Jews are used to stories that start and then begin again. Two versions of creation launch the Torah. Two tellings of our history commence (and re-frame) the Passover Seder. The Haggadah starts telling our tale by offering, “in the beginning, our ancestors worshiped idols” and then begins again with, “our ancestor was a wandering Aramean.” Sometimes, there are just too many insights to cram into a single version. Some stories resonate in ways that make them worth multiple tellings.

Some stories resonate in ways that make them worth multiple tellings.

Turns out that Thanksgiving is one of those tales. There’s just too much to unpack in a single version. So, I propose here to tell it twice. And then twice again.

Thanksgiving #1: Puritans and Natives

The version of Thanksgiving that many of us grew up hearing was of a band of hardy Puritans who landed on Plymouth Rock in 1620 and survived their first grueling year because of the wisdom and care of the local First People. After the locals taught the Pilgrims to build and hunt and how to plant the local produce, the English immigrants celebrated their survival with a visiting delegation of Natives at a festive meal that featured local delicacies (turkey, gourds, potatoes, green beans, cranberries, corn and, of course, pumpkin pie). This Thanksgiving story focused on the Pilgrims, offering a religious (Christian) context for this celebration: arrival in a new land, divine favor for the mission of the new arrivals, religious freedom for monotheists.

The first retelling of the story broadens our focus to tell the story of the Pilgrims, certainly, but it also recognizes the Natives as Native Americans. Their story is no longer a supporting role to the (European, Christian) stars. Their story is now our story, too.

So, let’s offer a more expansive retelling.

When the Europeans first came to what we now know as New England, they found a continent full of people. Estimates suggest that 50 to 100 million people were living on the continent at the time. The northern coast of the Atlantic, for example, was packed with people, villages and farms. And the locals didn’t really want permanent European neighbors. When the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, came to the area several years in advance of the English, the locals were willing to trade with his group, but they then sent them on their way.

Although Champlain and his ships left, they had to leave behind a handful of Frenchmen who were prisoners (or slaves) of the Native Americans. The Frenchmen told their captors that their God would decimate them for their rejection of the Europeans. The Native Americans were skeptical that the European God could be so powerful.

When the English Pilgrims arrived a decade later, they encountered a drastically different landscape. The French had introduced new diseases for which the Native Americans had no immunity, wiping out a majority of the population. When the English arrived, they found empty villages and fields prepared for farming but with no farmers. The surviving Native Americans were terrified of the consequences of these Europeans and their God. Both Native Americans and Pilgrims accepted a religious conquest explanation for why there was no Native American opposition and why the Pilgrims would triumph. This narrative may explain why there was no opposition to the establishment of the Plymouth Rock settlement: a shared sense of inevitable destiny.

That first Thanksgiving dinner is a recognition that the Europeans were here to stay. The American story would now forever include them and their progeny. It was indeed a triumph for the fragile new community. But our telling of the story is no longer just about the Pilgrims. We can also integrate the tale of the Native Americans and their culture as vital to the larger story. The English pilgrims did benefit from native wisdom and experience freely shared. In that sense, they and their descendants are also heirs to the rich heritage of Native American culture, faith and resilience. But our telling must also include the tragic and unanticipated consequence of biological intrusion: the widespread deaths that devastated the Native American population and launched an ideology of Manifest Destiny, the belief in the inherent superiority of European settlers, European culture, and any conquest they could sustain.

That Thanksgiving dinner was a pause before the storm and a beacon of possibility that we have yet to fully implement: an expansive identity as Americans that not only treasures our roots in religious dissent and yearning for freedom but also honors Native wisdom, community and generosity. Our tale can mourn the victims of these powerful ideas and civilizations and the complex realities they generated.

Thanksgiving #2: Power and Slavery

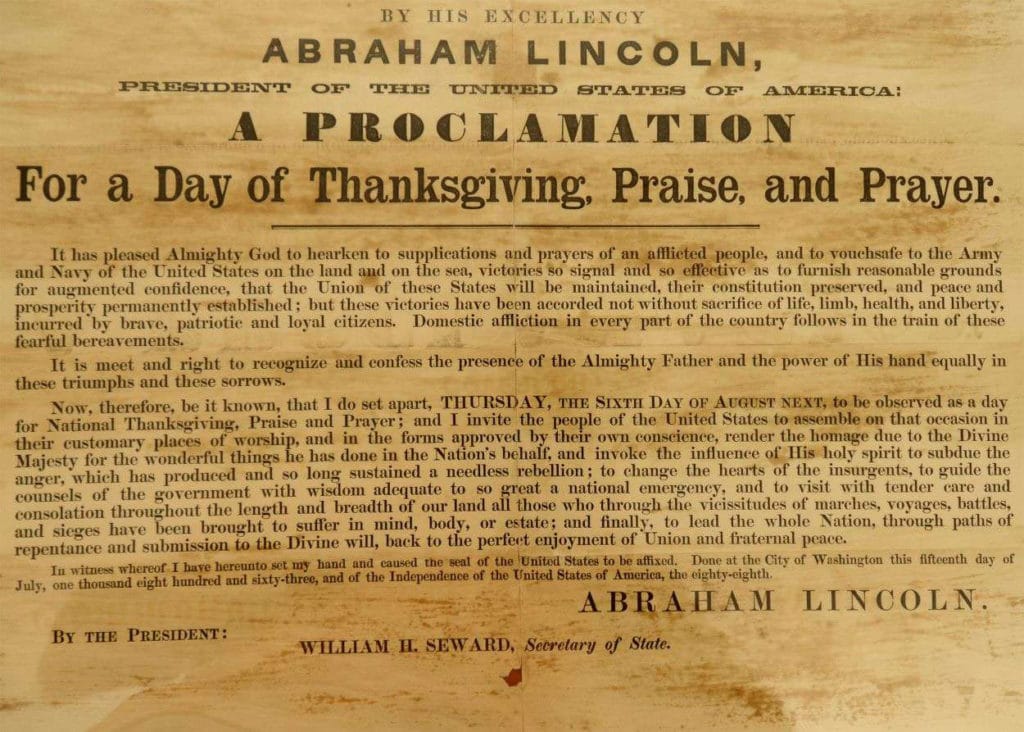

The Thanksgiving story I grew up with also involved a second tale. That second story centered around our sixteenth president, Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator. As I was taught, in the midst of a righteous war to end the scourge of slavery, President Lincoln issued a call to the nation to express “Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.” In an 1863 proclamation, the Lincoln administration called upon the citizens of the United States to offer prayers “with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife … and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation, and to restore it … to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility, and Union.” In my family’s telling of this tale, we affirmed the United States’ fundamental decency as a country united in opposition to slavery and proclaimed the dinner as the paradigmatic American celebration of liberty, justice and freedom for all.

But, of course, this second story is more complicated, too. It is true that President Lincoln is justly remembered as the emancipator of the slaves. But history reveals that ending slavery was not his original motivation (re-read the quotation above, and you will discover no mention of slavery at all). Lincoln famously and repeatedly observed that if he could save the Union and not end slavery, he would have been willing to follow that path. His primary motivation when the Civil War launched was to preserve the Union of the United States. But as the war developed, it became clear to him, General Grant and many others that the issue of slavery was so deep and fundamental to any future unity as a nation that it required clear and unambiguous opposition. Upon issuing the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, Lincoln finally sided with the Abolitionists and changed the course of the war and the ideal of American liberty that we still struggle to attain. The Civil War began as a power struggle, but it grew into an instance of moral advance.

A more nuanced telling of this Thanksgiving story requires us to retell the story of America not only as the dictate of white Protestants but also from the perspective of the marginalized and the suppressed. How slaves created meaning and dignity in a bloody and brutal system and how women and others were able to begin the work of claiming their voices and their place in public — these groups are now vital aspects of our Thanksgiving story. Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, John Brown and others, are now part of the pantheon of heroic Americans we center, emulate, and celebrate. We dare not omit their perspectives and insights.

Giving Thanks and Moving Forward

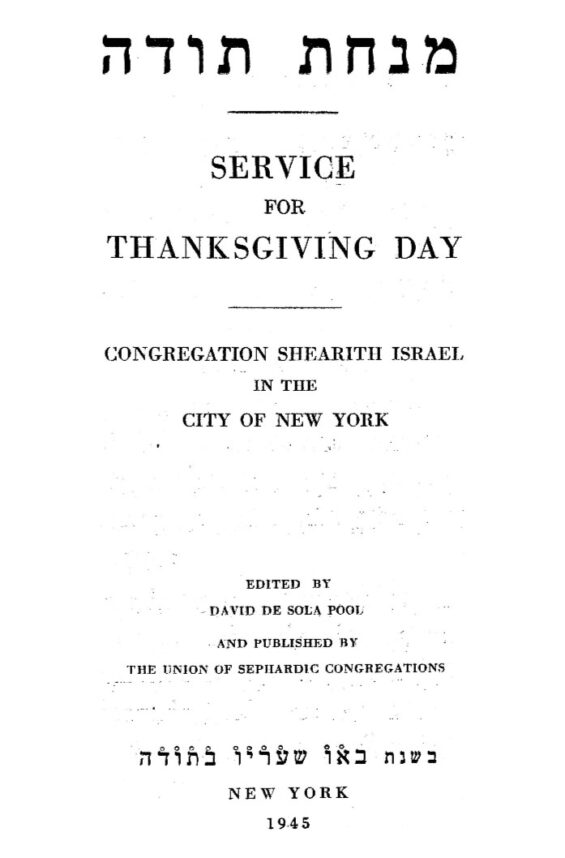

The Talmud asks which of the Temple sacrifices will no longer be needed in the Messianic future and which will continue. Not surprisingly, the Sages of old affirmed that there will always be a place for the Thanksgiving (Todah) Offering. Gratitude is an abiding affirmation of what is best in human character and gratitude remains a pressing psychological need to inspire us to be self-surpassing. In offering thanks, we place ourselves in a future of hope and aspiration rather than allowing ourselves to be trapped in a past of determinism and despair.

As we gather this Thanksgiving — in cyberspace and in pods — we continue to heed the mandate to reorient ourselves with the healing affirmation of gratitude. We thank as a spiritual exercise of resilience and of possibility. As the Siddur reminds us three times each day: “We thank you, Lord our God and God of our ancestors, throughout all time. You are the Rock of our lives, the Shield of our salvation in every generation. We thank you and praise you morning, noon and night for Your miracles which daily attend us and for Your wondrous kindnesses.” More than God may need our thanks, we need to become people of gratitude.

But for our Thanksgiving to do its redemptive work, we must tell the stories that are truly worthy of real gratitude: stories in which we can all see ourselves and hear our voices in all their divergences and disparities, stories too nuanced and complex to be told only once. Rather than flattening our shimmering sparkles into uniformity, can we tell multiple versions of our founding stories so that the raucous symphony of sounds creates something grander than any of its single component tunes? By including more stories previously ignored or overlooked, we make the telling of them that much more of an inspiration. And we illumine the path for a tomorrow of promise for us all.

There is always more to be thankful for.

Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson, a contributing writer, is the Abner & Roslyn Dean’s Chair of the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies at American Jewish University, where he is Vice President. Thanksgiving remains one of his favorite holidays.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.