What does God require of you? Only to do justice, to love compassion and walk humbly with your God.

“It’s on my wall,” said Rabbi Denise Eger, pointing to the spot in her office where her favorite Bible verse is written (also transcribed on her tallit). “Prophet Micah, Chapter 6, Verse 8. It’s really a reminder of what our human tasks are.”

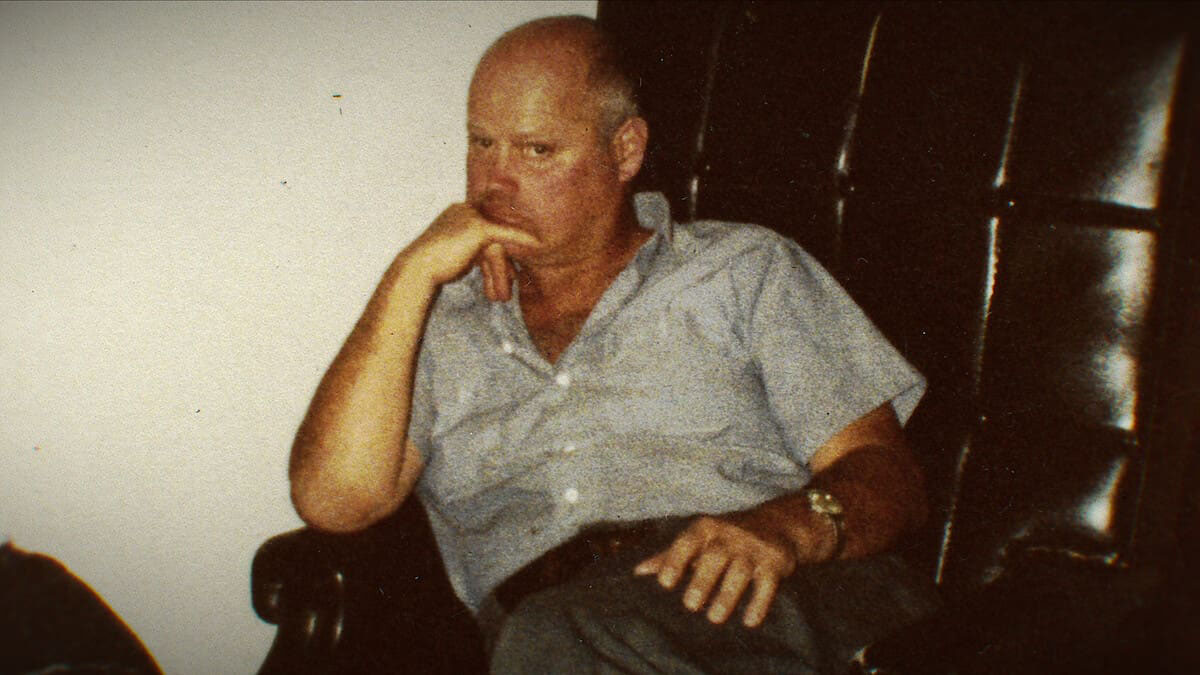

They are tasks she will have a chance to tackle on a large scale as the new president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), the largest and oldest rabbinical organization in North America. When she takes the helm of the 126-year-old Reform organization March 16, at age 55, she will be its third woman and first openly gay leader.

Meeting in the LGBT-friendly West Hollywood synagogue Kol Ami, of which she is the founding rabbi, Eger — a longtime activist on many fronts — said her goal as CCAR president is to make Judaism bigger, more accepting and more inviting.

“We have to open the doors wider, and open the tent wider, and open the synagogue wider, and open the JCC wider, and open the Federations wider. So that’s my goal to help Jews become more Jewish — to open the doors wider,” she said.

Rabbi Steve Fox, CCAR chief executive, said he’s “extremely excited” about Eger becoming president, particularly because she’s been a strong leader and crusader for human rights.

“It’s also very meaningful for the rabbinate that we have elected our first openly LGBT president at a very historic moment in time,” he said.

In 1977, CCAR passed its first resolution calling for human rights for homosexuals, demanding the end to discrimination against members of the LGBT community. It later advocated for the ordination of openly gay rabbis and affirmed the right of a rabbi to officiate at an LGBT wedding.

But sexual orientation isn’t all that defines Eger. Talking to her is like talking with a family friend — easy and relaxed. Every so often, in a moment of inspired enthusiasm, her face lights up and she speaks passionately, like she’s in the midst of reciting the best part of a sermon.

In typical rabbinical fashion, Eger speaks in call-and-response, repeating the questions that are asked to her before responding. Asked which biblical character she’d like to spend time with, she throws the question right back at you before answering decidedly: Deborah.

“You know, she’s pretty cool,” Eger said. “She sat under this palm tree and people came to her for advice and counsel and, supposedly like the oracle of Delphi, she gave pronouncements. But she was also a general, so here was this really gutsy woman in a time when women did not do those kinds of things, and she had her finger on the pulse of the nation.

“And I think it’d be really cool to sit under her palm tree with her, have a little cafe au lait or a cup of tea and hear her reflect on her take on leadership … and on the role of women.”

Eger grew up in Memphis, Tenn., in a close-knit Southern Jewish community, which was smaller and less fragmented than the one she later found in Los Angeles.

“The South is a great place to be Jewish, because it’s a tight Jewish community,” she said. “Whether you’re in Atlanta or Memphis or Nashville or New Orleans, the Jewish community is very interrelated, very family.”

With the South as her backdrop, Eger was raised in the belly of human-rights activism. She remembers driving her mother to work on Beale Street, where her cousins owned a business, and sitting outside of the Lorraine Hotel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was shot.

“Now it’s the National Civil Rights Museum, but at the time, it was a crumbling slum mess. It had fallen into disrepair and disarray in a terrible neighborhood in town — urban blight — and I used to sit there and think, ‘How could this great man have been assassinated? What in our country could lead to such horror?’ And really that inspired me along the way to say that my Judaism was going to be a vehicle for helping others, to lift up those who felt ‘other.’ ”

Eger knew what it felt like to be an outsider from the time she was 12.

“I knew that I was a lesbian, and it was the South and it was very formal and there was no room for that. It was a different time, you couldn’t talk about it, you had to remain hidden, so that’s where I felt out of step,” Eger explained.

But for her, the synagogue was a place of refuge, “of great safety and continuity for me.” It was about this same time that she decided she wanted to have a Jewish profession. Originally, she thought she’d be a cantor but decided during her sophomore year in college to become a rabbi. So she transferred from Memphis State University, where she was a voice major, to USC, which had a joint program of religion and Jewish studies with Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. In 1988, she was ordained a rabbi.

For many of Kol Ami’s congregants, largely composed of local Russian and LGBT communities, this is their first time returning after many years of avoiding synagogue because of a fractured relationship with their inherited religion, whether it be for personal or political reasons.

“There’s always an ‘other,’ so I think that I’ve been taught both by parents and my rabbis and teachers what it means to help lift up the voices. And that’s one reason we’re Kol Ami, ‘voice of my people,’ ” Eger said.

People of all sorts find their way to the congregation — and Eger. Fifteen years ago, Wendy Goldman was between congregations after her rabbi retired and her mother passed away. “I wanted a place to grieve and find spiritual renewal,” she said.

So Goldman turned to Kol Ami and, although she identifies as a straight woman, she never felt out of place in the primarily LGBT congregation. Later, when she was in the hospital, she remembers the relief she felt upon seeing Eger at her side during a trying time.

“Groggy from the anesthetic, I opened my eyes to see [Eger] sitting at my bedside, helping me to have courage to face the recovery I was facing,” she said. “She is truly a special person to me.”

Located across the street from a hyper-developed stretch of high-rises, retail chains and grocery stores, Kol Ami got its start in 1992. Back then, the neighborhood was, to put it nicely, downright sketchy — so much so that contractors chose to have the main doors for the congregation in the back, accessible via the parking lot.

“It’s now a lovely residential neighborhood,” said Eger, who called the synagogue a “mitzvah” of urban development, explaining that, as the first new building on the block, it helped spark what followed.

Her accomplishments as a mouthpiece for human rights are extensive. Eger is a spokeswoman for the LGBT community, sitting on the boards of countless organizations, promoting AIDS awareness, equal marriage rights and basic civil rights. She was the first woman and openly gay president of the Southern California Board of Rabbis, blogs regularly for the Huffington Post and has received numerous awards. (She’s also engaged to be married and the proud mother to Benjamin, who is in college.)

Much of her activism, she said, is inspired by her own childhood Memphis rabbis, who staged marches and protests during a tumultuous time in the civil rights era.

One of those role models was Rabbi Harry Danziger of Temple Israel in Memphis, who served a term as president of CCAR a decade ago. In particular, Danziger said he remembers Eger’s confirmation, which is typically a formal ceremony. Acoustic guitar in hand, she opted to sing Joni Mitchell’s folk ballad “The Circle Game.”

“I take enormous pride in her becoming president, but more, I take pride in the rabbi and human being she has become,” Danziger said. “It is an honor to have been her rabbi and to be her predecessor as president of the CCAR, which is such a force for Jewish continuity and tikkun olam.”

For all her metaphorical talk about opening doors wider in the Jewish community and beyond, circumstances are making that happen literally. This past July, a stolen Tesla crashed into Kol Ami’s edifice, and now part of the building remains boarded up.

So what’s the No. 1 item on Kol Ami’s to-do list? Literally opening the doors wider.

“We’ve known we wanted to change the front entryway for a while now. I didn’t think it would happen by a car crash into a building,” Eger said.

It’s symbolic of her larger plans.

“Imagination is the greatest gift from God that we have, and what a sin it is if we don’t try and use it,” she said. “And now we have to imagine, what’s the future of Judaism going to look like. What can we make it look like?”

And that’s why she’s excited to be president of CCAR — “because I’ll be in a position to do that imagining in a larger scale.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.