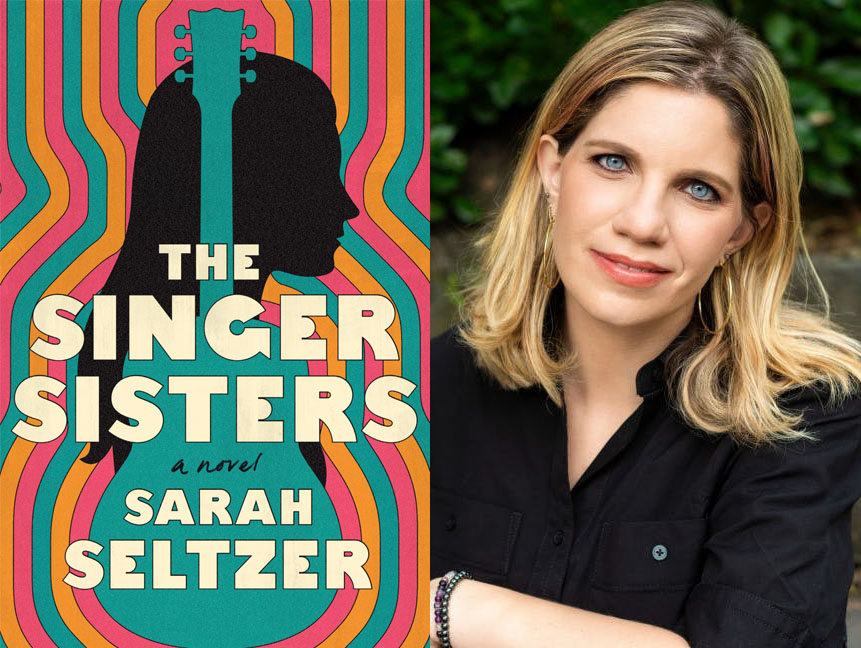

How would you feel if you knew, and everyone knew, that you were the most talented person in your family, but instead of using your gift, you found yourself making dinners, changing diapers, waiting for your cheating husband to come home, waiting for the superintendent to change the lightbulb, waiting for your kids to grow up. What if, despite big dreams, what you are, in the end, seems to be always in relation to your relations: You are the wife, mother, lover and sister of successful singers. No matter that they sing the songs you wrote or that they wrote about you. On the grand stage, you take no part.

In her fifties, Judie Zingerman, one of the “Singer Sisters” of Sarah Seltzer’s debut novel of the same name, looks back at her life and sees “a stack of mistakes, bumbles, bungles, errors, grave misjudgements, screwups, and wild turns.” But as we follow her life—along with that of her daughter, Emma Cantor—we see something different.

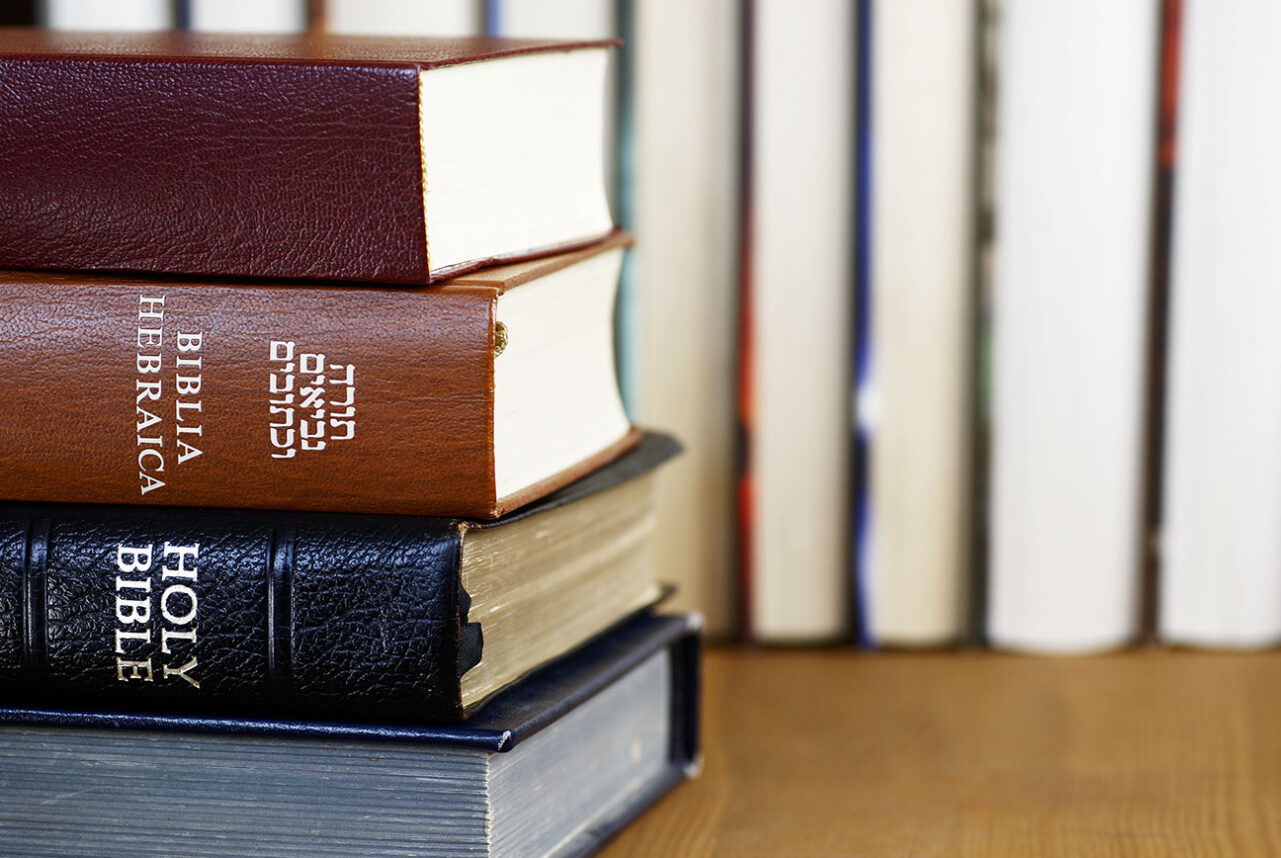

Judie and her sister Sylvia grow up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When we enter their home, it is a typical Jewish American home of the 1960s: The family sits together at the Shabbat table after lighting candles and washing hands. The smells are of yeasty challah and salty soup. The room features a portrait of Eleanor Roosevelt, marking the family’s loyalty to the country, and a silver tea samovar, indicating their European origin. Judie and Sylvia, we read, are being raised to be “good girls.” Later, we find little of the Jewishness that marks the early section. In the late ’60s through the 1970s, for instance, Judie calls for prayer for the children of Cambodia and Vietnam (she prays kneeling, hands in the air), as the Six-Day War and Yom Kippur War pass, unmentioned. Still, in the home of their parents, Hyman and Anna Zingerman, the girls are considered the “homegrown prodigies” of their Jewish community.

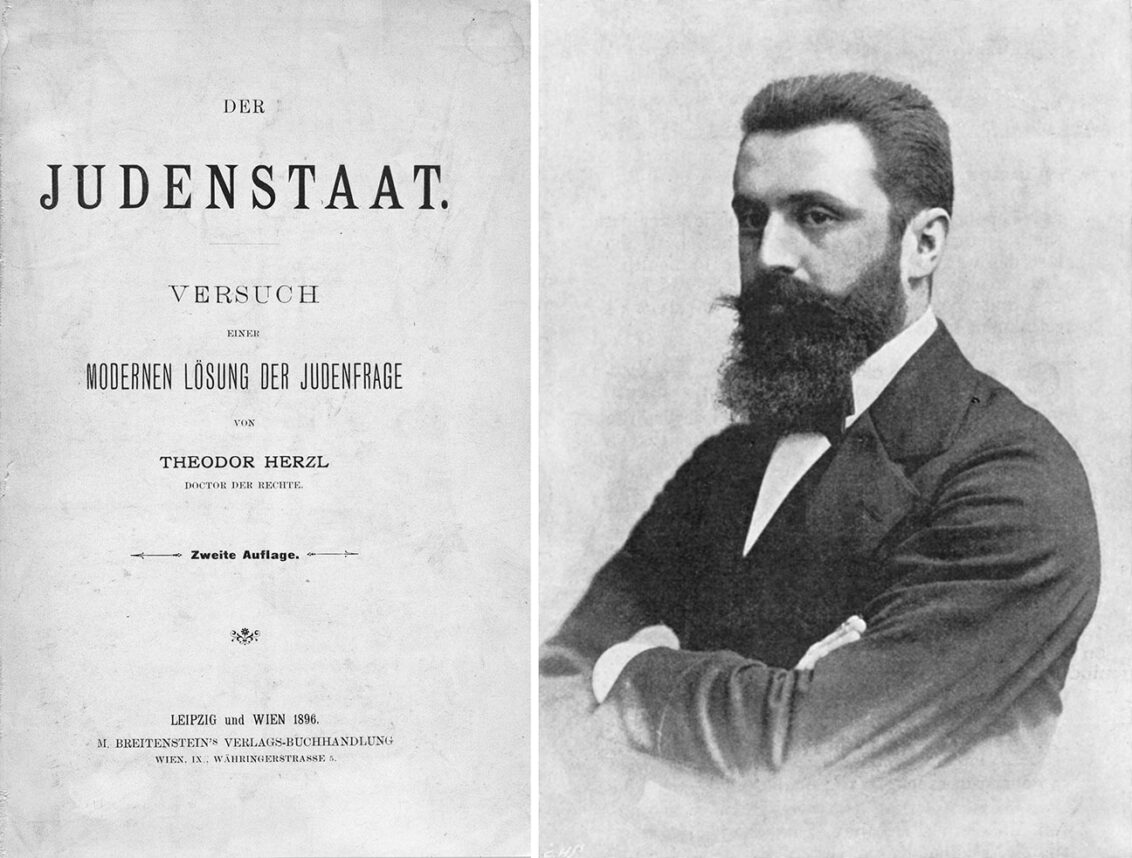

But 18-year-old Judie, passionate, determined, striving to be more than a singer at the synagogue concerts, takes off to the most exciting place in the world: New York City. “We have to become famous singers,” she tells her sister. She packs birth control pills and a guitar and boards a Greyhound bus, heading to Greenwich Village. She follows a boy who once visited their Shabbat table, David Cantor, who, like the Zingermans, de-ethnicizes his name, in this case to Canticle (that Seltzer has given them the names Zingerman and Cantor suggests she had fun with nominative determinism). We know, because the book opens with their divorce, that Judie will marry Dave, and that through this marriage, she will become the woman that we first meet through her daughter’s eyes, one who did “one absurd thing after another in life,” a path Emma is keen not to take.

What Emma can’t see from her position as disgruntled daughter is that the details, from that first package of birth control pills to Judie sharing her lyrics with Dave before knowing if she could trust him (spoiler: he steals them), are what make a life. If Judie’s choices amount to “one absurd thing after another,” so do all our choices. What can anyone do but try, even if trying often means failing?

Emma, familiar Emma, the character of my own generation, is whiny—by design. Seltzer keeps a tight lid on our sympathy for her. She’s like her mother before her, a young woman trying to make it big, but lacking her mother’s talent. And she’s like her father before her, unafraid to take lyrics from her mother when she can’t come up with any as good. But she also serves as a keen reminder of how hard it is to understand those who came before us, particularly our mothers.

Perhaps because I lived through the ’90s and thus the music of Jewel and the Spice Girls, I found myself more drawn to the chapters from the 1960s and ’70s, even though many of these sections illustrated the precarious positions of women at the time. Abortions were illegal. Lesbians felt forced to pass as straight. There was faith that “We’re about to get an Equal Rights Amendment,” but the reader knows better. Maternal advice consisted of: “Do better,” and the confession that “Women don’t have much choice in life.” Judie declares, “No one important hears you unless your music speaks to men.” Seltzer, an editor at Lilith Magazine, is incredibly strong on gender issues.

“The Singer Sisters” is fast-paced and submerges the reader into a musical family, a musical world. I often sang to myself, reading it (unfortunately, Jewel’s “You Were Meant for Me” made it into my mental loop, but so did some Dylan and “Hineh Ma Tov”). I also marveled at Seltzer’s ability to move me among storylines and time frames and musical eras and never lose me; I was hooked beginning to end.

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”