When the haggadah asks: “How is this night different from all other nights?” this year’s unprecedented answers are painfully obvious. With everyone on lockdown, the coronavirus defies the Passover tradition of opening your doors to “all who are hungry.”

Instead, the annual festival of unleavened bread offers an opportunity for innovation. Mounting concern for the vulnerable prompted 14 Orthodox Sephardic rabbis in Israel to issue a halachic ruling on March 25 permitting videoconferencing of the seder. The ruling requires launching the technology before sundown Passover eve in accordance with traditional Jewish observance. The decree also comes with an admonition that it applies only to the present emergency.

With what could mean life-threatening exposure for the elderly and those with compromised immune systems, the rabbis wrote in their ruling, “We hope to ensure they have a will to live and fight off disease.”

Closer to home, Sarah Bunin Benor, professor of contemporary Jewish Studies at Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC-JIR), recommends experimenting this year for added spiritual nourishment.

“A virtual seder is a great idea for those who use electronics on the holiday,” said Benor, who founded and directs the school’s Jewish language project, which includes the Jewish language website, which Benor launched in 2002. In January, the Jewish language project became an HUC-JIR initiative, with the mission of promoting the world’s many forms of Jewish communication.

When the hagaddah asks: “How is this night different from all other nights?” this year’s unprecedented answers are painfully obvious.

For Passover, Benor has curated specific materials that you can use at your virtual seder by clicking here.

“It’s important to make everyone feel included by taking turns answering questions, telling stories or doing readings,” Benor said. She also recommended that, if possible, everyone sitting at the same seder operate their own device. And for communal singing, she suggests everyone except the leader turn off their microphones.

Whether you’re hosting a virtual seder or a live event with whomever you are sheltering-in-place, Benor suggests taking time to explore engaging online material in advance. At the seder, Benor said, you’ll then be prepared to “add a new component to liven up the evening.”

The Jewish language website features global traditions with recipes, images and videos, including clips from a recent concert Benor produced. Titled “Passover Around the World: A Multimedia Concert” at the Pico Union Project, the March 15 event originally was intended to be live. Instead, the program — co-sponsored by the USC Casden Institute and supported with an arts and culture grant from the Association for Jewish Studies — was filmed and posted online. Videos from the concert include original arrangements and performances by Jewlia Eisenberg, Jeremiah Lockwood, Chloe Pourmorady and Asher Shasho Levy.

A haggadah supplement offers other ways to implement traditions from around the world, Benor said. During “Dayenu,” for instance, she said, you might borrow the Persian tradition of gently “whipping” each other with scallions.

Or you might be inspired to create a collage or album of depictions of seder night through the ages with contemporary photographs or hand-drawn images of the key dishes at Passover tables from Bukharia, Greece, Libya and Yemen here.

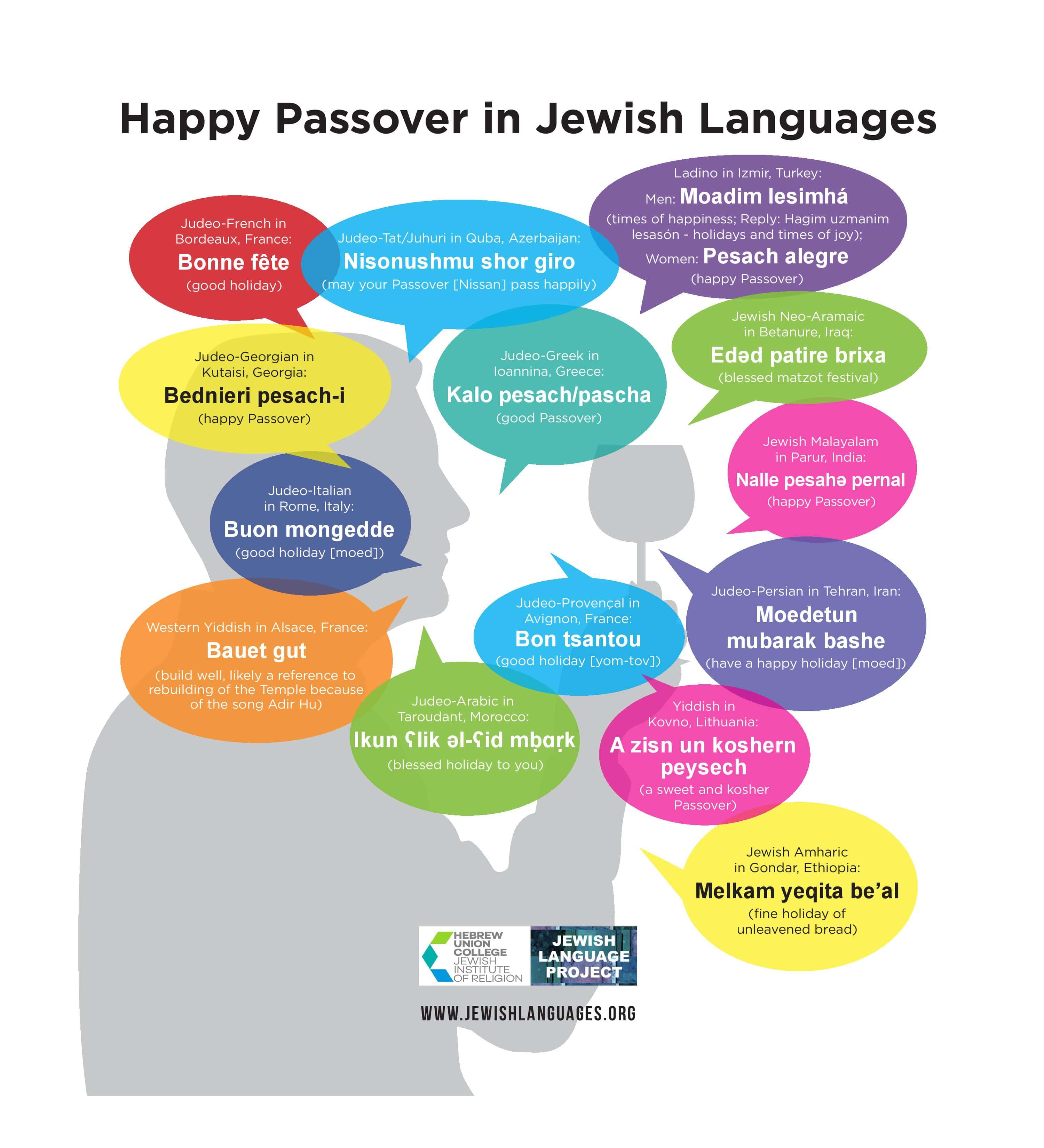

Another option is to introduce a translation of “Who Knows One?” in any of nine languages. Or you could learn “Chad Gadya” in exotic tongues. Texts are available in Judeo-Arabic, Bukharian (Judeo-Tajik), Jewish English, Judeo-Georgian, Judeo-Greek, Judeo-Italian, Ladino, Judeo-Provencal and Yiddish, in addition to the hagaddah’s classic Judeo-Aramaic.

“Most people have heard of Yiddish and Ladino, but hardly anyone knows about Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Tajik and Jewish Malayalam, to give just a few examples,” Benor said. “A few years ago, I started building a broader initiative to raise awareness about Jewish languages.”

Enhancing a seder with language is a natural extension of the project, she said. “You can share fun facts like the different words for matzo and charoset in various Jewish languages.”

Or, she suggested, you might share other factoids. Jews in Arabic-speaking lands, for instance, traditionally avoid eating chickpeas on Passover, even though they eat other kitniyot. One reason? The word for chickpeas — hummus — sounds too similar to the word for leavening, chametz, in Judeo-Arabic, Benor said.

The site also offers Passover greetings with examples in Yiddish—A zise un koshern peysech, Ladino — Pesach alegre and Jewish Amharic — Melkam yeqita be’al.

May it be so.

Lisa Klug is a freelance journalist and the author of “Cool Jew” and “Hot Mamalah: The Ultimate Guide for Every Woman of the Tribe.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.