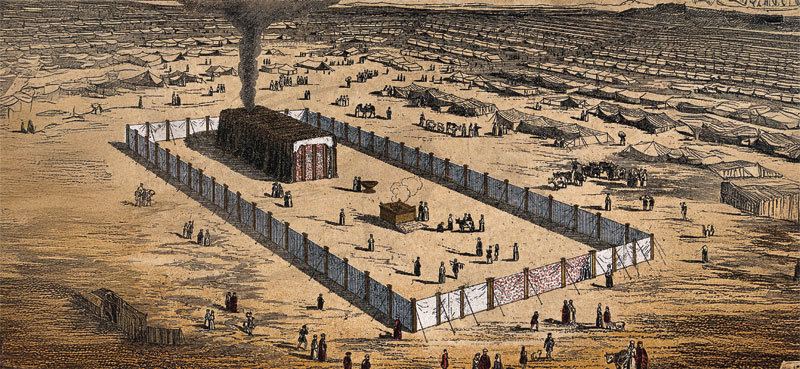

A while ago I gave a Shabbat sermon on “second chances.” I thought it was a fitting message for Parsha Beha’alotcha, which includes the section about Pesach Sheni, the replacement Passover sacrifice. It tells of a group of people who were ritually impure on Pesach and could not offer the sacrifice. Upset by this prospect, they petitioned Moses; the response was that they could offer a replacement Passover sacrifice, the Pesach Sheni, a month later on the 14th of Iyar.

The Pesach Sheni sacrifice is a true second chance and it seemed like the perfect message for that Shabbat, on which we were celebrating a bar mitzvah. At the conclusion of the sermon I turned to the young man and said: “You must understand that even as you take your first steps forward as an adult, the secret to life is that there are always second chances.”

Unfortunately, my sermon didn’t tell the entire story.

Yes, the idea of second chances is central to Judaism. The Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, wrote that “the point of Pesach Sheni is that nothing is ever a lost cause, one can always repair themselves, even those who are distant, even those who are impure … they too can repair themselves.” Repentance is a foundation of Judaism, and the theme of the high holidays; redemption is the theme of Jewish history. Rabbi Akiva, the hero of the Mishnah, was an ignorant shepherd at age 40. Judaism loves second chances.

But there aren’t always second chances.

Hidden in the origin story of the Pesach Sheni are difficult tragedies. The people who petitioned Moses were ritually impure because they had been in contact with a dead body. Rabbi Akiva explains they had been attending to the bodies of Nadav and Avihu, Aaron’s sons who were struck dead by God while bringing an offering in the sanctuary. Nadav and Avihu didn’t have a second chance.

Second chances are less common than we’d like to believe. Pesach is about a people achieving freedom after 400 years of slavery; the last generation went free, but many prior generations died in slavery. They too didn’t get a second chance.

The message of second chances may be perfect for a 13-year-old boy, but it doesn’t sound the same to his grandparents.

It is here that the Pesach Sheni offers another perspective on what a second chance means.

Time seems to jump around in this section of the Torah. (Bamidbar 9:1-14.) The Pesach Sheni narrative takes place during the first month of the second year, while a much earlier passage (1:1) takes place in the second month of the second year. This leads the Talmud to conclude “there is no chronological order in the Torah.” Sometimes events in the Torah are recorded out of order. (It should be pointed out that this passage is the only unquestioned instance of the Torah breaking with a sequential timeline, and according to the Ramban, the only such instance.)

Furthermore, the date for the Pesach Sheni is strange. Why doesn’t it occur a week after Pesach, at the earliest possible opportunity for the people to purify themselves? Instead, Pesach Sheni comes a full month later, on the 14th day of Iyar. It is as if there is an imaginary leap year, and somehow Pesach gets to repeat itself.

Taken together, these elements tell us about a conception of time that is non-linear, an idea that Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik has explored in multiple essays and lectures. He explains that time can be seen purely from the perspective of physics, fragmented and finite, and that what exists in any one moment disappears immediately.

But as part of the human experience, time takes on very different qualities. In our minds, the past and future are ever-present realities; our attitudes toward our past, and what we dream for in the future, define who we are right now. From this perspective, the past is still alive, and the future is already born.

Rabbi Soloveitchik uses this idea to explain the concept of repentance. The past can be a harsh tyrant, with old mistakes holding one in bondage to a life lived in a deterministic nightmare. With repentance, one changes the present by imagining a better future; similarly, by regretting the mistakes of the past and being motivated by those failures, one’s identity is transformed.

Rabbi Soloveitchik extends the concept of nonlinear time to history, in what he calls “unitive time consciousness.” In Judaism, the dream of the future Messianic future is ever-present, and occupies many of the prayers. The past is reexperienced on days like Pesach and Tisha b’Av. The words of the sages who are long gone are studied every day, and “there can be no death … among the company of the sages of tradition.” Past, present, and future are all part of everyday reality; and “in the midst of a fleeting moment, one can experience an ever-enduring eternity.”

The time-shifting associated with the Pesach Sheni offers a profound lesson. Second chances are only possible if one sees time from the perspective of eternity.

Rabbi Yose HaGelili differs with Rabbi Akiva and says that the people who petitioned Moses were impure because they had been carrying Joseph’s coffin. Joseph was the first Jewish exile to Egypt, and before his death, he asked for his bones to be returned to Israel for burial. This is Joseph’s second chance, returning home with his descendants after a long and bitter sojourn. Second chances are not just for the living, because we see history through the lens of eternity.

The second chance you get may not be your own. The generations enslaved could only connect to redemption through their dreams; ultimately, those dreams were lived out by their descendants. But that final redemption belongs to all previous generations as well.

The second chance you get may not be your own. The generations enslaved could only connect to redemption through their dreams; ultimately, those dreams were lived out by their descendants.

Eight months of war has left our community exhausted. There is the war against Israel, conducted by a depraved axis of fanatics and sadists; and then there is the war against the Jews, with antisemites hiding behind masks, both literal and rhetorical.

It is easy to retreat into a type of myopia that sees all of reality from the perspective of the present. The future seems more bitter, because we now have a better imagination for horror and destruction. The glory days of the past mock us, and the promises of dreamers long gone feel like salt poured on fresh wounds.

It is here that we need to remember second chances. We need to search for traces of eternity, and listen for rumors of redemption.

I am not a mystic, but Jewish history has a certain way of surprising rationalists. When looking back at the tragedies and triumphs of the past, there are times when you see second chances played out over decades and centuries. Steven Pressfield, in his book “The Lion’s Gate: On the Front Lines of the Six Day War,” writes the following of June 7, 1967, the day Israeli troops reached the Western Wall:

The first Israeli soldier to reach the Western Wall was Sergeant Dov Gruner.

This Dov Gruner was not the first to bear that name. The original Dov Gruner, after whom ours was named, had been a fighter for the Irgun Zvai Leumi, the underground paramilitary organization that fought the British during the Mandate days, before Israel achieved statehood.

English soldiers captured this first Dov Gruner and put him on trial for participating in an assault on the police station at Ramat Gan. He was sentenced to death by hanging … Gruner refused to defend himself, standing on the principle that to do so would be to acknowledge the legitimacy of the British court.

Dov was hanged at Acre prison on April 16, 1947. As it chanced, his brother’s wife had recently given birth to a son, whom they had named Dov.

This boy grew up to be our Dov.

Moshe Stempel (the deputy commander of that Battalion) was asked once by a journalist, “Why did you pick Dov Gruner to be first to the Wall?”

“I did not pick him,” Stempel replied. “History did.”

Or, if I may put it in other words: History gave Dov Gruner a second chance.

Even when there aren’t second chances, there are second chances.

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz is the Senior Rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in New York.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.