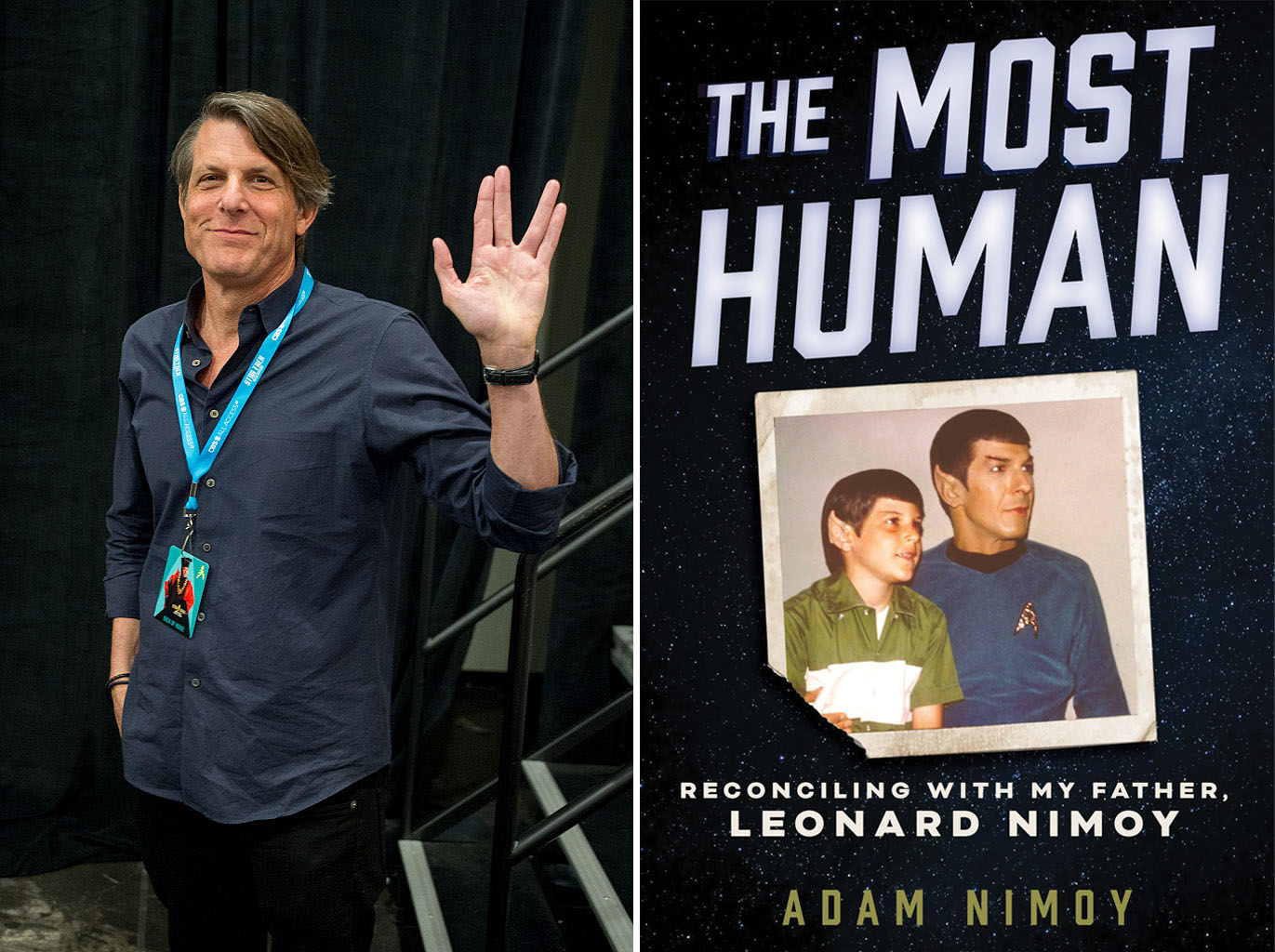

If you think you need to be a Trekkie to care about Adam Nimoy’s memoir “The Most Human,” you don’t. You also don’t need to be Jewish, sober or estranged from your father.

Adam’s father was Leonard Nimoy. Yes, that Leonard Nimoy — Mister Spock to the millions of “Star Trek” fans. But in “The Most Human,” Adam describes his father, who passed away in 2015 at age 83, as a hard man to love, and even harder to get love from. Adam’s book is a patient, painful reckoning with cycles of trauma, addiction, estrangement and reconciliation. Even if you’re just someone trying to figure out how to forgive a parent without forgetting what they did — this book lands like a long exhale after holding your breath for too many years.

If you’re browsing for a Father’s Day gift, this one is for anyone staring down family patterns and wondering if it’s too late to change. Nimoy’s story doesn’t offer easy resolutions, but it does offer something better: the tools and conversation examples to start again. “Everybody who reads this says that they didn’t know that side of Leonard, they got to know him a little bit better,” Adam said. “He’s this iconic character, and this book brings more of his personality as a dad into focus.”

The book begins in a synagogue on Yom Kippur. Adam recalls sitting in the back row as his father was called to the bimah to chant the story of Jonah. The moment is brief but revealing. Jonah, the prophet who runs from his calling and winds up in the belly of a whale, becomes a spiritual mirror for Adam: a man who spent years hiding behind pot smoke and emotional avoidance. “I knew something about that,” Adam writes, noting how long it took him to stop fleeing from the discomfort of family, responsibility and reconciliation.

When asked what he learned from writing the book, Adam said that he gained a lot more empathy for his father. As the son of Russian Jewish immigrants growing up in Boston, Leonard was raised to feel desperate to survive. He came to Hollywood with no money, little support and no major connections. His parents were angry that he wanted to become an actor.

The echoes of Leonard’s career never disappear. Adam sees performance everywhere: in the classroom, in the director’s chair, even at Comic-Con and Star Trek events. But Spock, too, was shaped by Leonard’s past — as the child of immigrants, as the outsider, as the person trying to belong without betraying himself.

“There was a lot of conflict with him,” Adam said. “He was very difficult to deal with. And I say we didn’t have the tools to deal with any of the conflicts so that when issues would arise between us, it never went well.”

The book is filled with raw moments: childhood memories where Leonard is in the room, but not present; a six-page letter from Leonard to Adam that easily could have torpedoed anyone’s relationship for life; and stinging moments like the time that Adam sent his father an old production still from his father’s role as Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof.”

“My dad wrote me an email in response thanking me for the [‘Fiddler on the Roof’] photograph and also wishing me a Happy Father’s Day, and then informing me that he believed that ‘unconditional love was a fantasy.’”

For a story that takes place primarily in Hollywood, there’s little celebrity name-dropping. Rather, it’s a book about looking back and naming what-happened. And what happened, often, was silence. Adam said that when he shares his story anonymously at 12-step meetings, people are inspired to try to reach out to a parent or a sibling.

“Acceptance is not approval,” Adam said. “Accepting my dad for who he was doesn’t mean I approve of everything he did. It’s just that I accept him for who he is.”

Adam said he learned to give his father some slack. That slack becomes the book’s spiritual arc. And it’s grounded — literally — in Jewish time and Jewish space. Shabbat dinners become the first step back into the relationship. Adam starts attending services at Beit T’Shuvah, a synagogue and addiction recovery center on Venice Boulevard. “The cycle of dysfunction is not new, but how to break the cycle is really what the objective is,” Adam said.

Recovery concepts like “detachment with love” and “living amends” are central to the story arc. Where Leonard once denied affection, Adam gave it. Where his father shut down, Adam leaned in and tried to become someone his own children, Maddie and Jonah, could trust.

Adam writes that the dysfunction between fathers and sons didn’t start in the Nimoy house. It started with Abraham and Isaac. With Jacob and Esau. With Joseph and his brothers. The question isn’t so much whether pain will travel down the family tree, the question is whether someone, anyone, will do the hard work of pruning it back. Throughout the book, Torah references stretch beyond the patriarchs. Jonah and the whale gets pulled in as a tale of finally stopping to listen in the midst of chaos. T’shuvah (“the process of returning”), l’dor v’dor (“from generation to generation), and tikkun olam (“repairing the world”) are all featured along Adam’s journey.

Adam’s late mother, Sandra Zober, also looms large in the book, culminating with her final days spent bedridden, pill-dependent and fiercely opinionated as ever.

Anyone who’s ever stared down a closed door and wondered if knocking one more time would matter will find this book enjoyable. It’s well-written, the audiobook is everything an author should strive to do when reading their memoir — you can really hear in Adam’s voice what he’s feeling. Parents who struggle to show up emotionally will find this book relatable, and kids who are tired of waiting will find it to be a gateway to healing those bonds.

Adam shares his story not from a Hollywood high horse as the offspring of a world-worshiped cultural icon, but as the bearer of something much harder to gift: emotional clarity, spiritual honesty and the exact kind of story you should hand your father on Sunday, if only to say: “I see you. I read this I’m trying, too.”

If you’re looking for a memoir about reconciling with a complicated parent, this is one of the most emotionally grounded and engaging that I’ve read. This would make a meaningful gift for anyone in recovery, or anyone trying to make peace with family history. Readers interested in spiritual memoirs, Jewish reflection or family repair will find something familiar and worthwhile here.