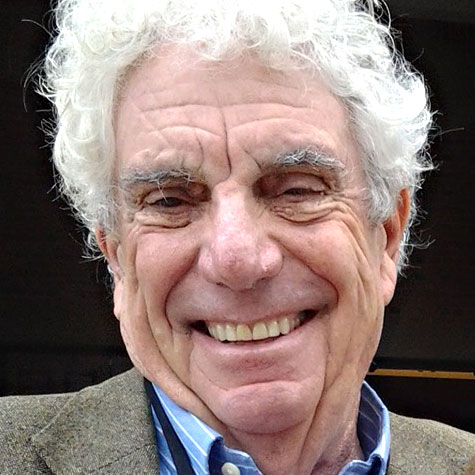

A visit with Dr. Eugene Gettelman, who celebrates his 100th birthday on June 17, shows how much medicine has gained and lost in the last half century.

We talked recently in the sitting room of his apartment at Westwood Horizons, an upscale retirement home near UCLA. His friend, Dr. Herb Levin, had suggested I do a column on Gettelman’s reaching the century mark.

I had met them when I was invited to speak at a monthly luncheon of retired physicians at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Occasionally, Gettelman, Levin and their friend, Dr. Fred Kahn, take me to lunch at the UCLA Faculty Center. They like to talk about politics. I’m interested in the old days of medical practice — at least their old days.

That’s what I wanted to talk about when Gettelman and I settled down for a chat. As a pediatrician practicing in the San Fernando Valley, he treated generations of children, starting from when he completed Navy service in the South Pacific during World War II. He is a lively man with a friendly and calm manner, undoubtedly reassuring to parents and children as well.

I asked him to repeat a story he had told me before, which I thought illustrated the sharp instincts, intelligence and guts that were so necessary to doctors working without today’s sophisticated diagnostic tools and drugs.

Gettelman was senior resident at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago in the mid-1930s. In those days — hardly imaginable today — strep throat was a dread ailment that could affect the mastoid and turn into meningitis. For the children he was treating, “it was like a death certificate,” he said.

At the time, 100 Jewish physicians who had fled Hitler’s Germany were working at Reese, a Jewish hospital. One of them came to Gettelman with a German article telling how doctors there were using sulfa drugs to cure infections, a new treatment first tried in 1932.

Several children were dying in Reese Hospital from meningitis. “I had more guts than brains in those days,” Gettelman said. He called the manufacturer, Bayer, in Germany. The company air expressed a pound of a powdered version of the drug.

There were no directions with the package. The drug, Gettelman said, had never been used against meningitis. But he decided to try it.

He asked the parents. He told them their children were dying. The parents told him to go ahead. Gettelman mixed the powder with a solution in what he thought would be a safe proportion and injected it into the spine of one of the sick children.

“It worked,” Gettelman said. “With the first patient, the temperature came down.”

The story reminded me of House, television’s irascible high-risk doctor, who operates on instinct, experience and guts.

“Do you watch ‘House?'” I asked Gettelman.

“Sometimes,” he replied.

“House would have done what you did,” I said.

Gettelman smiled. “That’s exactly right,” he said.

In Gettelman’s younger days, doctors marched through the hospital in something called “grand rounds.” Held on Sunday mornings, when all the doctors were available, the rounds were led by the head of the department, dressed in morning coat and striped pants, followed by a procession of residents and interns from one hospital room to another.

They descended on patients, who must have been surprised, if not scared. The lowest-ranked intern would spell out the symptoms. The head doctor would question the usually nervous intern. Then the group would retreat to the hall, and the department chief would explain the lessons to be drawn from the case.

When he was practicing in the Valley, Gettelman visited patients at Encino Hospital in the morning, saw ill children in his office all afternoon and made house calls in the evening. Doctors knew their patients and watched for symptoms. They didn’t dismiss childhood headaches, Gettelman said. A headache could mean polio. “A belly ache could be appendicitis,” he said.

Those days are gone, he said, and with them the young doctors who opened solo offices and started treating patients one on one, becoming part of their lives. Today’s doctors’ offices are big. Some are well organized, others not.

“The personal relationship between the doctor and the patient has deteriorated,” he said.

But on the plus side, antibiotics have all but eliminated the crises Gettelman faced in his youth. These days, he wouldn’t have to play a hunch and order those sulfa drugs from Germany.

He noted approvingly that radiology has made possible huge advances in diagnosis. Gettelman keeps up on medical developments, and he attends frequent lectures and other sessions at Cedars and UCLA.

On Sunday, June 15, family and friends will gather at the UCLA Faculty Center to celebrate his birthday. Gettelman and his late wife, Rita, had two sons, Alan and Michael. There are five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

My interview was ending. We had talked for an hour, and it was lunch time. Gettelman walked to his closet and pondered which of his several sport coats to wear downstairs for lunch. He chose the camel hair.

A table had been reserved for him. He ordered the salad, and I had the turkey sandwich. We discussed politics, not agreeing all the time, but enjoying the conversation. After an hour, the dining room was emptying, and I stood up to leave.

As I drove home, I thought about all the changes Gettelman has seen and what a remarkable man he is. This was one visit to the doctor that actually made me feel good.

Until leaving the Los Angeles Times in 2001, Bill Boyarsky worked as a political correspondent, a Metro columnist for nine years and as city editor for three years. You can reach him at bw.boyarsky@verizon.net.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.