Neocon icon Norman Podhoretz has a new book questioning the tradition of Jewish liberalism and, more aptly, the current relationship between Jews and liberal causes. “Why Are Jews Liberal?”—to which the Tapped blog from The American Prospect responds: “Why is the sky blue?”

True, true. I still remember when I first learned that Republican Jew wasn’t the punchline to a Borscht Belt joke.

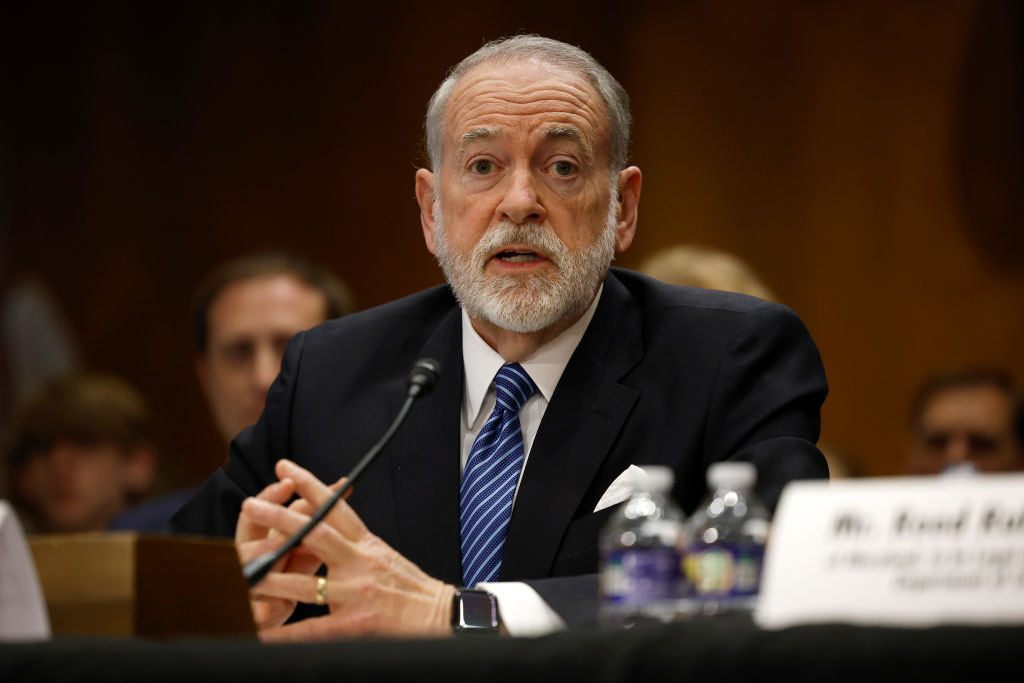

Podhoretz’s book has been making the rounds, and he had a related op-ed in Thursday’s Wall Street Journal. Podhoretz wrote:

Most American Jews sincerely believe that their liberalism, together with their commitment to the Democratic Party as its main political vehicle, stems from the teachings of Judaism and reflects the heritage of “Jewish values.” But if this theory were valid, the Orthodox would be the most liberal sector of the Jewish community. After all, it is they who are most familiar with the Jewish religious tradition and who shape their lives around its commandments.

Yet the Orthodox enclaves are the only Jewish neighborhoods where Republican candidates get any votes to speak of. Even more telling is that on every single cultural issue, the Orthodox oppose the politically correct liberal positions taken by most other American Jews precisely because these positions conflict with Jewish law. To cite just a few examples: Jewish law permits abortion only to protect the life of the mother; it forbids sex between men; and it prohibits suicide (except when the only alternatives are forced conversion or incest).

The upshot is that in virtually every instance of a clash between Jewish law and contemporary liberalism, it is the liberal creed that prevails for most American Jews. Which is to say that for them, liberalism has become more than a political outlook. It has for all practical purposes superseded Judaism and become a religion in its own right. And to the dogmas and commandments of this religion they give the kind of steadfast devotion their forefathers gave to the religion of the Hebrew Bible. For many, moving to the right is invested with much the same horror their forefathers felt about conversion to Christianity.

All this applies most fully to Jews who are Jewish only in an ethnic sense. Indeed, many such secular Jews, when asked how they would define “a good Jew,” reply that it is equivalent to being a good liberal.

I’ve got to agree with this analysis, but, of course, there is a difference between Jewish tradition and Judaism.

Not surprisingly, Leon Wieseltier, the literary editor of The New Republic, isn’t a fan. He reviewed “Why Are Jews Liberal?” for yesterday’s New York Times and pulled no punches:

Norman Podhoretz loves his people and loves his country, and I salute him for it, since I love the same people and the same country. But this is a dreary book. Its author has a completely axiomatic mind that is quite content to maintain itself in a permanent condition of apocalyptic excitation. His perspective is so settled, so confirmed, that it is a wonder he is not too bored to write. The veracity of everything he believes is so overwhelmingly obvious to him that he no longer troubles to argue for it. Instead there is only bewilderment that others do not see it, too. “Why Are Jews Liberals?” is a document of his bewilderment; and there is a Henry Higgins-like poignancy to his discovery that his brethren are not more like himself. But the refusal of others to assent to his beliefs is portrayed by Podhoretz not as a principled disagreement that is worthy of respect, but as a human failing. Jews are liberals, he concludes, as a consequence of “willful blindness and denial.” He has a philosophy. They have a psychology.

“Why Are Jews Liberals?” is a potted history followed by a re-potted memoir. The first half of the book, which tells the story of “how the Jews became liberals,” is narrated in “the impersonal voice of a historian — an amateur, to be sure, but one who has relied on a variety of professional authorities for help and guidance.” These chapters are mainly anthologies of congenial quotations. There is something a little risible about the solemnity with which Podhoretz presents encyclopedia articles as evidence of his erudition (“I relied most heavily on one of the great works of 20th-century Jewish scholarship, the Encyclopaedia Judaica”); there is even a reference, slightly embarrassed, to Wikipedia. From his footnotes you would think that the most significant Jewish historian of our time is Paul Johnson. And there is a decidedly insular reliance upon the pages of Commentary, the magazine he edited for 35 years. His parochialism can be startling: Samuel ha-Nagid, the astounding poet, warrior, statesman and scholar in Granada in the 11th century, reminds him of Henry Kissinger! Podhoretz seems to be living the Vilna Gaon’s adage — maybe he can find it in some encyclopedia — that the best way for a man to preserve his purity is never to leave his house.

Like I said. You can read the rest of that review here.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.