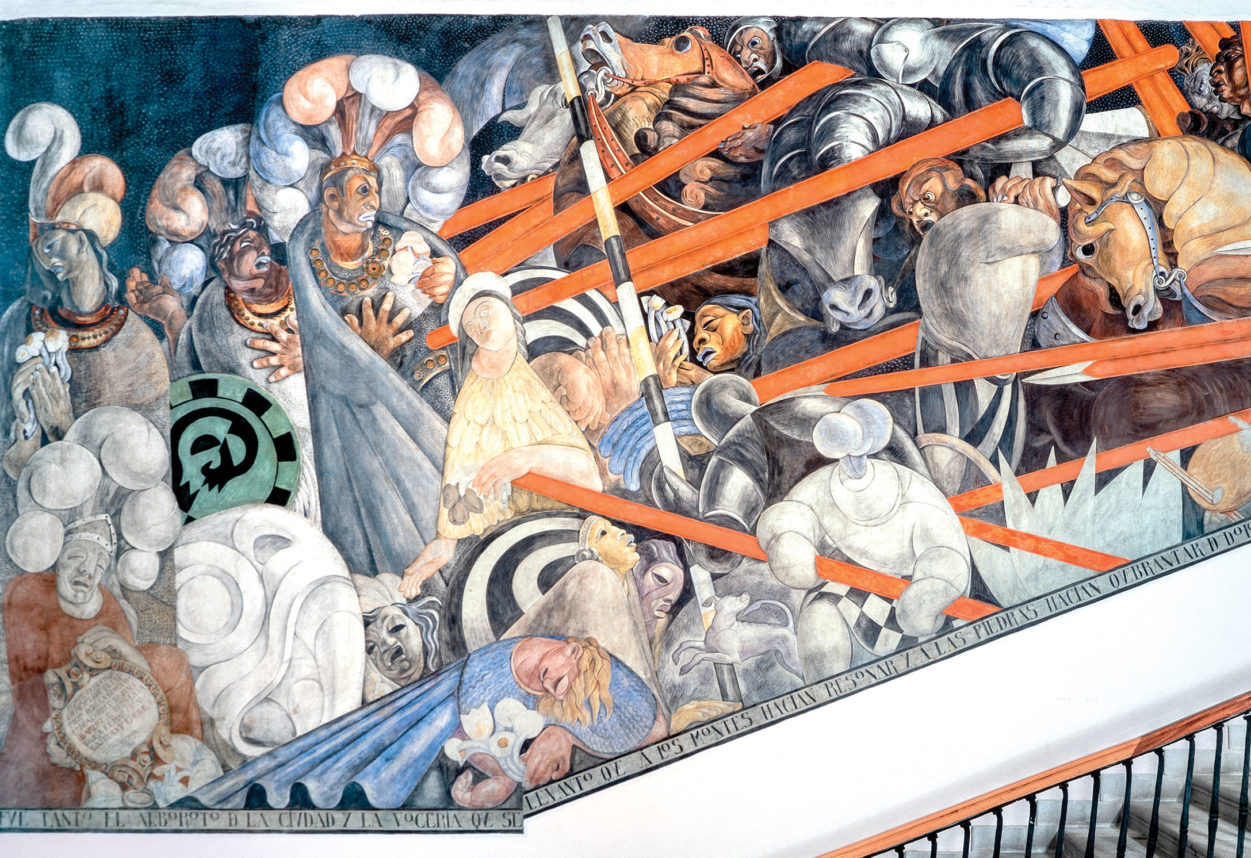

Painting by Anita Brenner.

Painting by Anita Brenner. Anita Brenner might be the most noteworthy 20th-century cultural figure you’ve never heard of but that’s about to change. An exhibition about her, “Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner’s Mexico,” will introduce Skirball Cultural Center visitors to the life and times of a major personality in Mexican art of the last century.

The show opens on Sept. 14 and runs through Feb. 25.

Born in Aguascalientes, Mexico, in 1905 to Latvian-Jewish immigrants, Brenner was a key figure in the Mexican art world of the 1920s and 1930s. She was not a painter or sculptor, but she wrote extensively about Mexico’s art and artists — many of whom were close friends of hers — at a time when their art was not well-known. In fact, Brenner coined the phrase “Mexican renaissance” when referring to the innovative Mexican art currents of the 1920s.

Her adventurous life was painted in colors as bold as the art and artists she wrote about and loved. Her book “Idols Behind Altars,” published in 1929 when she was just 24, was instrumental in publicizing the work of artists in her social/political/cultural circle, including Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, Edward Weston and Jean Charlot.

Like her friends, she was a leftist bohemian who championed indigenous art and culture. The thrust of “Idols Behind Altars” is that if you (metaphorically) look behind Christian altars, you will find traces of the pre-Columbian period, and that the roots of subsequent Mexican art can be seen in the crafts and designs of native civilizations before the Spanish conquest.

Because she was raised in Texas as well as Mexico, Brenner was bilingual, and her interests and published writings — almost always in English — were stunningly wide-ranging. Among other topics, she wrote about what life was like for Jews in Mexico, emphasizing that Jewish immigration to Mexico was good for Jews and good for Mexico. The title of the show, “Another Promised Land,” is taken from a published article she wrote when she was 19.

As a young woman with no college degree, Brenner went to New York and impressed Franz Boas, a prominent anthropologist who had pioneered the idea of cultural relativism. Boas took her on as a student in anthropology at Columbia University, where she received a doctorate five years later.

In the 1930s, Brenner was a freelance foreign correspondent, covering the Spanish Civil War and sending more than 40 dispatches to several publications. In 1943, her book “The Wind that Swept Mexico,” illuminated the Mexican Revolution’s historical context in clear and accessible language. She also wrote children’s books based on Mexican folk tales — illustrated by Jean Charlot, a former beau who remained a lifelong friend and collaborator — and countless travel pieces, trying to promote U.S. tourism to Mexico.

And, by the way, Brenner did all this while raising children. At Columbia, studying with Boas, she met and later married David Glusker, a Jewish physician from Brooklyn, and they had a daughter and a son.

In late 1936, when Leon Trotsky was looking for refuge after his exile from the Soviet Union, Brenner wrote to her friend Diego Rivera, by then Mexico’s most famous artist, asking him to convince Mexico’s president, Lázaro Cárdenas, to grant Trotsky asylum. Exile in Mexico, of course, did not turn out well for Trotsky — he was assassinated in 1940 by a supporter of Joseph Stalin — but at least Brenner tried to help.

“Another Promised Land” has five sections. The first, “A Jewish Girl of Mexico,” traces Brenner’s background and early years and how her parents came to settle in Aguascalientes before she was born.

Laura Mart, a Skirball curator who worked on the exhibition, said Brenner’s parents “didn’t really understand what it meant to be Jewish, so [Anita] had a tough time discovering her Jewish identity when the family was living in Mexico, but it was something she wanted to puzzle out: what it means to be Jewish.”

Because of the turmoil from the Mexican Revolution, the Brenner family moved to Texas when Anita was 11. “In Texas, she was the object of discrimination, first for being Jewish, but also for being Mexican,” Mart said. “That experience led her to want to promote good relations between people, not just between Jews and non-Jews, but also between Mexico and the United States.”

The show’s second section covers Brenner’s impact on art. “Idols Behind Altars” is illustrated with Mexican art — photos of the artwork were taken by renowned photographers Weston and Tina Modotti. The book’s text and illustrations also influenced famed Russian director Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished film, “Que Viva Mexico!” Still shots from the film are in the exhibition.

Other sections of the exhibition deal with Brenner’s political and travel writing and her return to the Aguascalientes ranch of her childhood, where, in the late 1960s, she became an environmental activist and turned the ranch into a kibbutz-like farm.

“The vision of Anita Brenner and the cultural environment in which she was formed in the early 20th century in Mexico was based on the idea that art is transformative in personal, political and cultural terms,” said the exhibition’s guest curator Karen Cordero, a professor of Latin-American art, based in Mexico City.

Brenner firmly believed art should be admired for its beauty, but that it could also affect people deeply and change their views of the world. “That’s always an important thing to keep in mind,” Cordero said. “She was interested in the symbolic, emotional, even mystical qualities of art.”

Mart said a theme that runs through all of Brenner’s writings is “bridge-building.”

is part of the exhibition “Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner’s Mexico” at the Skirball Cultural Center.

“The reason we decided to do this exhibition about Anita Brenner is that we see her as someone who spent her life building bridges,” Mart said. “And there are a lot of different ways you can do that. She chose art and culture as ways of promoting understanding and respect of Mexico.”

“Through all her work,” Mart added, “Brenner was saying: [Mexico] is a place of rich culture, rich heritage. And at the time she did this, there wasn’t a lot of information about Mexico in the U.S., so she helped change the conversation. … She was speaking to an American public who didn’t have a lot of contact with people from Mexico, and she was really the bridge between Mexico and the U.S., promoting goodwill and neighborly responsibility between the countries.”

“Take from that what you will,” Mart added, “given the current political context.”

“Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner’s Mexico” will be at the Skirball Cultural Center from Sept. 14 through Feb. 25, part of the community-wide initiative Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, an exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Southern California, organized and funded by the Getty Foundation.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.