If we could figure out the origin of everyone’s favorite Passover song, it would be enough.

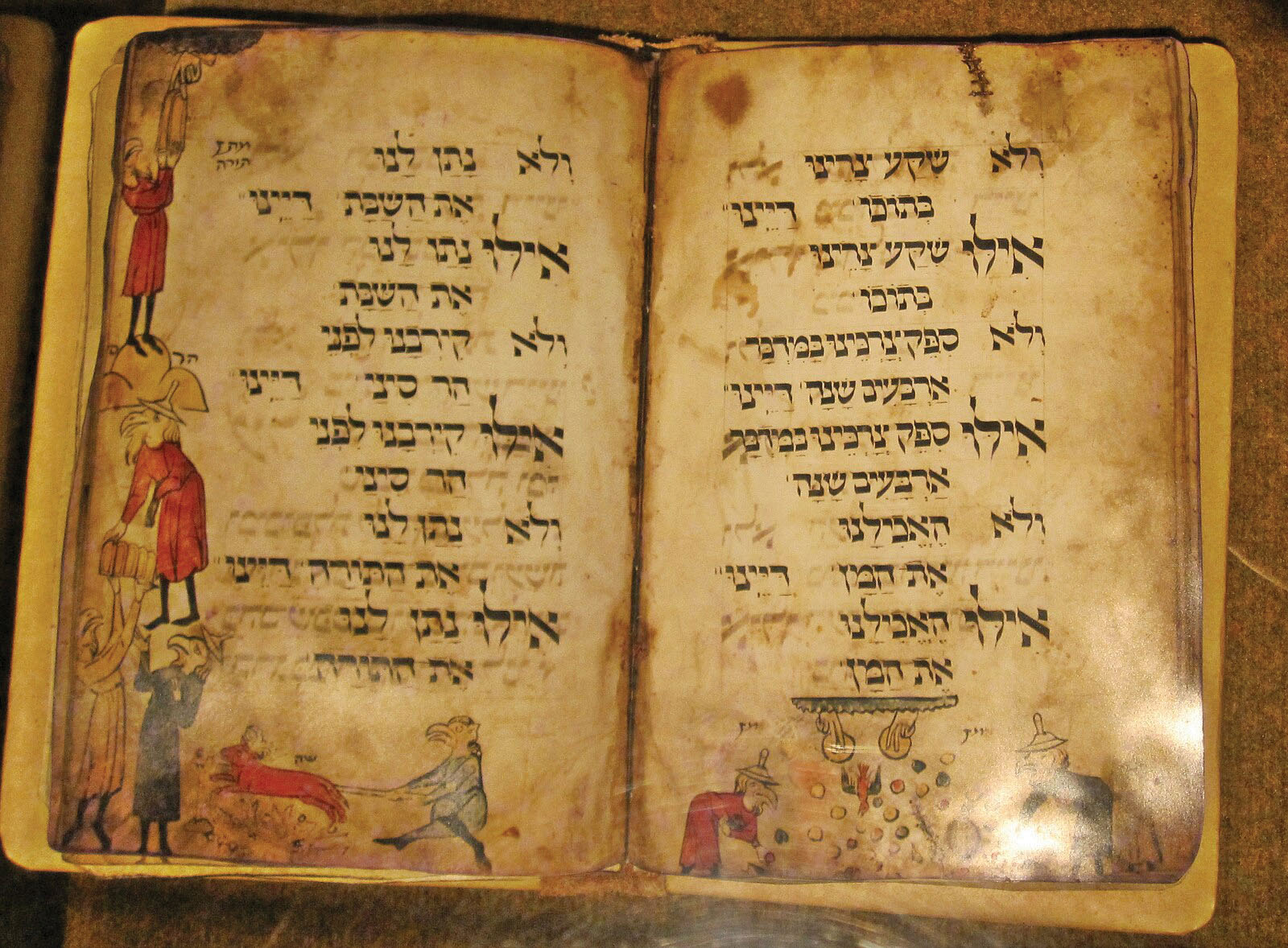

The development of “Dayenu,” that Haggadah ditty that recaps the many miracles the Israelites experienced throughout the Book of Exodus, has puzzled scholars for generations.

The song lists 15 examples of God’s grace. As the Maharal of Prague (1512-1609) noted, they can be divided into three groups of five. The first recaps the Exodus itself (“If He had brought us out from Egypt and not carried out judgements against them … it would have been enough”). The second focuses on the miracles post-liberation (“If He had split the sea for us and had not taken us through it on dry land …”). The third group focuses on the ultimate goal of the freedom granted to the slaves — their covenant with God (“If He had given us the Shabbat and not brought us before Mt. Sinai … If He had given us the Torah and not brought us into the land of Israel … it would have been enough).

Fifteen is a symbolically important number in Judaism. The two-letter name of God, consisting of a Hebrew letter Yud and a Hey numerically adds up to 15, and there are 15 Songs of Ascent in the Book of Psalms corresponding to steps that led from one courtyard to another in the Temple.

But where did this spiritually layered song come from? And when was it composed? Jay Rovner’s new book, “In Every Generation: Studies in the Evolution and Formation of the Passover Haggadah” reviews prior suggestions and offers a new solution. Rovner, manuscript bibliographer emeritus of the library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, notes that “Dayenu”’s composition has been debated for decades. Some suggest it was recited during the Second Temple period as pilgrims presented their first fruits to priests. A midrashic tradition states that when offering the products of one’s labor to God, the Lord will pour out “blessings” in such profusion that your lips will be worn out from declaring “Dayenu beracha,” enough blessings.

Contemporary Israeli scholar Israel Yuval has controversially claimed that “Dayenu” is actually a religious polemic, responding to the second-century bishop Melito of Sardis’ composition of a hymn, “Peri Pascha,” lambasting the Jews for repudiating Jesus and being an ungrateful people. Other modern scholars have argued that the song must have pre-dated Melito’s composition, since it would not make sense for post-destruction-of-the-Temple Jews to have the culmination of the song be about the Temple itself as the capstone of God’s covenantal promise.

Still others offered an early Talmudic era context for its composition, based on its poetic style and its anonymous authorship, a common feature in that era.

Rovner instead argues for “Dayenu” being written in Babylonia prior to the middle of the 9th century. He believes it was inspired by certain midrashim known to the sages at that time that presented the oppressive aspirations of Israel’s enslavers. In a representative example, Mekhilta deRabbi Yishmael, likely composed in the eighth century, suggests that “When Pharaoh saw that Israel had left, he said ‘It would not be worth it for us (‘lo Dayenu’) to pursue Israel, however, on account of the silver and gold they took from us, it would be worth it.”

“In the midrashim, the Egyptian sequence of negative items led to their doom, but ‘Dayenu’ leads their Israelite adversaries in the opposite direction, to salvation and fulfillment,” Rovner writes.

So it was that a song was composed to elaborate on all the positive actions performed by God for His people, “a creative inversion of … Dayenu examples known from classical rabbinic sources associated with the doomed Egyptians’ suffering” from the loss of their money, which, of course, was rightfully due to the Israelites for the centuries of unpaid labor.

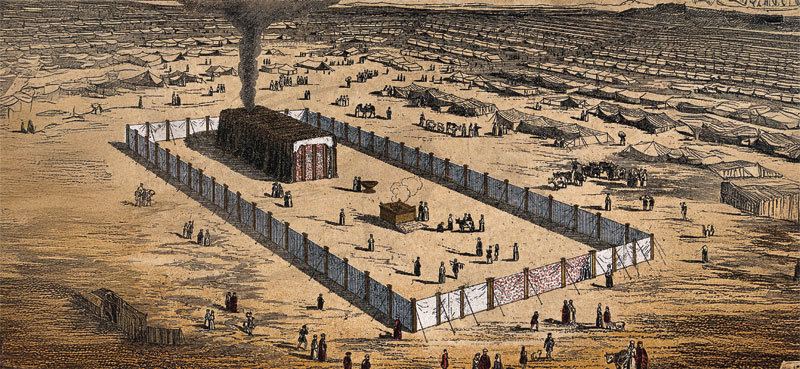

The culmination of the stanzas with gratitude for God’s Temple then, while not a reflection of “Dayenu” being written during the time when the physical Sanctuary stood, is an expression of where ultimate value lies – not in finances but in faith. As our song of collective gratitude expressed yearly at the seder makes clear, the spoils of Egypt were not for physical indulgence but meant to be used to build the Temple, God’s house of spirituality and prayer. Should we merit to live for its eventual rebuilding, it would be more than enough.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.