Israel has no reason to take credit for the sudden dramatic fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria. It shouldn’t create the impression that what happened — “a direct result of the strikes we inflicted on Iran and Hezbollah” — is the implementation of an Israeli plan. Israel did not initiate, support, or show particular interest in Assad’s overthrow. In fact, if Israeli leaders had a button to press that would topple Assad, and choosing not to press it would keep him in power, it is entirely plausible to suspect they wouldn’t press it. This isn’t an accusation; it’s a realistic appraisal of what likely would have occurred. The leaders probably wouldn’t have pressed that button, because there is no certainty that a Syria without Assad will be better for Israel. Therefore, all celebrations are retrospective. We’ve stumbled into the party and decided to partake of the free wine.

Indeed, the turn of events in Syria came, in part, due to other processes in the region. Israel’s strikes on Hezbollah certainly contributed to it. But so did the fact that Russia is too busy in Ukraine, which has nothing to do with Israel. And so did the election of Donald Trump as U.S. President, which required Iran to tread cautiously, and that too has nothing to do with Israel. And so did pure luck, which always plays a role in surprise attacks of the type we saw in Syria. That no one predicted the Syrian army’s collapse is almost trivial: It was unexpected. Nothing that happened in Syria in recent years suggested such a rapid event could occur.

If Israel wants to celebrate the fall of Assad for domestic political reasons, or boost its deterrence, or just to feel good — let it celebrate. As long as it doesn’t start believing in its own celebrations. Did Iran suffer another blow? Absolutely. Is that a reason to party? Here the answer gets complicated. Yes, if it leads Iran to reconsider its reckless behavior in the region. No, if it leads Iran to a decision to accelerate its nuclear program. A defeated enemy is one to celebrate over. A wounded enemy is a dangerous one. A wounded Iran, after Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria, might feel it needs to issue a resounding response. If that happens, Assad’s fall will be just a detail in a much more significant development.

A defeated enemy is one to celebrate over. A wounded enemy is a dangerous one. A wounded Iran, after Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria, might feel it needs to issue a resounding response. If that happens, Assad’s fall will be just a detail in a much more significant development.

Besides, whether Iran was hit is not the only question that determines if celebration is due. Alongside it stands the question of the day after in Syria. One possibility: a functioning, orderly state under Sunni control. This is the convenient option that seems less likely, at least in the short term.

Another possibility: a functioning but very hostile and extreme state. A state looking for conflict. That means more war, on a border that was mostly quiet. A third possibility, perhaps the most likely based on past experience: chaos, factional warfare, the absence of central authority. A Libyan scenario. An Iraqi scenario. A Somali scenario. A Lebanese scenario. A Yemeni scenario. In such a case, Israel will need to ensure only one thing – that the chaos does not spill over into its territory. Easy to say, not always easy to do. And this scenario might be compounded by the potential destabilization of the Syrian-Jordanian border, or the westward advance of forces through the Syrian-Iraqi border, among other unpleasant surprises.

And here’s another half-concern: The Turks have grown stronger. This is not good news. True, Turkey is not a bitter and dangerous enemy like Iran, but it is also not in Israel’s interest for Turkey to grow stronger. Its potential influence inside Syria brings it closer to Israel’s border. Recent experience shows that the Turks have no difficulty supporting violent, extremist groups like Hamas in Gaza.

The conclusion is neither pessimistic nor optimistic. It is cautious. Something Israel had nothing to do with happened in the Middle East. A murderous dictator suddenly fell from power. One can rejoice that this is the fate of dictators. One can simultaneously note that this particular dictator held on for many years, following his father who also lasted many years. The average tenure of a Roman emperor was about a decade. Bashar al-Assad was the Caesar of Syria for almost a quarter century. Longer than Tiberius. Longer than Hadrian. Longer than Marcus Aurelius. It is possible that after him, a long civil war will arise, then a new Caesar will emerge, and a new dynasty will begin. It is possible that after him, there will be no more Syria. Israel has some ability to influence the outcome, but it will be limited.

Just as it failed to engineer Lebanon, the Palestinian Authority, or Gaza, Israel will not be able to reengineer Syria. But it can still celebrate. One must hope that it can.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

When IDF spokesman Daniel Hagari criticized proposed legislation protecting intel leakers, I wrote this:

The IDF spokesman was rightly reprimanded by the IDF Chief of Staff. An IDF spokesman should not publicly criticize legislative proposals … [but] he was treated as if he had set some unprecedented historical precedent. Of course, this is not the case. The spokesman did what Israeli officers have been doing since the establishment of the state… The IDF may not be a “small and wise army,” but it is certainly a small and talkative one. This has several significant drawbacks … this also has advantages and substantial reasons. The IDF is not a professional mercenary army. Its symbiosis with Israeli society is embedded in its culture. It is an army of the people in a substantive sense. And this is not necessarily a bad thing.

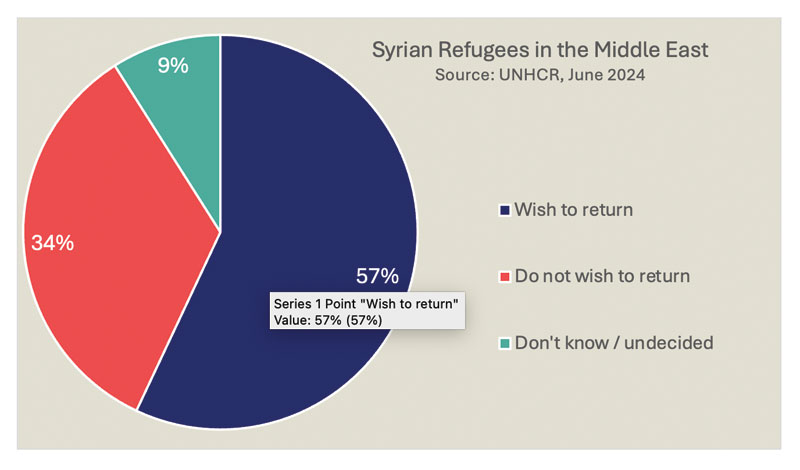

A week’s numbers

Circumstances changed. Will attitudes change?

A reader’s response

Noah Slutzky writes: “I was appalled to read your last week’s article on [‘Voluntary Migration’ in] Gaza. A Jewish State must be Jewishly ethical.” My response: If only we agreed on the meaning of “Jewishly ethical” life would be simpler.

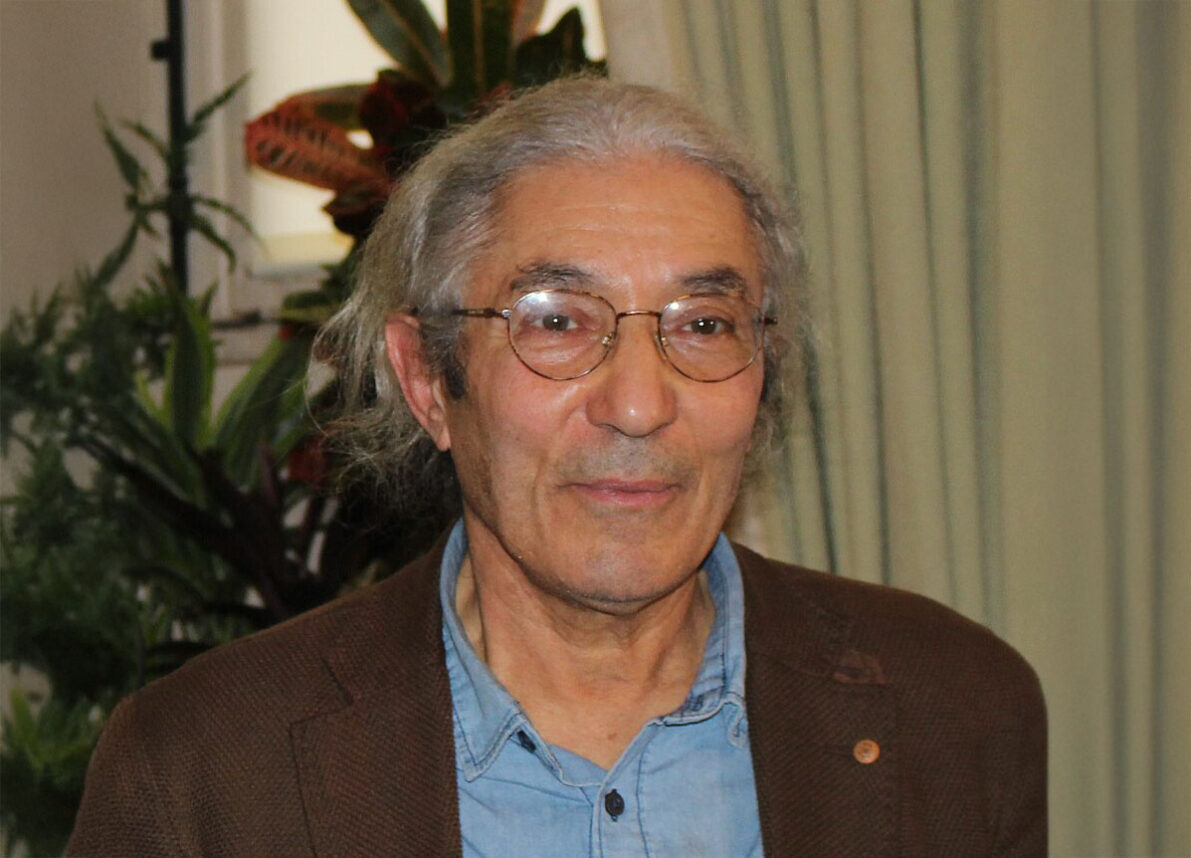

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.