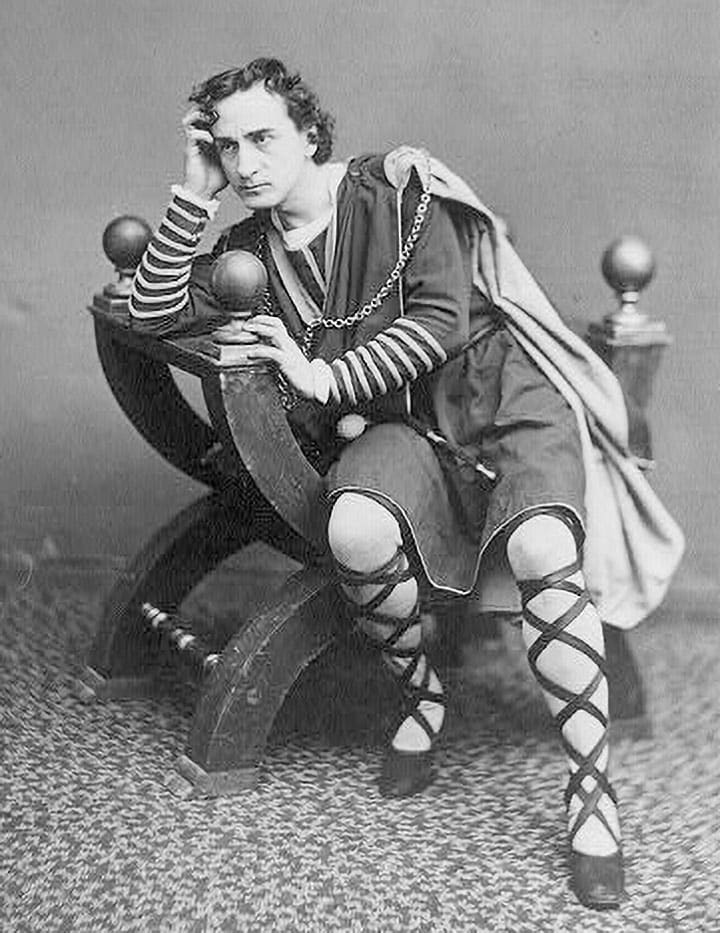

The reason Hamlet never had much peace

is that he asked, “To be or not to be,”

translated into Hebrew “live or cease,”

lihyot o laḥdol, made by meḥdal as unfree

of peace of mind as not just Israelis

but Jews throughout the universe became,

doomed like him by meḥdal to fail, ease-

deprived, attributing to themselves the blame,

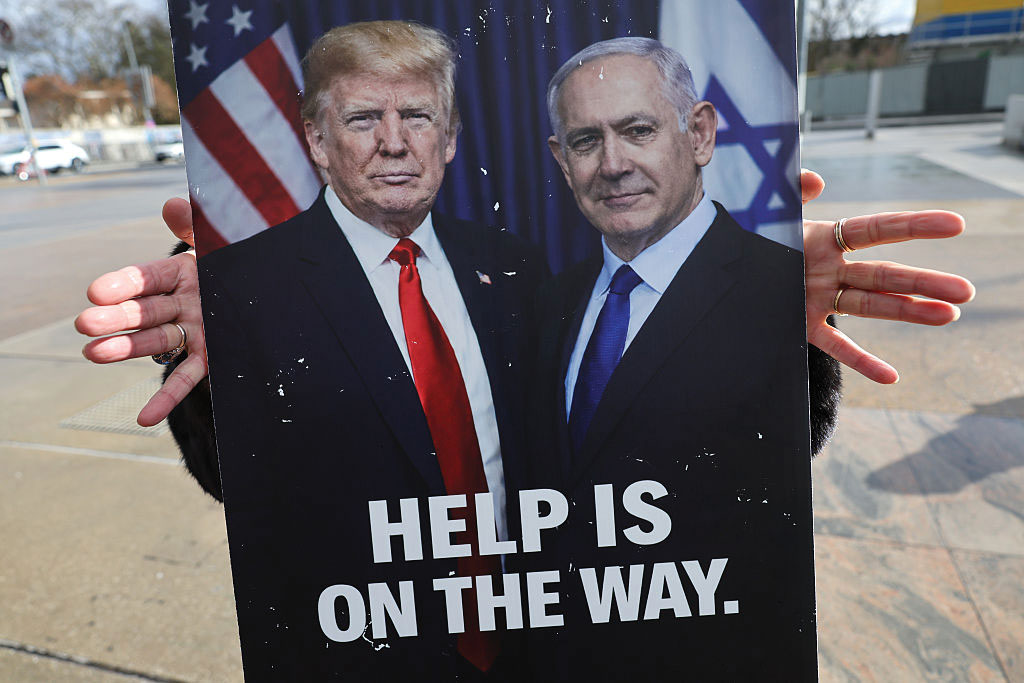

at least that seems to be the problem that prevails

in those who think, “Oh what a rogue and peasant

am I!” like Theseus sailing with black sails,

Jews’ message harming Jews more than the crescent.

In “Can the Hebrew Word for Catastrophic Blunder Be Translated?” mosaic.com 10/19/23, Philologos writes:

Although meḥdal’s emotional resonance, which will now be doubled and redoubled, goes back no further than 1973, the word itself is an old one. It is built on the biblical verb ḥadal, “to cease” or “to cease to be,” which, in the second of these two senses (Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” is lihyot o laḥdol in Hebrew), yields various compound terms. Thus, we have ḥadal-ishim, “ceased-of-person,” a worthless or ineffectual individual; ḥadal-onim, “ceased-of-strength,” someone who is helpless; ḥadal-yesha, “ceased-of-being-rescued,” someone in a hopeless position; ḥadal-pera’on, “ceased-of-repayment” or insolvent, and so on. Ḥidalon, “cessation of being,” denotes in Hebrew a state of near non-existence. One never finds ḥadal used in a positive sense. Theoretically, it is possible to say something like \, “ceased-of-troubles,” that is, unworried or carefree, but in actuality there are no such expressions.

The earliest documented use of mehdal dates to the 10th century. It occurs in the Sefer ha-Mitsvot, the “Book of Commandments,” a rhymed poetic rephrasing of the commandments of the Bible by the great rabbinic leader and religious philosopher Saadya Gaon. In summing up the sin-offering prescribed for transgressions of Mosaic Law, Saadya wrote: He who commits a prohibited act must offer a lamb or a goat to the Heavens [ha-z’vulim]. He who commits such an act unawares must likewise make such an offering. But the Almighty, may He be praised, who pities the poor man, requires of him only turtledoves or pigeons and a tenth [measure of fine flour] for his meḥdalim. The Just One knows the case of the poor [dalim].

Theseus, forgetting his father’s direction, flew a black sail as he returned. Aegeus, in his grief, threw himself from the cliff at Cape Sounion into the Aegean, making Theseus the new king of Athens and giving the sea its name.

Ibn Ezra explains Gen. 13:8:

וטעם ויחדלו לבנות העיר להשלימה כי כבר בנו קצת העיר וקצת המגדל כי כן כתוב אשר בנו בני האדם. או יהיה פירוש אשר בנו בני האדם במחשבתם. וכן וילחם בישראל על בלק. והראשון נכון בעיני.

[AND THEY LEFT OFF TO BUILD THE CITY.] Its meaning is: they left off from completing the city because part of the city and the tower had by this time been built. This is so for Scripture reads, the city and the tower, which the children of men builded (v. 5). It is also possible that the meaning of which the children of men builded is: which the children of men intended to build. Then Balak the son of Zippor, king of Moab, arose and fought against Israel (Josh. 24:9) is similar. The first of these interpretations appeals to me.

Following Ibn Ezra’s interpretation of banu in Gen. 13:8 as “misunderstanding,” I suggest that the mehdal was caused by Israel’s misunderstanding of the significance of the tunnels that Hamas banu, had built, enabling me to recall how the rereading of Isa. 54:13 in bBerakhot 64a can be interpreted as an implied warning that when peace is not great it can be a stumbling block, as sadly proved to be the case regarding the tunnels built by Hamas when its peace with Israel was not great, but a military mirage:

אַל תִּקְרֵי ״בָּנָיִךְ״ אֶלָּא ״בּוֹנָיִךְ״. ״שָׁלוֹם רָב לְאֹהֲבֵי תוֹרָתֶךָ וְאֵין לָמוֹ מִכְשׁוֹל״. Do not read banaykh, your children, but bonayikh, your builders. There should be a great peace for those who love your Torah, and it should be no stumbling block for them.

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.