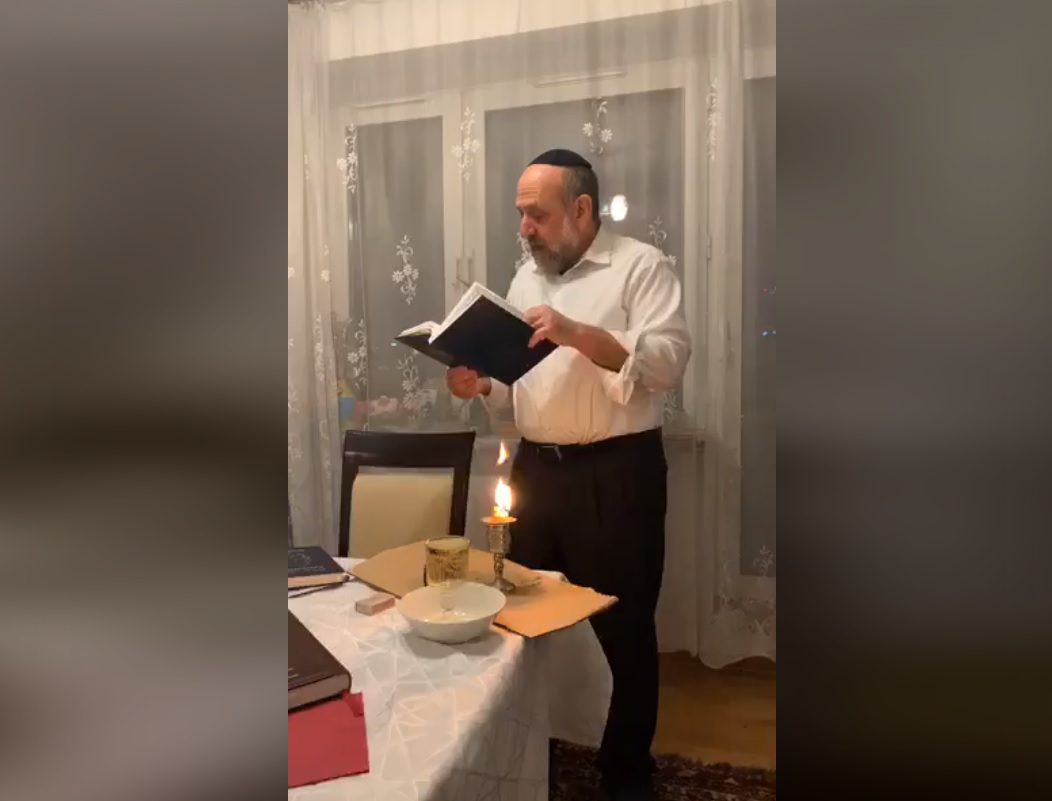

Staff and volunteers with the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) distribute food packages to the Jewish community in Kishinev, Moldova. Credit: Courtesy.

Staff and volunteers with the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) distribute food packages to the Jewish community in Kishinev, Moldova. Credit: Courtesy. BY SEAN SAVAGE

While the coronavirus pandemic showing no signs of slowly down globally, most of Europe appears to be heading in the right direction with cases dropping across the continent and economies either starting to or in the midst of reopening. However, unlike its counterparts in Western Europe, many Eastern European countries, with the exception of Russia, were largely spared the worst of the pandemic thus far.

In Eastern Europe, it appears that the early shutdown of many countries across the region could have played a role in the virus’s slow spread. As a result, Jewish communities there, although small, have been spared some of the worst effects of the pandemic that their brethren in the West, such as in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, which have seen a very high proportion of its Jewish community die as a result of the virus. While Italy and Spain have been hit the hardest, their Jewish populations are simply smaller—approximately 30,000 and 60,000, respectively.

“It varies from country to country and how quickly they recognized the challenges that were before them. Some acted early on and have control of the situation. Also depends on the level of openness of the government and the accuracy of cases reported,” said Mark Levin, executive vice chairman of the National Coalition Supporting Eurasian Jewry, which mainly serves the Jewish community located in the former Soviet Union.

Levin told JNS that the Jewish communities in these countries largely face the same challenges as the larger population, with some exceptions such as the Jewish population skewing older, and in some countries in the region, more impoverished.

“The impact on the Jewish community mirrors that of the larger population. Depends on the size of the community. We know that there are distinct challenges in each of these countries. What is consistent is a strong community attempt to helping as many people as they can,” he said.

Russia and Ukraine represent the two largest populations, and ones with rabbis and thriving Jewish infrastructure in place (at least, until Russian and rebel troops invaded eastern Ukraine in the summer of 2014), with coronavirus cases increasing daily in Russia, putting it in the top five most affected countries.

“They feel like they are assisting all of the people who need to be helped,” said Levin. “Obviously, it’s easier in Latvia and Lithuania, where the population is below 10,000, than Russian and Ukraine, where the population is in the hundreds of thousands.”

What is especially interesting is that a signification proportion of Jewish life, services, learning opportunities, and holiday and other celebrations are spearheaded by the Chabad-Lubavitch movement—namely, Chassidic rabbis creating religious experiences and involvement for largely secular Jewish communities.

‘Working on programs to engage people after the pandemic’

And then, of course, there’s Poland. Like many other countries in Eastern Europe, it began to shut down non-essential services such as schools, shopping centers, stores and restaurants early in the outbreak. Houses of worship were also severely restricted to only up to five people at a time.

Rabbi Michael Schudrich, the chief rabbi of Poland, told JNS that the Jewish community, similar to the country as a whole, has fared well so far during the pandemic. According to Johns Hopkins University, Poland has 35,146 cases with 1,492 deaths, and as of early July has already opened up its borders to neighboring E.U. countries. Compare that to Russia, which is one of the top five nations with the most COVID-19 cases—as of July 2, some 661,165 reported cases and 9,683 deaths.

“Poland in general has a limited number of infected and dead, although many are all concerned that the worse may still be ahead of us,” he said.

As a result of the restrictions, even as they have been easing up, Schudrich said that he has been conducting classes and other Jewish services online as much as possible, and in accordance with Jewish custom and law.

“All of our classes now take place on Zoom. All of our tefillot [‘prayer,’ three times a day] and Havdalah [after Shabbat on Saturday night] take place on Facebook Live. In addition, I have added three new daily classes [six times a week] on Facebook Live [15 minutes each so that more people would join and it works],” he explained.

Beyond the online courses, he said rabbis throughout the country have also been reaching out to families with young children and the elderly, especially those who may not be able to participate in online services.

“We are starting a daily bedtime story for children told by a different rabbi every night. Our rabbis are also calling all of members just to check up on them to see how they are doing. Our social-work department is in contact with our elderly almost every day to see how they are and how can we help. We are also sending food to their homes,” he said.

Prior to the pandemic, Poland had continued to make international headlines in regards to certain stances on historical references to World War II and the Holocaust. In 2018, the Polish government backed down from its controversial Holocaust Law that sought criminal penalties for any accusing the Polish nation of complicity in the Holocaust. The law was widely condemned by the U.S. Jewish community and Israel, and led to ruffled feathers. Geopolitics between Poland, Russia and Israel prompted Polish President Andrzej Duda to skip Yad Vashem’s Holocaust Forum in Jerusalem marking the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in January of this year after he was not invited to speak.

At the same time, there were also growing concerns over the rise of far-right anti-Semitism in the country.

Schudrich says that despite the pandemic, “we have seen no increase in anti-Semitism in Poland. There were a few instances of anti-Chinese hatred.”

Schudrich said he is focused on the full reopening of the economy and helping those in the Jewish community who have been impacted by the economic fallout from the pandemic.

“No one knows what the long-term effects will be. We are certainly concerned that some of the Jews have lost their jobs, and we need to find ways to help them. There is a concern on how will people react when we can return to ‘normal’ living … how quickly people will be comfortable returning to shul for prayers and for classes,” he said.

“On the other hand, we are now in contact with hundreds of people who were not connected previously. How do we build on this virtual relationship to bring this relationship into a real world contact? We are now working on programs to engage people after the pandemic.”

‘Many elderly without food and medicine’

Poland’s neighbor to the east, Ukraine, has also largely been spared the ravages of the virus thus far. The country has seen 45,887 cases with 1,185 deaths so far.

Rabbi Yaakov Bleich, who serves as chief rabbi of Kyiv and Ukraine, told JNS that his government’s decision to shut the country down early, when there were only a handful of cases, has largely led to success in keeping infections and deaths low (although the country has seen a renewed spike recently).

“This allowed Ukraine to really achieve what many Western countries tried—and that is to flatten the curve. Even though [coronavirus] has been spreading, since the country is basically still on lockdown, it is spreading very slowly and in a relatively controlled way,” he said.

Bleich noted that many of the communities in Ukraine have begun assistance programs to help members of the community, especially the elderly.

“Many families who were working and supporting themselves nicely are now without work. This has caused a tremendous strain on these families,” he explained. “Many elderly are finding themselves without money to buy food and medicine. This is being addressed by local communities. There is an initiative to try and bring together the communities to address this problem along with other issues that may come up during and after the lockdown.”

While Ukraine has also not seen a spike in anti-Semitism, there was an incident in mid-May when a police official in the country’s western city of Kolomyya requested a list of all Jews with addresses and phone numbers. This prompted a large international outcry and an investigation by the national police.

Bleich said he has had a good working relationship with the government during the pandemic.

“We are in touch with the government. There have been a number of Zoom meetings with government officials, especially for religious organizations and groups. This allows them to impart the information that they have to us and allows us to discuss with them the issues facing the religious communities.”

Of course, COVID-19 has come after much of the Jewish community, including its rabbis, moved westwards towards Dnipro (until 2016 known as Dnepropetrovsk, a sister city to the Boston Jewish community) as a result of tensions in heavily Jewish areas closer to the Russian border, including Kiev, Donetsk and Lugansk. In the past six years of a conflict that has ebbed and flowed, many single Jews and families also fled the country to places like Israel and the United States, leaving the elderly in place.

‘Part of a wider circle’

Meanwhile Hungary, home to the third-largest Jewish population in Eastern Europe behind Russia and Ukraine, has largely been spared the worst with 4,166 cases and 587 deaths as of early July.

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, whose Fidesz Party holds a supermajority in the Hungarian parliament, moved early on to grant himself sweeping emergency powers to handle the pandemic. While critics contend that he used the crisis to further erode Hungarian democracy, the country has been able to keep the spread of the virus at bay so far. In late June, as the pandemic situation continued to improve throughout the European Union, the government moved to end Orbán’s emergency powers.

Despite the low infection rates, Chabad Rabbi Slomó Köves, who serves as head of the Jewish Communities Association of Hungary (EMIH), acknowledged that it has been difficult to cope with COVID-19.

“We quickly transformed our physical classrooms where there is social interaction to remote and virtual classrooms. The same has applied for the routine Torah lessons we hold,” he told JNS.

But he said that many in the community have lost their livelihoods due to the strict lockdown.

“Unfortunately, we are still dealing with members of the community who lost their livelihood in one fell swoop and went from being donors to needing support themselves. This has of course given rise to an ongoing necessity for social and mental support, which we are also dedicated to help provide for our community.”

Like other Jewish communities throughout Eastern Europe, the community in Hungary has a large amount of elderly, including Holocaust survivors, who have been particularly vulnerable to the virus, in addition to feeling the affections of isolation from the lockdown.

“It cannot be overly emphasized that our community consists of elderly people, many of whom are Holocaust survivors whose ability to communicate on social-media platforms and other online sources of communication at this time is severely restricted. It is our obligation to continue to care for them and maintain as close contact with them as possible,” he said.

Similar to Jewish leaders in Poland and Ukraine, Köves said he has been in close contact and cooperation with the government. He noted in particular that early on in the pandemic, the government worked closely with Israel to facilitate the repatriation of citizens from each country.

One silver lining Köves noted is that the pandemic has emphasized the value of communal life.

“As a rabbi of an active Jewish community, communal life is no stranger to me given its key role in participatory events and prayers. However, when the coronavirus pandemic broke out, I initially felt a sense of loneliness,” he said.

But as they have produced content online and offer services to the community, many residents who had not been involved previously turned the Jewish community for support.

“We noticed that Jewish residents in the city who are not full members of our community have expressed interest in becoming active as they find themselves in need of support and luckily feel that they are part of a wider circle,” said the rabbi. “I believe the understanding that there is great value to social circles, as well as to communal benefits provided by the Jewish community, are phenomena here to stay.”

‘Identify tech-based solutions to manage loneliness’

Michal Frank, regional director for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s (JDC) former Soviet Union Operation, told JNS that the Jewish communities across the 11 countries in the former Soviet Union (FSU) where they operate were disproportionately affected due to their age and socio-economic status.

“Economically, the Jewish community is impacted like the general population. Our clients, however, are some of the poorest Jews in the world, often living on $2 a day, and the virus-propelled economic downturn hits them very hard. In Ukraine, for example, the cost of basic food stuffs has increased by 60 to 100 percent. In Russia, the ruble has devalued. Our clients are very poor to begin with, and this makes life even more difficult than it was previously, especially as many struggled to make ends meet,” she said.

Nevertheless, JDC said they quickly adapted their responses to the countries they serve.

“We began our response earlier than most other organizations or governmental bodies because we were seeing the impact of the virus on Israel and Jewish communities in the U.S and beyond, and knew we needed to act quickly to safeguard those in our care,” she said.

Indeed, the coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately affected the poor and elderly across the world. For JDC, this meant working with local and national partners to provide life-saving services like food, medicine, home care, basic health care and other relief.

This included expanding the hotlines to all Hesed social-welfare centers, working with JDC volunteers to continue the delivery of food and activity sets, such as special holiday packages for Passover and Shavuot, and deploying digital resources like video calls to seniors. They also partnered with an Israeli firm, TechForGood, to “identify tech-based solutions to manage loneliness and social distancing among seniors; monitor the activities, needs and emergency alerts from elderly; and ensuring efficient management of caregivers.”

Despite the challenges facing the Jewish communities in the FSU, Frank said the pandemic has also opened up new outreach to those they serve.

She specifically cited how digital programming and assistance from young volunteers has created new avenues of assistance and connection that didn’t exist just three months ago.

“We have discovered new opportunities for online community programming that is educational, cultural, as well as a powerful engagement tool. For example, through digital programming, our network of JCCs is seeing previously uninvolved community members joining online activities,” she said.

Additionally, she said they were also surprised by how many elderly Jews embraced technology during this time stuck at home.

“We’ve discovered that our elderly clients are more enthusiastic about and desire these kinds of offerings than we anticipated,” said Frank. “We need to ensure they can have access to technology, working within the challenges in the region regarding Internet and mobile connectivity, and continue to adapt content for their needs.”

“While we hope one day to return to in-person activity,” she continued, “we know that the initial work we have made in adapting to digital content and programming for the wider Jewish community needs to now be.”

While it’s impossible to predict how the pandemic will continue to unfold both globally and within Eastern Europe, Levin said that Jewish organizations operating in the region have been working hard to ensure that the most vulnerable are protected, and that Jewish life continues. “The bottom line is the leadership in all these countries, along with the assistance of international organizations like the JDC, European Jewish Congress, World Jewish Congress, the Jewish agency. They believe they have the situation under control as much as they can control it.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.