I was startled awake from my Shabbat afternoon nap by the sounds of sirens and shouting coming from the Jerusalem street outside the apartment my wife and I were renting for a few weeks during the summer of 2015. Was it a terror attack? An accident?

Any kind of commotion is a magnet for me. I have spent most of my life walking into potentially volatile situations to see how I can help, both in my countermissionary and Jewish outreach work, and in my work as a police chaplain and a reserve law-enforcement officer.

I rushed down six flights of stairs and up the hill to the nearby intersection. Immediately, I saw that this was no terror situation. On one side of Rechov Neviim, just across the street from the Bikur Cholim Hospital, about 150 bearded men dressed in all manner of black coats and hats swayed, chanting one word in a trancelike state.

“Shabbos! Shabbos! Shabbos!” they screamed.

Across the street, about 70 young secular Israelis, dressed in shorts and tank tops, brandished signs and chanted slogans protesting the infringement on their rights to use public transportation, shop or eat in restaurants on Saturdays.

It turned out, the protestors were regulars, fighting over how Shabbat would be observed in the public spaces of Israel — a battle that ratcheted up again recently when the Supreme Court ruled that Tel Aviv grocery stores could open on Shabbat.

In 1947, David Ben-Gurion came to an agreement with Orthodox rabbis that stipulated that public transportation would be closed on Shabbat, and municipalities could legislate which businesses could open. In Jerusalem, nearly all businesses are closed on Shabbat, and there are frequent and loud demonstrations over the status quo.

Since I founded Jews for Judaism 32 years ago, to counter deceptive proselytizing efforts targeting Jews, I have learned that what pulls people into cults is the warmth, love and community they offer. And what pulls people back to Judaism is the warmth, love and community we can offer. Coercion, manipulation and protests don’t move any minds or spirits.

So that Shabbat afternoon, I approached the Charedi side of the protest.

“Gut Shabbos,” I said to them, speaking in Hebrew and Yiddish. “Instead of chanting, ‘Shabbos,’ why don’t you say ‘Gut Shabbos,’ or ‘Shabbat Shalom?’ Show the chilonim [secular Israelis] what is beautiful about Shabbos.”

As if I didn’t exist, this extremist fringe of the Charedi community continued their mantra.

So I walked over to the secular side.

“Shabbat Shalom!” I screamed above the din. “Anyone who wants to see what Shabbat is really about please follow me to my apartment, a half a block away, for some good food and conversation. We’ll enjoy Shabbat, instead of standing here fighting about it.”

A few minutes later, I began to walk down the hill to my apartment. I turned around, and to my surprise about a dozen young secular Israelis were following me.

“Dvora,” I announced to my wife as we walked in, “we’re going to need a few more chairs, and all the food we have.”

I have spent most of my life walking into potentially volatile situations to see how I can help.

Dvora was unfazed, since we have hosted hundreds of people at our Shabbat table over the years, from Jewish Hari Krishnas to Jews of all ages eager to learn about their heritage. We pulled out pita, hummus, Moroccan fish, salads, drinks, chocolate rugelach — whatever we had. I also brought out a few bottles of good scotch.

The conversation flowed, as did the l’chaims. I shared some of my crazy stories about the people I’ve encountered and helped — religious and nonreligious, Jews and non-Jews. I wanted them to see that Judaism is about loving every Jew, and indeed, every human being.

A few hours later, long after the demonstration on the street had dispersed, we walked our guests out. They thanked us, saying they now had a new impression of Orthodox Jews and of Shabbat.

When I see the violent protests going on in Israel today, most recently related to Charedim being drafted into the military and protests over train construction on Shabbat, I know that anger and force won’t turn hearts and minds. And while these complicated issues won’t be solved over a spontaneous l’chaim, either, I know — given the mission of Judaism to make other lives safe, better and more meaningful — that it’s a step in the right direction.

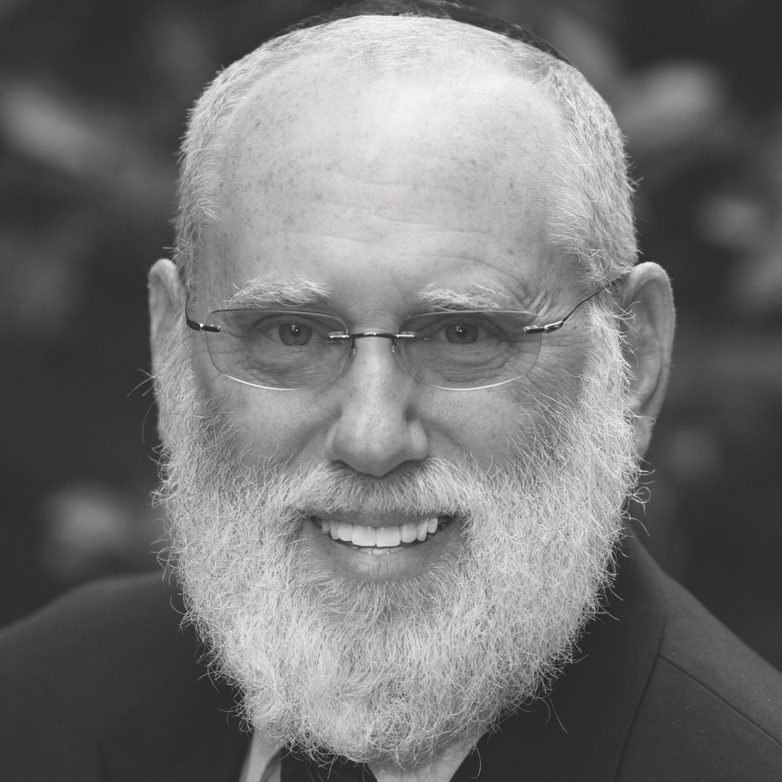

Rabbi Bentzion Kravitz resides in Los Angeles and is the founder of Jews for Judaism.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.