.

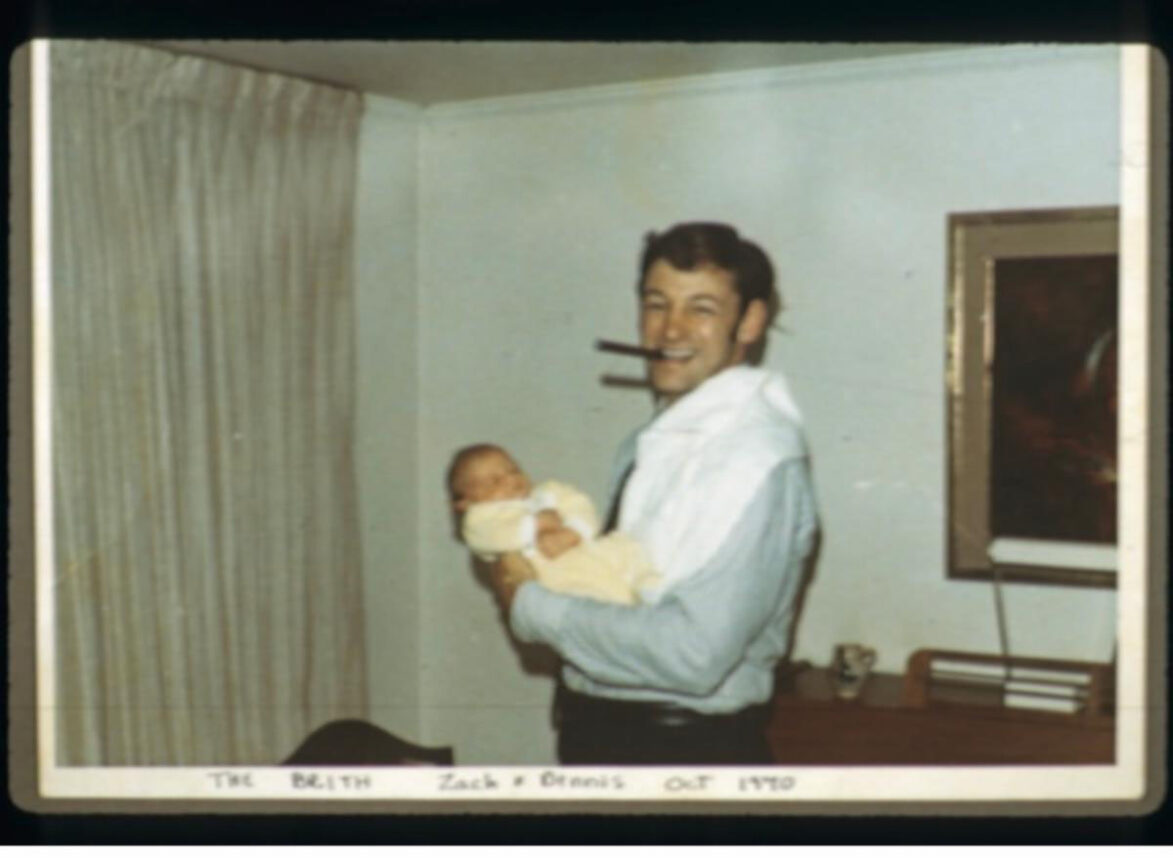

Eight years after moving to Southern California, Ruth, then 21, met a handsome radar astronomer named Richard who grew up in Indianapolis, but had moved to Pasadena to pursue a doctorate from CalTech in Electrical Engineering. Like Ruth, Richard hadn’t grown up in an observant Jewish home, either.

They met on a blind date when they went to see a folk singer perform on Yom Kippur in 1960; they passed by Wilshire Boulevard Temple and saw Jews entering the synagogue for Kol Nidre, “but they weren’t in that mind frame to actually go to services; it wasn’t part of their lives,” said Lisa.

Ruth and Richard were married in 1964. Ruth had always wanted to be a mother, and when Lisa and her two younger brothers Samuel and Joshua grew up, Ruth became a therapist. Despite having been raised secular, Ruth was always interested in spirituality, or as Lisa likes to say, “it was always in her.” At one point, she suggested to Richard that the family join a Unitarian Church, but Richard responded, “We’re Jews. If we go anywhere, let’s go to a synagogue.”

That explains why Lisa, Samuel and Joshua attended Sunday school at Temple Sinai of Glendale, a reform congregation. When a young Lisa arrived home one day and declared, “We learned about Shabbat!” Ruth enthusiastically responded, “Okay, let’s do Shabbat!” Ruth even baked challah, made a hand-embroidered challah cover, and said the prayer over lighting Shabbat candles. The family also recited the kiddush prayer over wine.

“She [Ruth] would have gotten more involved with Judaism earlier, but all of the information you had to know was just overwhelming, and the fact that she didn’t know Hebrew was a huge obstacle,” recalled Lisa. But the Goldstein children were still exposed to Judaism: Ruth told her kids they could choose to have a bar/bat mitzvah, and Lisa and Joshua had theirs at Temple Sinai of Glendale.

“It was really Lisa who brought Judaism into our home,” reflected Ruth. Lisa asked to attend Sunday school and learn another language (it was Ruth who suggested that Lisa learn Hebrew).

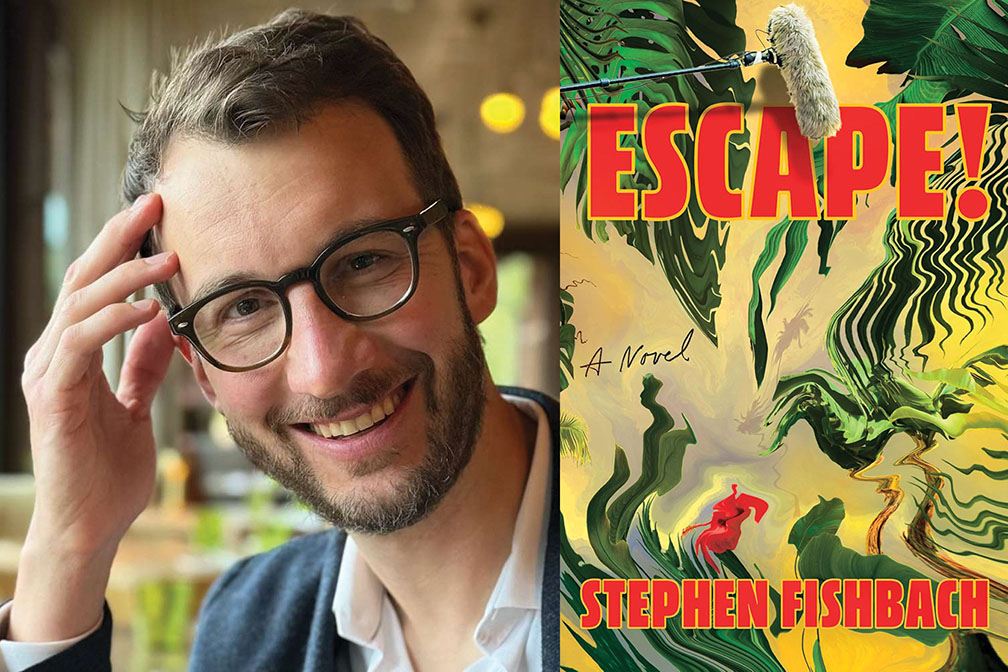

In the years that followed, Lisa became ordained as a rabbi (that’s an amazing story for a separate column), but Ruth didn’t feel entitled to her own Jewish identity because she remained pained by her inability to read Hebrew. When Ruth turned 75, Lisa gave her loving mother a pomegranate-embroidered tallit because she (Ruth) was attending Temple Sinai of Glendale, where both men and women don tallit, frequently, but Ruth responded that she didn’t deserve to wear the tallit because she didn’t read Hebrew.

For decades, Ruth found another outlet for spirituality through hiking in the mountains, and when Lisa turned 40, mother and daughter climbed Mount Kilimanjaro together. “She’s an amazing hiker,” said Lisa. “She beat me up and down that mountain both ways.” Each year, Ruth visits the Grand Canyon; she hikes down the canyon, sleeps overnight and climbs up in the morning. “Hiking is where her spiritual expression came out,” reflected Lisa. “It was more accessible for her.”

As Ruth approached her 83rd birthday, Lisa’s aunt, Susan, reminded the family that in Tehillim (Psalms) 90, Moses declares that the span of human life is 70 years (“The days of our years because of them are seventy years”). Perhaps Ruth could experience her bat mitzvah at age 83 (adding 70 and the traditional 13), suggested Susan, citing a Jewish custom for some older adults.

But the thought of learning enough Hebrew to chant Torah verses and have a bat mitzvah ceremony was too daunting for Ruth, and she rejected the idea.

One week later, Ruth called Lisa in Manhattan and asked, “You think I could do it?” Lisa was thrilled. “Let’s do it!” she cried. That was in 2020.

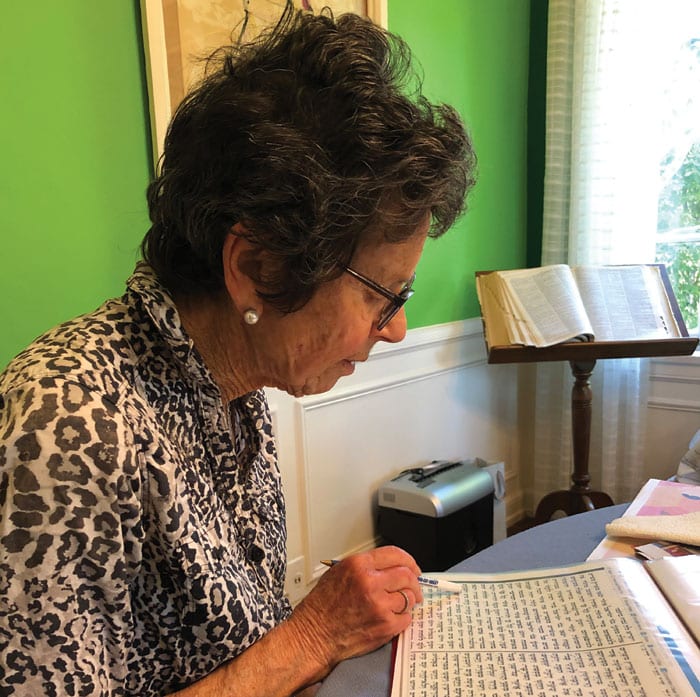

Over the next two years, Ruth and Lisa studied Hebrew together twice a week via telephone; Lisa even bought Ruth a helpful series of textbooks called “Aleph Isn’t Tough.” Ever curious and passionate, Ruth didn’t simply didn’t want to learn how to decode Hebrew letter by letter; she wanted to truly understand the meaning behind each word.

“I didn’t even know the [Hebrew] alphabet,” said Ruth. “There were times when I would get discouraged and Lisa would say, ‘That’s natural. Just study a little more and you’ll feel better.’ So I studied one, sometimes two hours a day. Lisa was right. I always felt better.”

I asked Lisa what it was like to teach her mother Hebrew. “It was so tender and sweet, because she cares about it so much and she really, really wants to feel at home in this tradition,” she said. “And it’s hard; it’s hard no matter how old you are. As you get older, it gets harder. This was just so huge for her.”

Together, Ruth and Lisa managed to turn a devastating pandemic into an opportunity to learn and connect, 3,000 miles apart between Ruth’s home in La Cañada and Lisa’s home in Manhattan.

Together, Ruth and Lisa managed to turn a devastating pandemic into an opportunity to learn and connect, 3,000 miles apart between Ruth’s home in La Cañada and Lisa’s home in Manhattan (for Lisa, there’s still a connection in her life with Germany; she lives in what was originally a German Jewish refugee neighborhood nicknamed “Frankfurt on the Hudson”). Lisa even recorded herself chanting verses from Ruth’s Torah portion and sent the recordings to her mother. “Lisa’s a wonderful teacher,” said Ruth, who learned the Hebrew alphabet, as well as basic Hebrew grammar and cantillation.

Ruth also connected with Temple Sinai’s Rabbi Rick Schechter, who helped her plan the bat mitzvah and also prepare a powerful dvar Torah. “That night, we were celebrating Ruth,” Rabbi Schechter told me. “And we were celebrating the deep significance of Torah and Judaism—the transformative role it can play in our lives and in the lives of our families.”

Her parasha (weekly Torah portion) was Parashat Masei, which includes descriptions of the stations of the Israelites’ journey in the wilderness. “I thought about the journey that Moses and Aaron led, and I thought about how my life has been a journey, too,” Ruth told me. “The Israelites escaped bondage; my parents escaped the Nazis in 1937. And I thought about other journeys, including the time that I was 22 and went with my father to Rio, Brazil, to celebrate his parents’ fiftieth wedding anniversary” (Heinz’s parents had also escaped Nazi Germany but weren’t allowed in the U.S. without affidavits, so they resettled in Brazil). Ruth continued, “During that trip, I was so amazed to see that my grandparents still loved each other, and I wanted that for myself.”

True to form, Ruth worked diligently to invest in her relationship with Richard: “I made sure that the goal that I set for myself at 22 became true,” she said. The couple has been married 58 years. Richard, now 95, beamed with pride at Ruth’s bat mitzvah last month.

And he wasn’t the only one. Ruth invited “all kinds of people” to share her jubilant accomplishment, according to Lisa. The guest list included family (one niece flew in from Charlottesville, VA), friends new and old, and of course, friends Ruth has made from decades of hiking.

Most Friday nights since the pandemic began, the synagogue had hosted 15-20 worshippers, according to Ruth. But that night, 100 people gathered at Temple Sinai of Glendale to support Ruth Goldstein.

How did it feel to chant nine verses of a Torah portion and to experience a bat mitzvah at 83? “It was wonderful; I was so grateful,” said Ruth. “I was just overcome. It was almost like the High Holy Days.” Ruth asked Lisa to stand next to her at the bima; it was the same bima where Lisa and Ruth’s youngest son, Joshua, had stood during their respective bat and bar mitzvah ceremonies. To say that the moment embodied a full circle would be an understatement: Decades earlier, when an adolescent Lisa had read in Hebrew from her bat mitzvah parasha at that bima, she had actually paused each recitation to translate the words into English for those listening. Afterward, Ruth said to Lisa, “You should be a rabbi!”

When Ruth finished chanting her verses and delivering her dvar Torah, she was delighted when several attendees told her that they wanted to experience a bar or bat mitzvah as older adults, too. The celebration also included delectable baked goods. Naturally, Ruth and her friends had spent over a month baking and freezing the sweet treats.

“One of the most touching and heartfelt moments was when Ruth passed the Torah through the generations before she marched with it around the sanctuary,” said Rabbi Schechter. Traditionally, grandparents pass the Torah to parents, who pass it to bar/bat mitzvah adolescent.

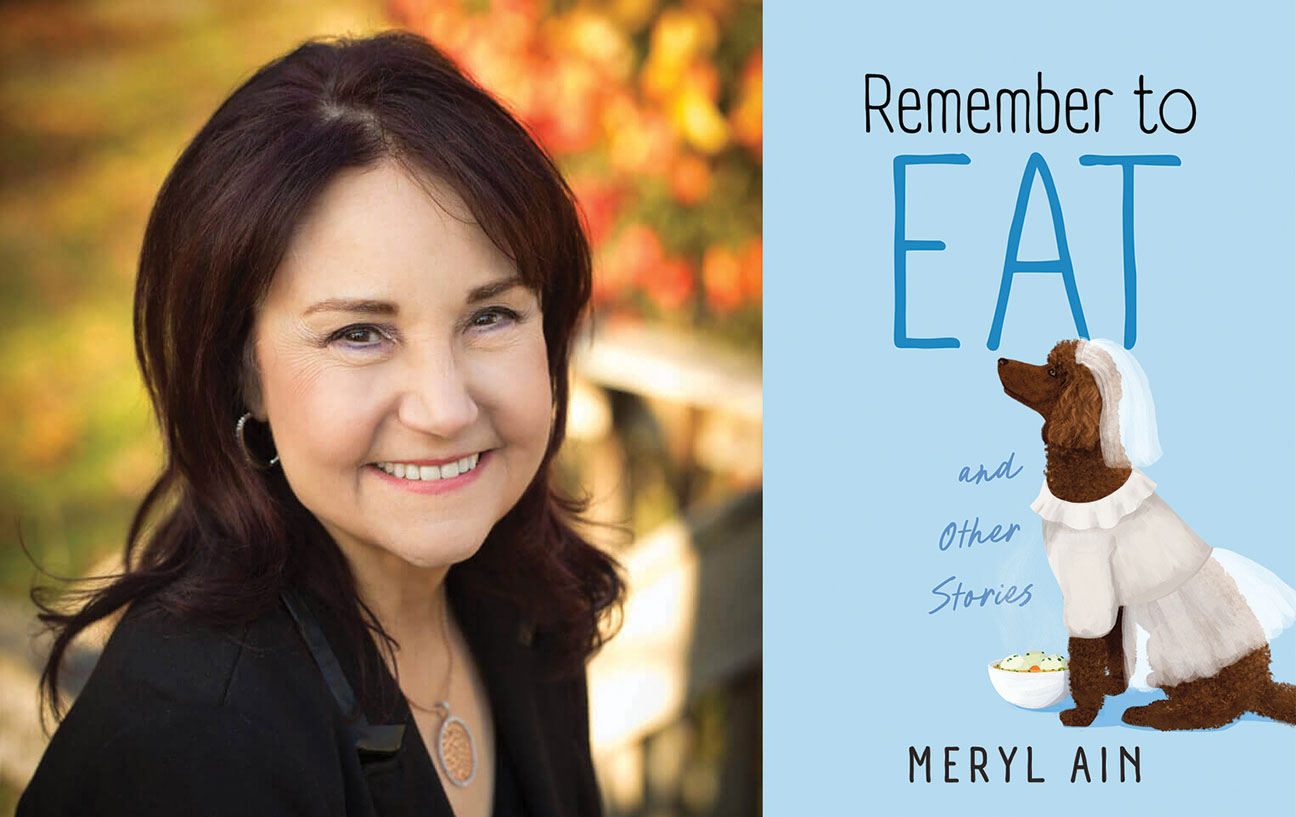

Photo courtesy Lisa Goldstein

But Ruth wanted to do something different: She and Richard passed the Torah to their three children, and they passed it to their two grandchildren who were present. Then, at Ruth’s request, the teenage grandchildren passed the Torah back to their parents, and then they passed it back to their parents, Ruth and Richard. It symbolized “the giving and receiving of love that takes place through the generations, the giving and receiving of Jewish commitment and traditions that passes between family members,” said Rabbi Schechter. “The generations feed each other in a reciprocal relationship.”

Ruth urges Jewish adults to consider a bar/bat mitzvah ceremony, and Rabbi Schechter agrees.

“Learning in Judaism is indeed meant to be lifelong. No matter our age or experience, we can always grow—we can always learn, develop, and enrich our lives and the lives of others. Becoming an adult b’nei mitzvah confirms that we continually have experiences throughout our lives that are sacred—such special moments that are pregnant with meaning and significance.”

I asked Ruth whether after two years of daily Hebrew learning and one very meaningful bat mitzvah ceremony during which she read from Torah, she finally felt Jewish. “Oh, yes,” she said. “Now I feel like I’m Jewish. It’s a real gift.”

Tabby Refael is an award-winning LA-based writer, speaker and civic action activist. Follow her on Twitter @TabbyRefael