Editor’s note: This opinion tackling the United Nations Human Rights Council is the “pro” argument published in conjunction with the “con” argument written by Roz Rothstein and Max Samarov, “When will the UN Human Rights Council follow its own mission?”

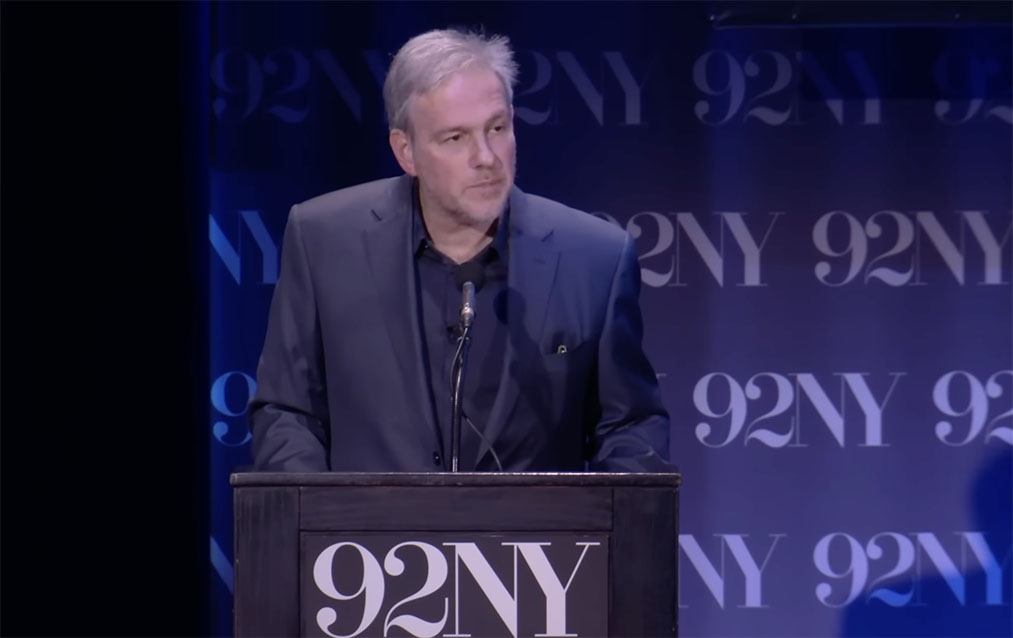

Nearly three years ago, the United Nations Human Rights Council appointed me as its monitor — “special rapporteur” — on freedom of expression. I report to the council about the worst abuses of expression worldwide, such as attacks on journalists and independent media, members of vulnerable minorities, and the ability of anyone to seek, receive and impart information online. In this position, I know the council, its strengths and its weaknesses.

Composed of government representatives, the council gathers for several weeks every March, June and September in an ornate conference room at the Palais des Nations, the European headquarters of the United Nations in Geneva, to proclaim a commitment to such fundamental human rights as the prohibition of torture, extrajudicial killing and arbitrary detention, as well as the rights to freedom of expression, religious belief and peaceful protest.

From my experience, I can say one thing with certainty: Activists around the world, in every country, value the council as a central global platform for their voices to be heard. In my missions to Turkey, Tajikistan and Japan last year, journalists, lawyers, judges, teachers, humanitarian workers and activists all sought the help of the U.N. — at the very least, its moral support. While a U.N. visit or statement may get lost in the Western media, in many countries around the world, a word from a U.N. official or the Council can instigate controversy for days, sometimes even leading to solutions.

To be sure, the council is not a human rights nirvana. Its flaws are well-known. Forty-seven governments — including the United States — are elected to sit on the council and all other governments have a seat in the room at the Palais. Many violate human rights norms regularly, some in repressive and violent ways. These flaws, according to our new Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, seem to be moving the Trump administration to consider whether the United States should abandon the council seat it won last year.

I believe the case for leaving the council is extraordinarily weak. If the administration, like Barack Obama’s administration before it, strongly objects to the council’s “biased agenda item against Israel,” as Tillerson put it, then the place to fight that bias is from within. Few listen to those outside, and few outside have the tools or the leverage to make reform.

Others have made the case for why the council serves American interests. As Suzanne Nossel, a former State Department official and current head of PEN America, has summarized it in a must-read contribution to the debate, U.S. departure from the council would help cede control of the human rights agenda to authoritarians — exactly those that the council is supposed to resist and restrain. She notes that a council with the United States has historically been better for human rights globally, not to mention better for Israel.

These realpolitik arguments work. Leaving the council makes no sense if we are talking about U.S. national interests.

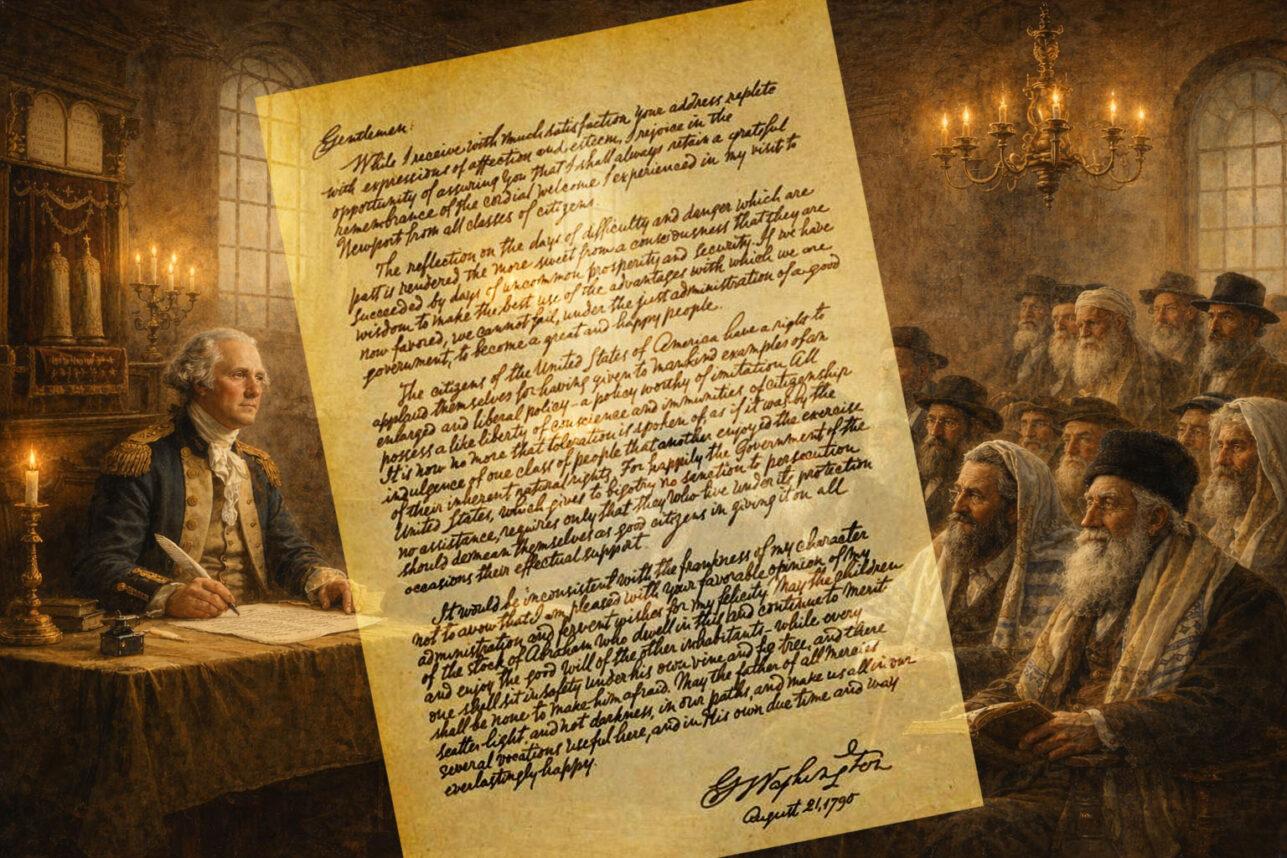

For me, as someone who heard of tikkun olam before human rights, the council has merit on its own. We constantly sought venues for our own demands for the rights of Soviet Jews during the years of the Cold War or for the rights of African-Americans during the civil rights era. In recognizing that kind of searching today, the council amplifies the messages of those deprived of a voice or denounced as enemies of their people in their home countries.

Consider the kind of discussion that can take place during council meetings. In an era when governments kill their opponents, jail their chroniclers and repress their critics, human rights talk may seem wildly out of sync with the times. Yet there at the Palais, one by one, individual human rights advocates rise from their seats in the back of the room and make their way to microphones so that every person there — every government representative, every U.N. official — can hear. They have come from all corners of the world, and they say what the governments need to hear, calling them out for their abuses in front of a global audience.

You might hear, as I have, Bahraini advocates identify friends and family members held in prison merely for criticizing the government, some for doing so on Facebook or Twitter. You might hear criticism of Saudi Arabia for its jailing and flogging of bloggers, or condemnation of Turkey’s massive attack on the media, the bureaucracy and opposition politicians. You might learn of the ways in which Iran silences and represses its Baha’i minority, in areas such as education, music and religious tradition.

You might hear from a refugee who has fled totalitarian North Korea or war-ravaged South Sudan, a member of the Muslim Rohingya community subject to attack and statelessness in Myanmar, or from a Tibetan activist recounting the repression of Chinese authorities. You could be brought to outrage from stories of hunger in Venezuela, driven by authoritarian governance, or of fear from stories of LGBT communities in Cuba, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Uganda and elsewhere.

This is more than idle talk; these individual interventions can have impact. The voices of victims and advocates have helped lead to important outcomes: special commissions to tell the truth about human rights abuses in North Korea or the brutality of ISIS and the Bashar Assad regime in Syria or special monitors to report on the human rights crises in Iran, Cambodia, Myanmar, South Sudan and many other places — including, yes, the West Bank and Gaza. In some cases, stories told in Geneva have helped lead to sanctions adopted by the U.N. Security Council in New York.

In response to advocacy by nongovernmental organizations, the council also has created special mandates and appointed individual experts to monitor human rights issues worldwide, including freedom of religious belief, peaceful protest, violence against women, racism and housing (and the one I hold on freedom of expression). It has condemned all manner of human rights abuses, from anti-Semitism to discrimination against women, from racist crimes to attacks on workers’ rights. Through its Universal Periodic Review, the council reports on every country’s human rights behavior, allowing local and international activists a role in that process.

Leaving the council makes little sense if we still are to maintain that human rights play some significant role in America’s engagement in the world, even if not a leading or pivotal one. The U.N. isn’t perfect, and neither is the United States. But walking away from human rights is not who we are, and it’s not where we should go.

Reform the council, yes. Criticize its biases, sure. But recommit to it. Fix it. And make it work for those who need it worldwide.

David Kaye is a law professor at UC Irvine School of Law and the U.N. special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression. He can be found at @davidakaye and freedex.org.