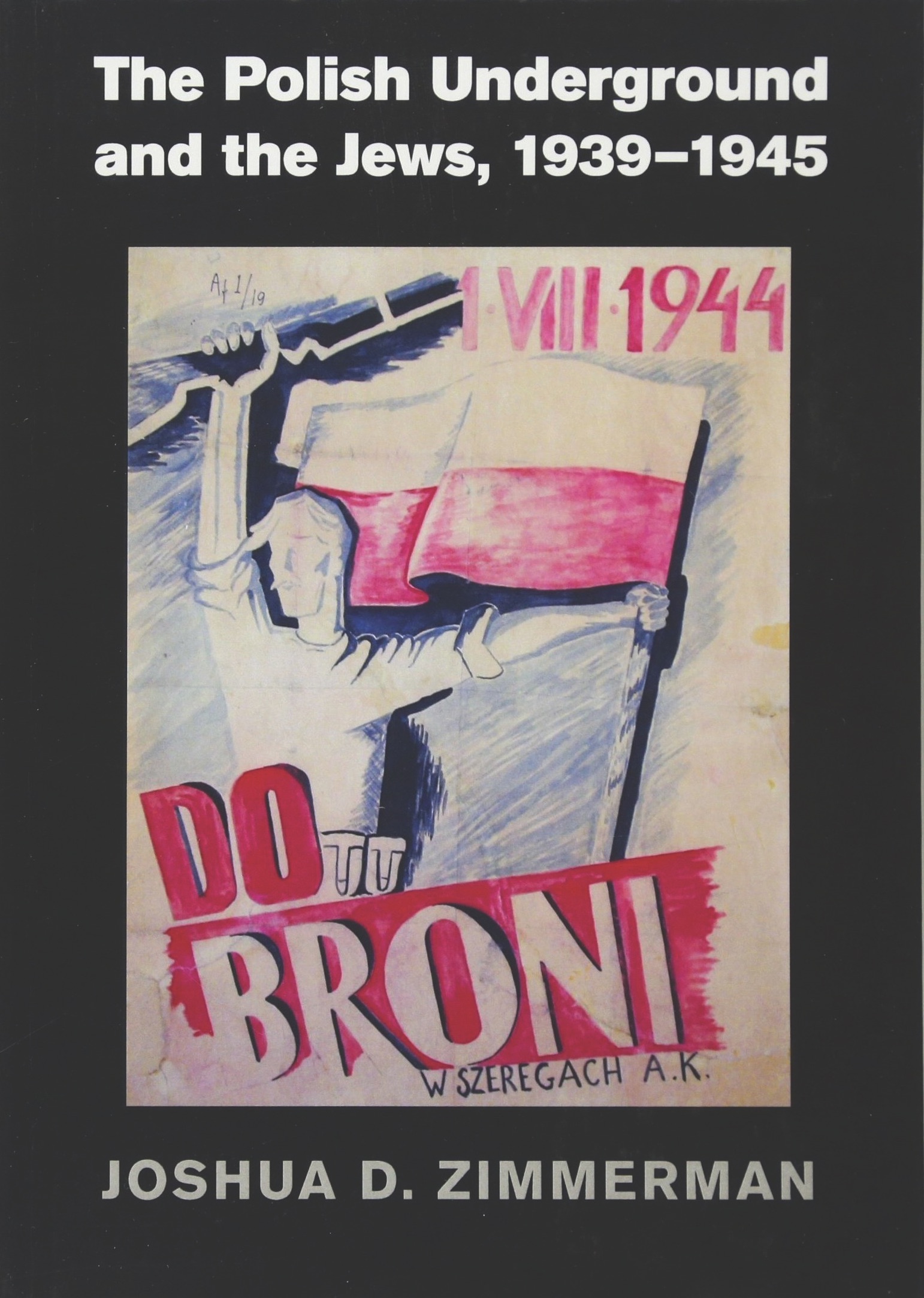

Some books are timely, others are useful and still others are good. Joshua D. Zimmerman’s “The Polish Underground and the Jews 1939-1945” (Cambridge University Press) is all three.

What makes it timely is recently passed Polish law that criminalizes any mention of Poles “being responsible or complicit in the Nazi crimes committed by the Third German Reich.” The ultra-nationalist Law and Justice Party government is committed to advancing a Polish-centric agenda, openly pushing to rewrite the country’s history to stress Polish heroism and obliterate Polish guilt.

Zimmerman’s meticulously researched, scrupulously balanced and comprehensively written work will create much anguish for those attempting to rewrite that history. For few have done the work to examine all the records and fewer still will balance the evidence without bending it to arrive at seemingly irrefutable conclusions.

Polish nationalistic historians won’t be the only ones upset by his findings. Jewish historians who seek simple answers and don’t want to deal with the complications of the Polish situation will find his balance disconcerting. The story is complicated and Zimmerman does not shy away from presenting the complications clearly, unraveling the puzzle and reassembling its parts so that the reader can understand the complexities.

Among serious scholars, it is axiomatic that good scholarship drives out bad scholarship. And for good scholarship there is no substitute for serious homework, going to archives, reviewing the evidence, reading memoirs and listening to testimony, and weighing all this material to present a coherent picture of the whole.

Zimmerman’s meticulously researched work will create much anguish for those attempting to rewrite that history.

Some scholars do a marvelous job of presenting an overarching theory and then leave the reader and researcher wanting for particular evidence or indications why contrary conclusions don’t hold up. Other scholars drown the reader in detail but miss the larger perspective. Zimmerman does neither; attention to detail substantiates the general picture he offers and illustrates what he is trying to show. One must appreciate such detail and value his major substantive conclusions.

One of them is that the Polish Underground’s attitude toward the Jews reflected the political views of its major constituent bodies, military officers and individuals in pre-war Poland. Those who were open to a more pluralistic Polish society that accepted minorities as part of the landscape of Poland had a radically different attitude toward the Jews than those whose orientations were more nationalistic in the most narrow sense of the term. I suspect that what was true then is still true today.

The attitude toward the Jews was not only a mirror of pre-war attitudes but depended on geography and on the progress of the war. Why geography? Attitudes in the East (the territories first occupied by the Soviet Union after Sept. 17, 1939) were far different than in territories solely occupied by Germany. Poles in the East did not appreciate why Jews were far more welcoming to Soviet occupation when the alternative was German occupation. They were far more ready to identify Jews with Communism, far less willing to understand the impact that Communism had on individual Jews — capitalists and merchants — and on Judaism while also protecting Jews in Soviet-occupied sectors from ghettoization and vilification by German anti-Semitism.

Why timing and the progress of the war? The Polish Underground’s attitude toward the Jews also underwent a significant shift when it appeared that the Soviet Union, rather than the Allies, would liberate Poland from Nazi Germany. The Polish Underground opposed Nazi Germany but it also properly feared that liberation by the Soviet Union would be a pretext to Soviet domination, not Polish national independence, and certainly not the post-World War I Poland that the Polish people had enjoyed.

How was the attitude toward the Jews affected by the unfolding of the world war and the war against the Jews? It shifted as the larger fate of Polish Jews under German occupation became clear. As the scope, discipline and progress of the killing unfolded, Poles’ reaction toward the Jews changed. Those who would argue that even Poles who resisted German occupation were not unhappy about Germany’s eliminating Jews from Poland — all the while feeling revolted by the means — will find much in Zimmerman’s work to substantiate their views. But he also brings evidence that as the murder of the Jews became more widely appreciated, some Poles became more sympathetic toward their disappearing neighbors.

While the content of this work is exceedingly disquieting, the work of the historian is deeply satisfying.

Why timing? The attitude toward Jews, and especially toward arming Jews, changed after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943 and the gesture of the ghetto resistance to fly a Polish flag and to proclaim their fight — for our freedom and yours. Zimmerman’s chapters on the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Warsaw Uprising on 1944 are comprehensive and insightful. The Polish government-in-exile faced different pressure than the army in the field. The participation of Jewish representatives in the governing council strengthened the support for the Jews from within the government and the desperate need of the Polish government-in-exile for Allied support, and its physical location in Churchill’s London rather than Stalin’s Moscow made it imperative that they portray their struggle for Poland as a democratic one.

The Polish Underground depended on the dedication of its participants to the cause of the Polish nation and their antipathy toward the occupation. Therefore, it was not as willing to define the meaning of “Polish nation.” It did not want to say aloud that Jews might again be considered second-class citizens and not quite part of the Polish nation, even though they were citizens of the Polish state.

Zimmerman is careful to consider individual responsibility and not just general policy. Officers lead their soldiers, men and women in this case, and they set standards for them of what is acceptable and not acceptable, of what is expected and not expected. Some are motivated by ideology and some by the camaraderie of battle, the ties that bind soldiers to one another. Because he has read memoirs extensively and reviewed testimony carefully, Zimmerman is able to show how the attitudes of individual officers and soldiers shaped the attitude of the Underground to the Jews and determined the fate of individual Jews.

Some will read Zimmerman’s book selectively. For example, he devotes an entire section to the institutional efforts of the Polish underground toward the Jews. The behavior and the values of Zegotta — the clandestine wartime organization dedicated to rescuing Jewish children — are admirable. And he recounts the heroic efforts of couriers, especially Jan Karski, who secretly brought Jewish communiques to the West. Yet he also details craven collaboration and institutional efforts that intensified the risk to Jews and facilitated their demise. Both were present in wartime Poland, and the current government’s effort to eliminate all mention of the latter will force historians outside of Poland to question whether a depiction of the heroic Poles alone is credible.

The publications of the Polish Underground and not just its reports to the government-in-exile give a real-time understanding of what was known about the Jews’ fate — and when and by whom. It makes more urgent the English language publication of these bulletins, which currently are available only in Polish.

Zimmerman has set a standard of comprehensiveness, excellence, meticulousness and balance. While the content of this work is exceedingly disquieting, the work of the historian is deeply satisfying.

Michael Berenbaum is director of the Sigi Ziering Institute: Exploring the Ethical and Religious Implications of the Holocaust and a professor of Jewish Studies at American Jewish University. For the past decade, he has taught the Holocaust to teachers at Jagiellonian University in Poland.