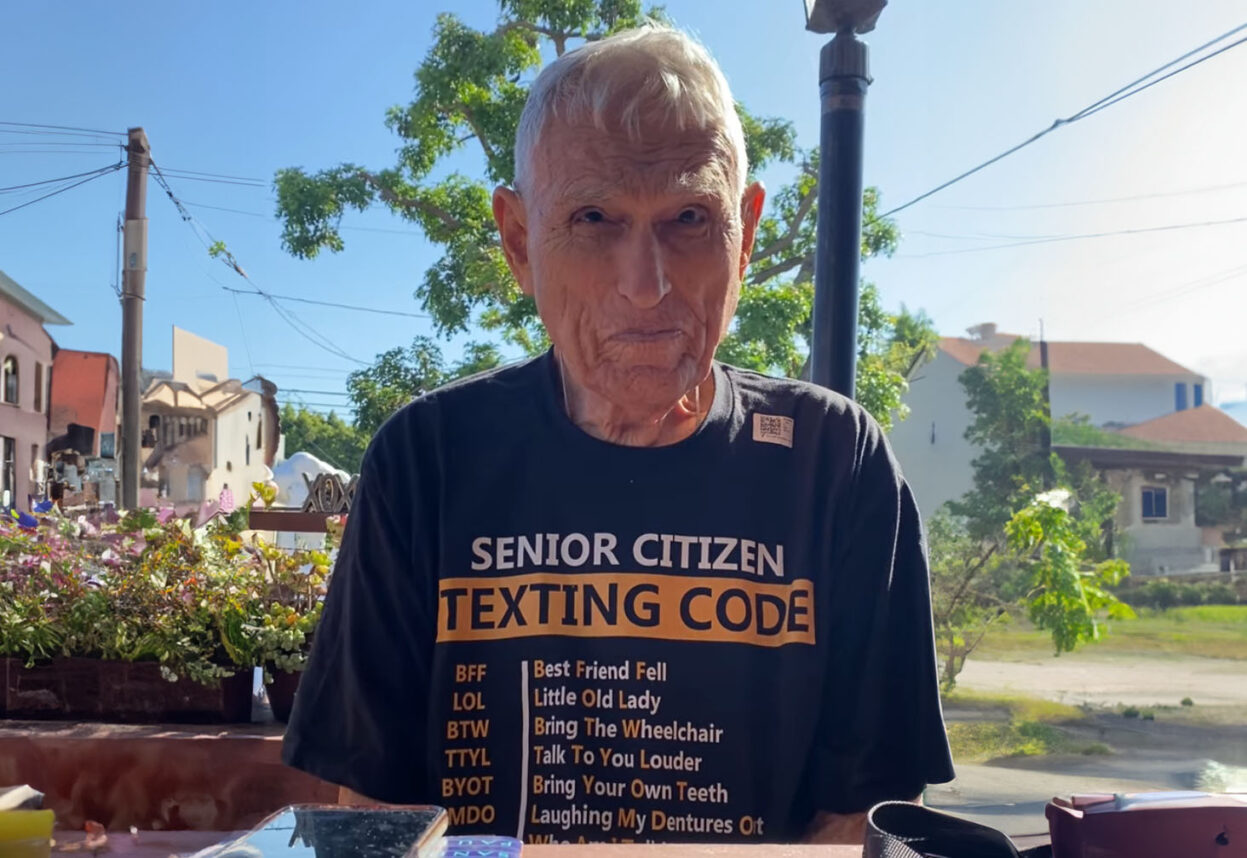

S. Chic Wolk

For S. Chic Wolk, studying at the month-long Summer Program in Yiddish in 1988, then held in Oxford, England, was “a rewarding but expensive” experience.

The Los Angeles resident, who had been raised by Yiddish-speaking immigrant parents in Chicago, was gratified to have his love of Yiddish rekindled. But it cost him, he said, laughing, because he fell under the sway of Dovid Katz, the program’s director.

Wolk remained in touch with Katz. And in 2001, when the Friends of the Vilnius Yiddish Institute was created as an independent, nonprofit educational foundation to support the Vilnius Yiddish Institute, Katz invited Wolk to serve as chairman.

Katz also wanted to find ways to financially assist the elderly survivors in some systematic fashion. Wolk tried, even placing a small ad in The Jewish Journal, but he quickly realized such an undertaking presented too great a logistical challenge.

Eventually he received one call, from Buzby, with each hoping the other would provide a solution. Instead, after much discussion, they agreed to co-found the Survivor Mitzvah Project.

Last spring, Wolk, a retired businessman and the honorary consul of the Kyrgyz Republic, cruised down the Ukraine’s Dnieper River. Along the way, he had the opportunity to meet 10 of the survivors. “To see some of them breaks your heart. You want to send more and more money,” Wolk said.

Sonia Kovitz

The warmth of Sonia Kovitz’s Lithuanian grandparents sparked in her a powerful and lifelong fascination with Eastern European Jewish life.

At 17, Kovitz began learning Russian, eventually earning a doctorate, and also creating collages depicting shtetl life. Later, she studied with professor Dovid Katz at his month-long Summer Program in Yiddish at the Vilnius Yiddish Institute.

Kovitz began volunteering for the Survivor Mitzvah Project initially as a favor to her Los Angeles-based sister, who had taken the family samovar to Buzby to be repaired and had learned about the project’s need for translators. After nine months of occasional help, she was suddenly struck by the immensity of Buzby’s undertaking and its significance for the survivors, and decided to make a deeper commitment.

Fluent in both English and Russian, Kovitz successfully bridges the two cultures and can actually feel the survivors’ level of formality give way to intimacy over time. “They realize we’re not going away,” she said.

Now, about to retire from her job as faculty data project liaison at Ohio State University, she plans to volunteer full time on the Survivor Mitzvah Project, continuing to work via computer from her Columbus, Ohio, home. “This is why I got my doctorate,” she said.

Raisa P.

To save money, Raisa P. moved from Grodno, Belarus, to a village near the Lithuanian border. She lives alone in a hut with three small rooms and broken windows. There’s no indoor plumbing; she trudges outdoors to pump her water from a well or use the outhouse, no matter what the weather.

She saves even more money by growing all her own foods, mostly potatoes and squash. She also raises chickens, collecting the eggs and killing the birds for Shabbat dinners.

But her health is poor. Even though she is only 70 and one of the youngest survivors, she suffers from a bad heart condition and kidney disease. Walking, as well as all that physical labor, is difficult for her.

Raisa does not talk about her family history; she is still clearly traumatized by the war years.

Mera A.

Mera A., 82, is one of only six Jews still residing in the small Lithuanian village of Mariampol and the only one who was raised there. She lives with her son and severely retarded adult daughter, who receives no social service assistance. Her husband died of liver cancer in 1992. Mera suffers from lung and heart problems and walks unsteadily, rarely venturing outside.

Teenage hooligans frequently target Mera and her family in anti-Semitic attacks. Two years ago they destroyed the front door of her first-floor apartment, and she was forced to buy a $500 armored door on credit, later reimbursed by the Survivor Mitzvah Project. The teens also regularly throw eggs at her windows.

When Mera was 8, her mother died. At the start of World War II, her brothers were shot. Mera escaped into Russia, returning to her village in 1959. The Jews who didn’t escape, 8,000 in total, were massacred and thrown into one mass grave. Mera wrote, “Those who witnessed this told us that after that, for three days, the earth in this grave was raising up and down and there was moaning coming out of the grave.”

Mera has money for some food and essentials, and her adult son, who is not working, runs errands for her. But she dreads the anti-Semitic attacks, especially in the winter when the hooligans hurl icy snowballs at her windows on a daily basis, breaking them and letting the snow and cold winds blow inside.

“We wait for the winter with horror,” she said.

Eva K.

Eva K. was 12 years old when her parents and other relatives were murdered in the Holocaust. She suffered through the remaining war years an orphan, still barely able to speak about that period.

Now, 80, and ill with diabetes and other ailments, she can hardly walk. She is alone in her apartment; her daughter, who previously cared for her, died several years ago of leukemia, and her granddaughter, who is studying medicine, moved far away.

Eva has lived in the same apartment in Grodno, Belarus, for 50 years, the entire time without gas or hot water. The landlord promises to install both, but Eva is certain she won’t live to see that day. Meanwhile, the electricity is very costly, as are all her medications.

After receiving her first letter from the Survivor Mitzvah Project two years ago, she wrote: “I am sitting and crying that total strangers care about me.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.