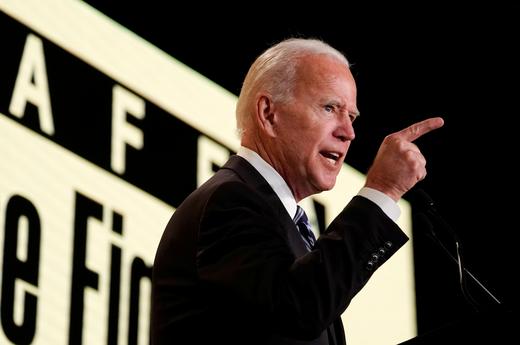

Former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden addresses the International Association of Fire Fighters in Washington, U.S., March 12, 2019. Photo by KEVIN LAMARQUE/ Reuters

Former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden addresses the International Association of Fire Fighters in Washington, U.S., March 12, 2019. Photo by KEVIN LAMARQUE/ Reuters Most presidential campaigns are about the economy, or matters of war and peace. Can Joe Biden make the 2020 election a referendum on white supremacy? If he can, he will win. If not, President Donald Trump’s chances for re-election get a lot better.

While most of the other Democratic candidates are debating how aggressive they should be pushing to reverse Trump’s agenda on a number of fronts, Biden is taking a decidedly different approach. He is arguing not against Trump the policymaker, but against Trump the person. While Biden has indicated the outlines of his platform and has promised more details going forward, it’s clear that he will frame his campaign primarily as a moral indictment against the incumbent.

The safer and more conventional approach, which all of the other 20-plus Democratic candidates are taking, is to try to beat Trump on the issues. That’s how Nancy Pelosi’s forces took back the House last year, by talking about health care and other policy matters rather than taking Trump’s bait.

On the presidential campaign trail, this has played out as an internal Democratic debate over different degrees of progressivism. Should universal health coverage be achieved through a Bernie Sanders-preferred single-payer system or through less sweeping means? Should the nation institute something along the lines of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal or fight climate change in a more measured Barack Obama-era way? Similar shades-of-blue distinctions are being drawn on criminal justice, taxes, education, housing, immigration and foreign policy.

Biden is arguing not against Trump the policymaker, but against Trump the person.

But Biden is gambling that while the voters who will decide a general election may disagree with Trump on many policy matters, they are much more uncomfortable with the president’s personal conduct. That’s why the most significant aspect of Biden’s launch has been his repeated references to the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., and to Trump’s comment about “fine people on both sides” of the events there. Biden clearly believes that this was a defining moment in Trump’s presidency and in recent American history, and he clearly intends to make it the centerpiece of his campaign. The president’s recent efforts to reframe those remarks in a less objectionable context suggest that he knows the harm that a sustained debate about Charlottesville could cause his chances for re-election.

The conventional wisdom that developed after the 2016 campaign is that Trump’s opponents place themselves at a great disadvantage when they engage in his type of personal combat. So for the last two-plus years, the president’s foes have instead trained their fire on his least popular policy goals.

Until Biden. The unique calculation he has made is that the way to beat Trump isn’t to abandon the strategy that Clinton employed in 2016, but rather to just do it better. Biden’s advisers believe that the former vice president’s “Middle Class Joe” relatability will allow him to connect with the white working-class voters in a way that Clinton simply could not.

Biden’s first challenge is to make it out of a Democratic primary populated with alternatives that are a more natural generational and ideological fit for the new Democratic Party. His struggles to address the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearings in the first days of his campaign portend ongoing difficulty on this front, as does his habit of praising Republicans with whom he has worked.

If he becomes the nominee, he must then confront Trump’s ability to marshal populist animosity toward the traditional political system. Biden might be more likable than Clinton, but he has been in Washington even longer, which makes him a ready-made target for Trump’s attacks against the establishment.

Biden’s final challenge with this approach is one of consistency. As those of us in the Jewish community know, hatred and prejudice come from both the far right and the far left. Just as ugly strains of nationalism can ooze into anti-Semitism and other racial and ethnic bigotry, the most virulent strains of anti-Zionism in some progressive circles can turn into equally repulsive forms of anti-Semitism.

Can a character-based message take Biden to the White House? Perhaps, but only if it’s applied evenly.

Dan Schnur is a professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies and Pepperdine University.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.