After the Death

Our Torah portion this week, Acharei Mot (After the Death), contains a ritual that bespeaks an ancient stratum of religion, and a deep, tortured chamber of the soul.

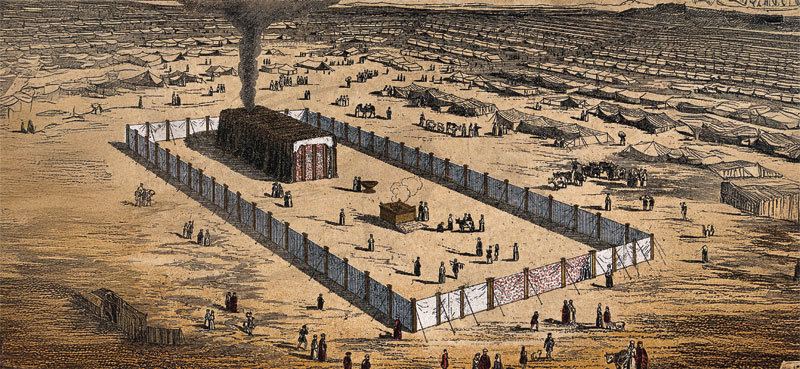

“Aaron will take two goats, and stand them before God at the entrance to the Tent of Meeting. He will place upon them goralot (“fates”), one marked “For God” and one marked “For Azazel” (the desert demon).” Aaron then expiates sin upon the goat for Azazel, and then sends the goat to Azazel, toward the desert.

The other goat, “For God,” is used as a sin offering. Even though we reject animal sacrifice, we can understand a sin offering. If we transgress, we confess, and make an offering. Ever since the destruction of the Temple, the offering is prayer.

But what do we make of the “goat sent to Azazel”, more often called “The (e)Scape-goat.” The Scapegoat brings to the foreground an inner, usually unconscious region that cannot stand to bear a life gone wrong. An ancient, almost forgotten religious idea has us transfer the inner pain of life gone wrong onto the goat sent into the desert, to the Demon – that Demon perhaps was understood as the actual source of unbearable inner pain.

Without this ritual – and believing in this ritual – we find other ways to discharge our inner pain – on to other people, for example, individuals or groups. The great American thinker Kenneth Burke (1897-1993) (whose fine works range across the humanities and social sciences) coined the term in 1935 in his book Permanence and Change. In that fascinating book, he discusses the experience of “incongruity” – who I am, what my life should be like – is incongruous with how I am, what my life is like now. One might say that a wise and psychologically mature person sees the self, and the self with others, in a constant process of change, and that we each have some degree of power to achieve a better vision of ourselves. We work toward the future. We also have some degree of power to transform with others, and the world. With what we cannot change, as Reinhold Niebuhr taught, we might aim toward serenity. Lacking that, wise acceptance, I would say.

A less psychologically mature person sees the present as “permanent” and looks for simple causes upon which to heap blame – in essence, to scapegoat. Like in the ancient ritual, one’s own inner dis-ease is placed upon the goat, and the goat is sent to the Demon. Without the belief that we can ritually discharge inner pain, we send that inner disorder onto others. In order to avoid self-hatred (or along with it), our psychological mechanism is to displace our inner “permanent dis-ease” outside of us, and try to annihilate that external cause and send that external cause to hell (often with specifics directions). Mostly we use words. Sometimes we actually kill.

Hence, hatred and haters, and I say this with a heavy heart. This tendency to place our inner pain onto others leads to hatred haters of all types – spewers of venom, ideological bigots, from the societal to the interpersonal. Scapegoating leads from the painful reality of verbal abuse and hatred in the family and civic spheres, all the way over to purveyors of putrescent prejudice, a warping of the spirit that sinks into the minds of shooters and bombers.

Every hatred is different, I know – hatred of Jews, Muslims, and Christians, hatred of the right and of the left – every hater and group of haters has their reasons. And every hatred is the same. The commandment not to hate in next week’s Torah portion is all encompassing, just as is the commandment to love.

When our psyche is under unbearable stress, we have an existential decision to make. We place the goral, the fate, upon ourselves: to God, or to the Demon? Sink into hatred or arc into love?

John Oxenham wrote in 1913,

To every man there openeth, a way, and ways, and a way,

And the high soul climbs the high way,

And the low soul gropes the low.

And in between, on the misty flats, the rest drift to and fro,

But to every man there openeth a high way and a low;

And every man decideth the way his soul will go.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.