One verse, five voices. Edited by Nina Litvak and Salvador Litvak, the Accidental Talmudist

And a man who inflicts an injury upon his fellow man just as he did, so shall be done to him [namely,] fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth. Just as he inflicted an injury upon a person, so shall it be inflicted upon him.

– Lev. 24:19-20

Gilla Nissan

Teacher. Speaker and Author, “Meditations with the Hebrew Letters”

“An eye for an eye” is a well-known biblical edict, one that is often used by secularists to accuse the God of Israel or His Torah for being harsh and uncompassionate. As always, there is more to this text than well … the eye can see.

At first look, it really doesn’t say who will get even with the one who inflicts injury. It says that there will be an equal counter-loss. That the act will not go unseen. That what sees everything will see this as well. We are being seen all the time; there is a seer in us — a witness who records what we do. There is also a seer on larger scales. God, called by Abraham the “judge of all the land,” is the ultimate Witness and obviously, nothing escapes His eyes. All acts that go against the divine harmonious design, and God’s laws of life given by Moses, need to be paid for, corrected, repaired, healed and returned to their rightful balanced place. On all levels: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual. God’s Creation must be kept fully lawful and respected.

“An eye for an eye”/ayin tachat also means that under or behind (tachat) the eye that you see with is another eye — that mysteriously sees inward. This is also an eye that sees visions — the third eye of the prophets. Judaism is about turning inward, to the Neshama. There, one may find very different information about the injury. More than meets the eye.

Rabbi Gershon Schusterman

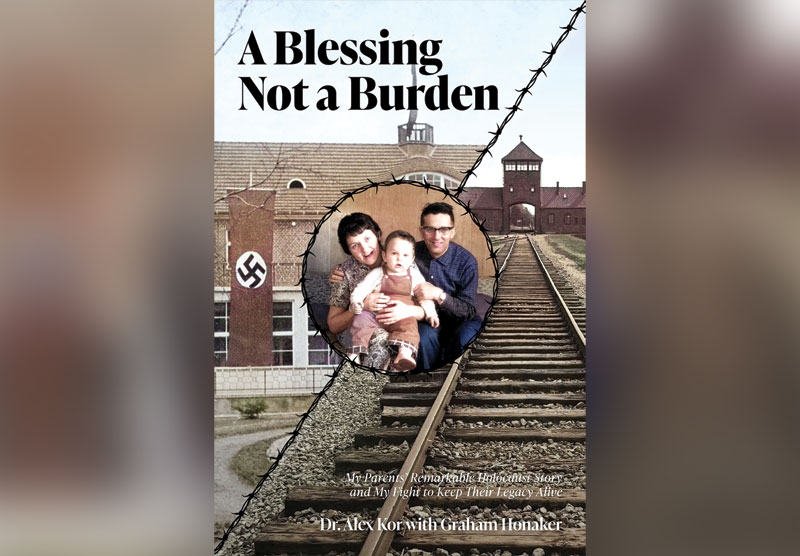

Author “Why, God, Why? How to Believe in Heaven When it Hurts like Hell”

The legal term “Lex Talionis” is the ancient law of “compensation in kind,” that a punishment inflicted on the wrongdoer should correspond in degree and kind to the offense. Understood literally, this leads to the practice in Sharia law that a thief, who stole using his hand, shall have his hand cut off. The Torah’s an eye for an eye might sound similar, but this was never what it was intended for or how it was understood in Judaism. It is meant as monetary compensation.

G-d’s Torah, given to His people at Mt. Sinai 3,336 years ago, has its own methodology by which the text is to be understood. Biblical Hebrew cannot be adequately translated into English. The two differ profoundly. English has far more words than Hebrew. This is why English is a precise language while Hebrew is a pregnant language allowing for many interpretations to the same text, dependent on the rabbinical midwives who birthed the translation and interpretation. Then there is the distinction between the plain meaning of the text, the P’shat, which is entirely different than the literal meaning.

The task of defining what God intended the Torah to mean was entrusted to its recipients, the Jews, using the guidelines given to Moses at Sinai and passed down in the oral tradition, which always was and is an integral part to the wholeness of the Torah.

Ilan Reiner

Architect and Author, “Israel History Maps”

Simply put, the verse can mean that if one breaks the arm of another person, then his arm should be broken as punishment. However, the Talmud argues that the real meaning is that monetary compensation is to be paid when one inflicts an injury on another. Some modern scholars say that the rabbis’ interpretation strays from the original intention of the Torah, which was to inflict a similar injury. The rabbis just couldn’t “stomach” such brutality, so they substituted the physical punishment with a monetary fine.

I’d like to argue that the rabbis’ interpretation is indeed the original intent of the Torah, but not because they couldn’t stomach the brutality. The book of Vayikra is all about Purity (and Impurity), as well as Kedusha (being differentiated) and Completeness. Those are discussed in regards to people, time and the land — specifically the Promised Land of Israel. Anything that’s intentionally not complete, purposely with defects, isn’t desired by Hashem. Such as offerings or treatment of the land (i.e., incomplete Shmita cycle).

We’re all humans. When someone hurts us, our basic instinct is to hurt them back in the same way. Such was the law across the ancient East. However, the Torah tells us that we need to rise above that. Neither we nor the courts should ever inflict an injury on another person on purpose, in order to preserve the sanctity and completeness of our bodies. We shouldn’t damage, mutilate or cause injury to another person, so we can always be desired by Hashem.

Nili Isenberg

Pressman Academy Judaics Faculty

Rabbi Dr. Donniel Hartman and Yossi Klein Halevi invoked our verse in episode 114 of their “For Heaven’s Sake” podcast, reflecting that in this Gaza war the situation “is not an eye for an eye.” When 1,200 Israelis were brutally murdered on Oct. 7 the world saw us, for a moment, as victims. But what happened when our response exceeded (or far exceeded) the loss of 1,200 lives in Gaza? A “proportional response” as explained by the Talmud in Bava Kama is a complicated calculation. In this conflict, many have shockingly characterized our response as genocidal. But the Israeli government has determined that the necessary and proportional response is the elimination of the terrorist organization Hamas, whose members vow to perpetrate massacres like Oct. 7 again and again.

Klein Halevi reflected on the identity of the victims in this conflict, stating that, “the notion that one side or the other is the absolute victim and the other is the absolute victimizer is simply a distortion.” In identifying ourselves as the victims of Oct. 7, we were “lapsing into Jewish powerlessness, which resulted in an abdication of the responsibility of power.” Klein Halevi concluded with a call for Israel to “reclaim the moral responsibilities of power, while affirming the necessity and seriousness of wielding it.”

Having just marked Yom HaZikaron and Yom HaAtzmaut in our calendars, let us continue to strive to establish a just society through our Jewish values, and to find partners who choose reconciliation over conflict and victimhood.

Rabbi Rebecca Schatz

Associate Rabbi, Temple Beth Am

There is no way to read this text and not hear a three-year-old tantrum, or 21st century war. Gandhi famously said “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.” A person who is inflicted by another person should not take out on the attacker the same wrong that the victim received — that is cyclical bullying, or some might say the beginning of ignorant protest.

The Chofetz Chayim wrote in his work Shemirat HaLashon: “If one speaks evil of his friend, things will come to such a pass that they will demean him, too.” People who have done bad things will receive punishment, even if you do not give it to them directly. If we go after every person who hurts us, our reputation is bruised in return for the bruise we might hurt them with.

In today’s world, there is too much that is “sided” and guided by “tooth for a tooth.” We are fighting too often because we need to prove something. We are commenting too much because we need those who we believe are wrong to hear what we think is right. This is 2024 “eye for an eye.” What if we listened to each other rather than cutting their tongues out in an angry tweet? What if we looked onto the other side instead of poking an eye out by reframing their views? What if we lived in a world where we did this because we believed everyone would do this for us too?

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.