The three lions of contemporary Israeli literature, Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua and David Grossman, held a press conference a little over four years ago, pleading with then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert to end the bloody incursion into Lebanon.

A few days later, the Israeli government agreed to a cease-fire, just after an army “notifier” visited the Grossman family with the announcement that their youngest son, Uri, had been killed in action.

The interaction between private concerns and public events is a major part of David Grossman’s worldview and of his latest novel, “To the End of the Land” (Knopf: $25).

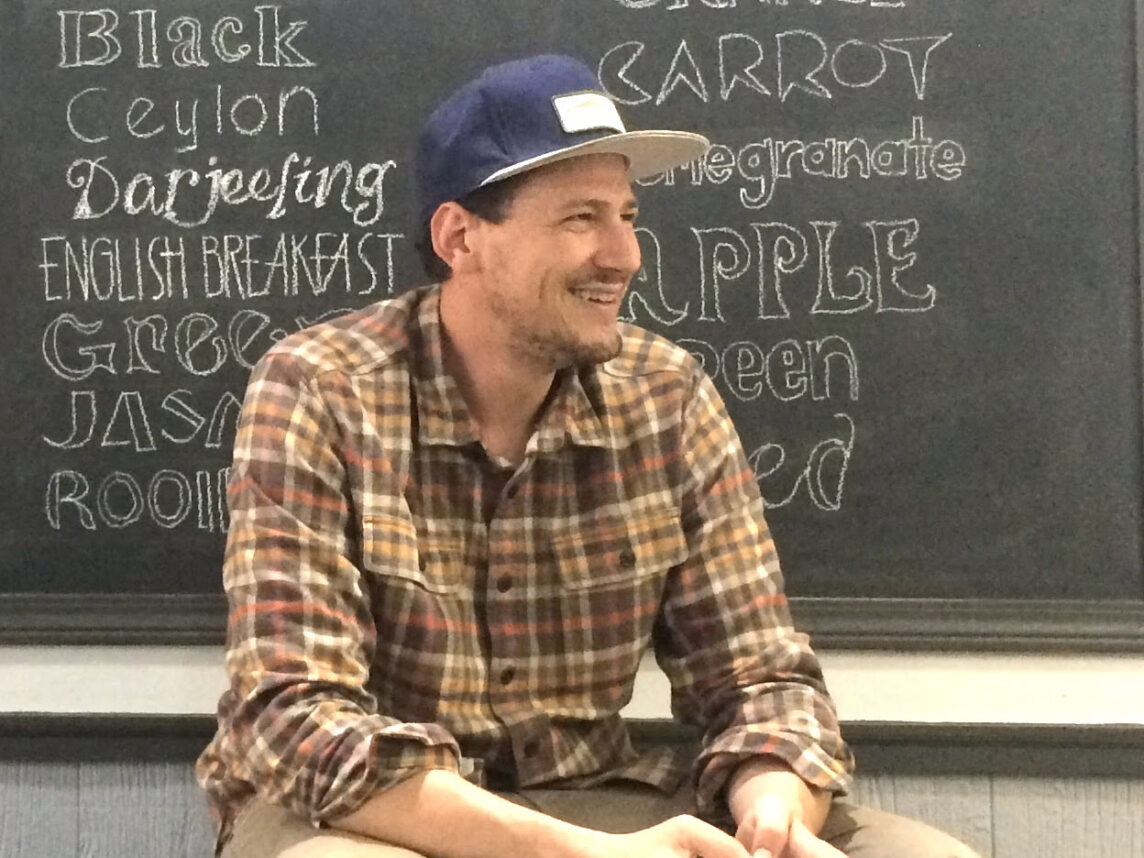

On Oct. 19, Grossman stood on the central bimah of Stephen S. Wise Temple and talked to some 300 listeners, who had braved a dark and stormy night, about his private life as a writer and his public life as a peace activist.

Although the thin, sandy-haired Grossman said he wanted to talk about his writing, not Middle East politics, it proved impossible to separate the two.

He started writing “To the End of the Land” three years before his son’s death, and the book was almost finished when the news came, but the book’s plot and tone speak of an eerie prescience.

The book’s Hebrew title, “Isha Borahat MiBesora” (“The Woman Who Runs From the Notifier”), almost summarizes the book’s major theme.

Reading from the book in Hebrew and English, Grossman introduced Ora, whose son Ofer is about to be discharged after fighting in Lebanon, only to volunteer for a new campaign on the West Bank.

Constantly in fear of the notifier arriving to announce her son’s death, Ora hits on the stratagem of running away for long hikes through the land, without a cell phone or notification to anyone. That way, she feels, the notifier won’t be able to find her to deliver his message, as she weaves a symbolic protective cloth over her son.

In her long walks, accompanied by her former lover, she talks about her life, her family and the state of her country.

Of course, this summary can’t do justice to the massive book, which has received high critical praise in Israel, the United States and lands in between, but it serves as an entry point to Grossman’s observations and answers on diverse topics.

Why did he did he choose a woman as the central protagonist of his novel?

“War is created by men. A woman always retains a remnant of the fetus in her womb. … If God had asked Sarah to sacrifice her son Isaac, she would have told God, ‘Give me a break,’ and refused His order.”

On human solitude: “Every couple makes a deal that they will view each other in a certain way. … We love our children, but there are still dark corners we are afraid to explore, we don’t want to know about our brother’s nightmares. … Even during sex, we do not know each other’s heart.

“But a writer totally invades another person’s life. …When I write, I hide a family of hundreds underground, and I am the only one who knows where they are.”

On grief and writing: “The first week after a family member’s death, you’re exiled from everything, but the day after the end of shiva, I went back to the book. I asked myself at the time, ‘My world has been destroyed, why should I bother finding the right word?’

“But then I found that giving my characters shape and body brought me back to life. This is a book about life, not war.”

On the media: “The mass media is the greatest superpower that pollutes our lives and turns people into mobs. … The mass media prevents us from seeing reality and what is being done in your name.”

Writing tips: “I revise my writing constantly. For ‘To the End of the Land,’ I wrote 12 versions. One morning I came down to breakfast and my wife said, ‘You look happy today,’ and I said,‘Yes, I finished a version of my book last night.’ So she said, ‘Yes, and tomorrow you’ll start on another version.’

“I always read aloud anything I have written. When I can hear my own voice, I know what the reader will hear.”

On book translations: “A book loses something in translation, but it also gains something. It’s like looking at twins — they are not exactly alike, but by looking at one you can learn something about his brother.”

On American politics: “During my speaking tour of the United States, I hear everywhere that America is in decline. … I still have great faith in President Obama. … An American president must pay attention also to the needs of Palestinians.”

On Israel: “We are still not confident about our own existence. Other governments can make plans for the distant future, but we won’t make plans for even 20 years ahead. …We are born with the fear that we may have to bury our own children.”

On Palestinians, Israelis and peace: “Israel and the Palestinians mirror each others’ distortions. … We have hateful fundamentalists on both sides.”

“I want to see how Palestinians go about building up a nation. Everyone is entitled to dignity, but they must not endanger Israel.”

“Without clearly defined borders, we are like a man who lives in a mobile home, whose walls keep expanding and contracting.”

“Only through peace will we realize the chance to live in our own homeland. Peace is more important than ruling over this or that piece of land.”

Grossman’s talk was the opening event in a series of lectures and dialogues presented by the temple’s Center for Jewish Life. Future speakers will include Rabbis Marvin Hier, Shmuley Boteach and David Woznica, historian Deborah Lipstadt and Yale clinical professor of surgery Sherwin Nuland.

For information, phone (888) 380-9473 or check www.WiseLA.org/CJL.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.