Bowing to that bovine is something we’ve never lived down.

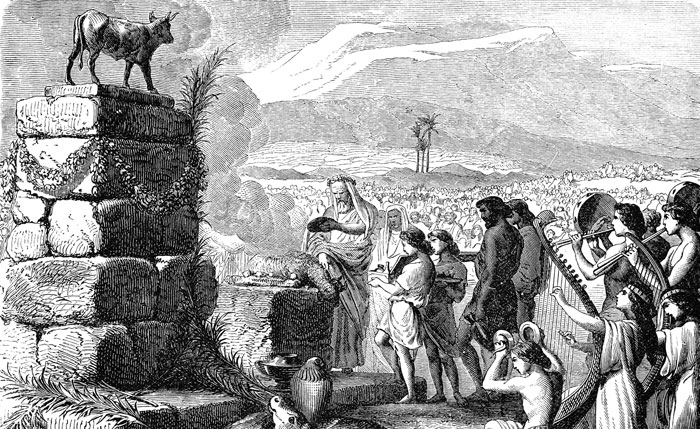

Those popping their heads into synagogue on the 17th of Tammuz – the fast day which falls this year on Tuesday, July 23 – will catch the Torah reading depicting the denouement of the ancient Israelites’ worst sin this side of those smack-talking spies. Worried by Moses’ slow descent from the mountain after carving out those tablet-bearing commandments, the recently liberated slaves crafted and worshiped a Gold Calf and proclaimed it as their new divine emissary.

This, understandably, did not go over well. God got mad. The tablets got tossed.

Having cooled a bit, Moses then composed a desperate plea to stave off the sinning nation’s destruction at the hands of an angry God. God, expressing His grace, also taught Moses a formula for absolution recited on communal fast days ever since, reminding readers both of our failure of faith and our eventual forgiveness, earned by Moses’ prayers.

Perhaps the worship of the Golden Calf takes such primacy of place in Jewish communal memory, serving as the liturgical focus of our fasting, because it’s the antithesis of our founding father’s most lauded triumph, the Akedah, the Binding of Isaac.

The two episodes share some striking similarities.

Both begin with daybreak. Abraham, as Genesis’ 22nd chapter recounts, got up in the morning to saddle his donkey, rising with the sun to set out for the destination God had instructed him in commanding him to sacrifice his son Isaac. The Israelites, too, as the sixth verse in Exodus 32 details, pop out of bed to jumpstart the day – but this time to make sacrificial offerings to their idolatrous creation.

Characters seeing something serves as a major motif in the two tales, both set on mountains. Abraham is told to head to a mountain range that God will show him, and eventually sees the place from afar. He spots a ram stuck in the thicket, and sacrifices it instead of his son after an angel stays Abraham’s hand. He names the mountaintop “The Mountain where the Lord is seen,” immortalized in the name it’s known by today, Mt. Moriah.

The Golden Calf episode, in turn, is also threaded with mentions of characters seeing. It begins with the people seeing that Moses is late coming down Mt. Sinai. Aaron, Moses’ brother, sees the unrest of the people and in a well-intentioned but misguided delay tactic, declares a festival marked by those morning sacrifices. God sees the stiff-neckedness of the Israelites. Moses sees their idolatrous misbehavior.

Both also pivot on characters navigating the oldest of fraught dynamics, that of two brothers. The set-up to the near-sacrifice of Isaac is Abraham’s having to send away Ishmael, Abraham’s other son. After all, as the Bible’s first book makes clear, from Cain killing Abel to the coat-tearing sale of Joseph, two brothers are more likely to battle than break bread together. It’s no wonder, then, that Moses is none too pleased when he shows up and witnesses the damage Aaron has wrought.

Common, too, is the possibility of a populous nation emerging. Abraham, faith having been demonstrated during his trial, is blessed with descendants as numerous as there are stars in the sky. Moses, as he negotiates with God to salvage Abraham’s descendants, is offered by God to be the founder of a replacement nation, swapped in for the Israelites.

It’s quite purposeful then, that in its description of the Golden Calf episode the Torah tips its cap to that earlier episode by using a rare word to describe the heretical revelry indulged in by the Israelites – it states that they got up letzachek, to make merry, from the same etymological root as the name Yitzchak (Isaac), so named because of his mother Sarah’s joy at being told she would have a child. While Isaac’s near death was, thankfully, substituted by a sacrifice, offerings by the cow-kowtowing Israelites result in their own punishment with death.

The Golden Calf, in other words, is the anti-Akedah.

In case the parallels are still in doubt, Moses’ prayer makes the connection explicit. “Remember Abraham, Isaac and Jacob,” he entreats God. Quoting almost verbatim the blessing bestowed on Abraham at Mt. Moriah after the Binding, he continues, “… whom you promised and told you would grant descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky,” descendants who would inherit the Promised Land forever.

Abraham’s faith and family were, in an awe-inspiring act, leveraged by Moses when needed most, ancestral loyalty evoked to save the lives of offspring.

Moses recalling for God the dedication of our religious founders, evoked in the fast days’ Torah portion, is meant as a corrective to our still too-often-rebellious national ways, offering three key lessons.

Remember the sacrifices those who came before us made, the reading reminds us. Even if your great-grandmother didn’t receive a direct call from God to leave her birthplace and head towards Canaan only to then be told to climb up a cliff and risk her entire future, she likely gave up much to give you the opportunities you possess today.

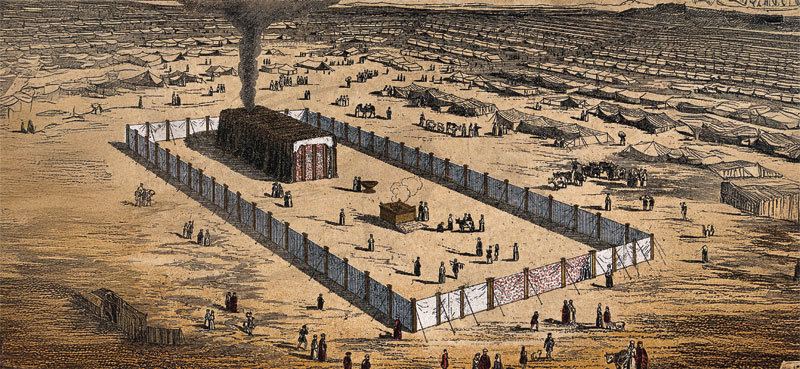

Maintain a sense of brotherhood despite differences, Moses’ eventual reconciliation with Aaron encourages. After all, following their post-Calf spat, the two partnered together on setting up the Tabernacle, ancient Israel’s wilderness Sanctuary, the predecessor to the Temple in Jerusalem. Their building a spiritual home for God course-corrected the fratricidal inclinations Cain had manifested in slaying Abel, and which Isaac and Ishmael had felt.

Lastly, make sure we’re worshiping the right gods. “Everybody worships,” the late novelist David Foster Wallace noted. “The only choice we get is what to worship.” If you forsake ethical religiosity, “pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you.”

So this 17th of Tammuz, we will once more read of a glistening Golden Calf, a reflection of that ever-present proclivity we have for dancing around false deities. Thankfully, Moses’ actions, evoking Abraham’s triumphant moment of faith, will be sure to remind us yet again where true meaning lies.

So this 17th of Tammuz, we will once more read of a glistening Golden Calf, a reflection of that ever-present proclivity we have for dancing around false deities. Thankfully, Moses’ actions, evoking Abraham’s triumphant moment of faith, will be sure to remind us yet again where true meaning lies.

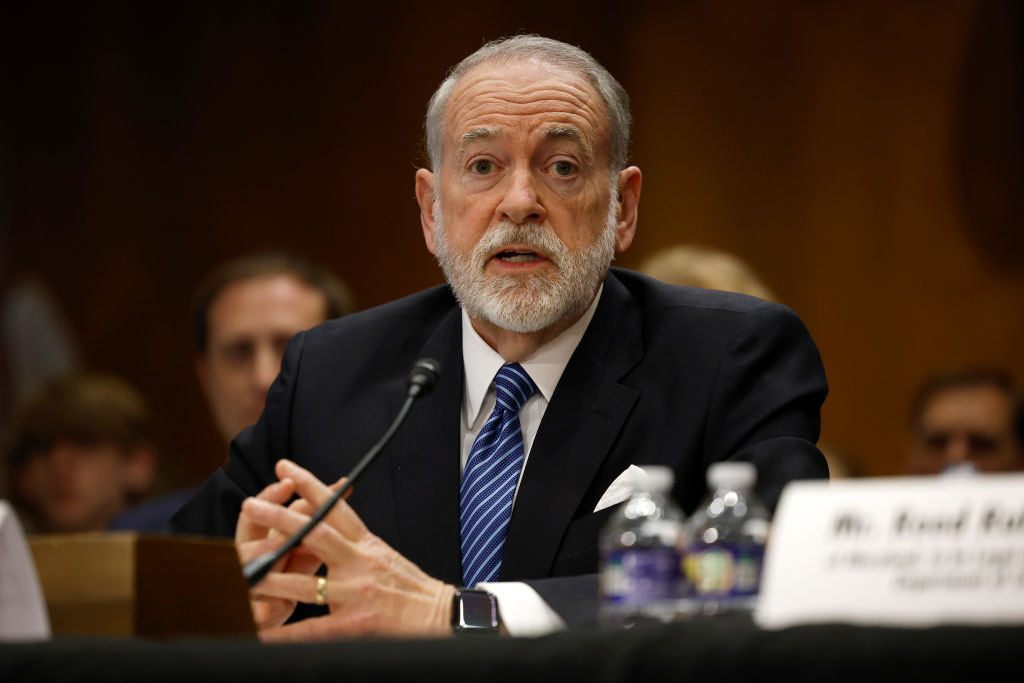

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.