Most Americans of a certain age still remember where they were when John F. Kennedy was killed in November 1963. But nearly all Iranian Jews who were alive on the eve of the Iranian Revolution remember May 9, 1979—the day that Habib Elghanian, Iran’s most prominent Jewish leader, was brutally executed. His murder, unimaginable before the Revolution, was a critical event that delineated the beginning of the end of 2,700 years of continuous Jewish presence in the country that, until 1935, was known as Persia.

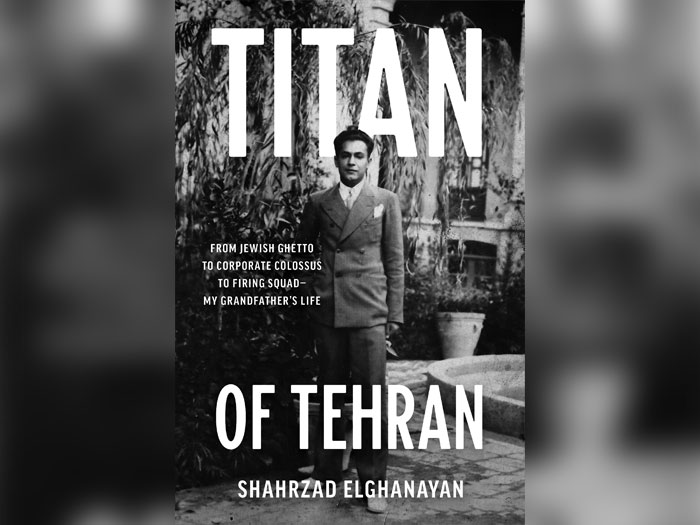

That May evening in New York City, seven-year-old Shahrzad Elghanayan was asleep in bed when her family heard news of her grandfather’s death via a shortwave radio broadcast of news from Iran. Elghanayan, an award-winning journalist who currently serves as a senior photo editor for NBC News, captures the vibrant life and unjust demise of her legendary grandfather in the meticulously well-researched book, “Titan of Tehran: From Jewish Ghetto to Corporate Colossus to Firing Squad—My Grandfather’s Life” (Associated Press).

“While our black shortwave [radio] droned on in the cold marble bathroom, my grandfather’s bullet-riddled body languished in the prison morgue, with a cardboard sign around his neck. It read: ‘Habib Elghanian, Zionist Spy,’” Elghanayan writes. The next day was the one-year anniversary, or yahrzeit, of the death of her grandmother, Habib’s wife, whom the family called Nikkou Jan. As Elghanayan notes, “The family began mourning my grandfather… even as it was marked by my grandmother’s yahrzeit.”

Shahrzad, her brother, and their mother and father moved to the United States in 1977 because her father, Karmel, didn’t want to raise the children in Iran. In 1975, four years before the Islamic Revolution that brought Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to power and transformed Iran into a fanatic theocracy, Iran’s secular leader, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, arrested her grandfather and imprisoned him for months, using Habib as a scapegoat for the country’s economic corruption. But Khomeini, a decade before gaining power in Iran, already had his eye on Habib.

“It [Islam] is the country’s independence … the entire country’s economy now lies in Israel’s hands; that is to say it has been seized by Israeli agents.”

In her research, Elghanayan found a footnote to Khomeini’s speech that read, “The Thabit Pasal and Elqaniyan families were among those mediators of world Zionism who resided in Iran.”

In her research, Elghanayan found a footnote to Khomeini’s speech that read, “The Thabit Pasal and Elqaniyan families were among those mediators of world Zionism who resided in Iran.”

Only five years old when she left Iran, Elghanayan didn’t have a chance to grow close with her paternal grandfather, but after his execution, the injustice of his death stayed with her. And then, on November 18, 2010, Elghanayan read a front-page article in The New York Times that changed everything. The story focused on a computer virus called Stuxnet that sabotaged some of Iran’s nuclear capability. Hackers, presumably from Israel, had left a strange number in the program: 19790509. That was the date that Habib Elghanian was executed in Tehran.

“Had Israel kept my grandfather’s execution on a secret list of wrongs against Jews that it would never forget?” writes Elghanayan in the book.

Shortly after, she left her job as a news photo editor for the Associated Press (AP) and began the decade-long research and writing process that took her to Ohio, California and Israel to interview over 30 people who knew Habib, including relatives, business partners, community leaders, historians, diplomats, activists and other experts on Iran. “The New York Times article showed what a long shadow my grandfather still cast decades after his execution, and that was the spark,” Elghanayan told the Journal. Her mission was invaluable: “Digging for every shred and shard” about Habib’s life. “I set out to resurrect my grandfather’s bullet-shattered life with glistening new veins,” she writes.

Habib Elghanian was the first Iranian civilian executed after the revolution, and he was also the first Jew.

Habib Elghanian was the first Iranian civilian executed after the revolution, and he was also the first Jew. Part-millionaire businessman and part-community leader, he was an Iranian Andrew Carnegie who modernized the country beyond recognition. He gave generously to charities in Israel, including Magbit, but also helped countless causes in Iran.

A self-made entrepreneur who grew up in Tehran’s ghettoized Jewish quarter, in an area Elghanayan calls sar-e-chal, or “the edge of the pit,” Habib (born “Habibollah,” or “God’s beloved,” in 1912), began trading second-hand clothing and watches as a youth. Together, he and his six brothers worked their knuckles bare to earn anything that would extract them from poverty, disease and, on a few occasions, violent riots inside Tehran’s mahalleh, or Jewish ghetto. After decades of hard work, Habib became a pioneer in fields ranging from mining and real estate to construction and aluminum. But it was the plastics industry and his company, Plasco, that made him among the most accomplished businessmen and philanthropists in twentieth-century Iran. Habib introduced the plastics industry to the country and changed the Tehran skyline, constructing Iran’s first private-sector high rise, known as the Plasco Building, in 1962. Thanks in part to Habib Elghanian, Iran transformed from a country that imported goods to one that manufactured them.

But he also assumed the role of a secular leader who, beginning in 1959, spoke on behalf of 100,000 Iranian Jews. Habib’s accomplishments brought indescribable pride to the country’s Jewish community. Out of the 5,000-6,000 Jews who lived in Tehran’s Jewish quarter, his parents were among the poorest. Habib overcame World War I, a famine, typhus and cholera outbreaks, and a worldwide influenza pandemic. He was a luminous symbol of modern Iranian Jewry, and access to education changed his life. Habib attended the first Iranian school for Jews, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, where he and most Iranian Jews received a secular education in addition to a Jewish one.

In this way, he and tens of thousands of other Iranian Jews enjoyed greater assimilation and felt truly at home in Iran. This might explain why Habib decided to stay in Iran even after the fanatic violence of the revolution. Friends and relatives begged him to leave, but he stubbornly responded that he was a proud Iranian; Iran was his homeland.

Habib was arrested in March 1979 and tortured in prison; the last image Iranians saw of him was one published in newspapers all over the country: Pleading for his life at a sham trial that lasted 20 minutes. The legendary titan — larger-than-life, amiable and always impeccably dressed — appeared small and meek in the throes of what his granddaughter calls “a killing machine fueled by irrational, vengeful cruelty, its movements running counter to logic, decency and custom.”

Habib, whose extraordinary business acumen was matched by his philanthropy, was charged with being a “Zionist spy,” shot and buried without any ceremony in Tehran’s Beheshtieh cemetery, with just enough men for a minyan.

Even attending his funeral could have put mourners at risk of being accused of Zionism, which, after the revolution, was and remains punishable by death. The car carrying Habib’s body drove past his iconic Plasco and Aluminum buildings one last time. It was driven by Mikail Loghman, a lifelong friend and director of Beheshtieh Jewish cemetery. The guard who delivered Habib’s body from the morgue demanded compensation for each bullet.

The way in which Elghanayan details her grandfather’s gruesome death is at times gut-wrenching, but her career in journalism proved indispensable to her painful research.

“Shortly after I started working at the AP, I was on the war desk during the Iraq War in 2003,” she told the Journal. “As a news photo editor, I’ve seen a lot of graphic images of death not only from conflict zones but also from natural disasters. If you want to be a good journalist and tell victims’ stories, you can’t let your feelings paralyze you. You have to push beyond that, knowing that you’re telling the world their story and memorializing the victim.”

Elghanayan and her family may have left Iran in time, but some of Habib’s closest relatives were still in the country when he was executed. His son, Fereydoun (Fred), along with Fred’s wife, Eliane, and their son immediately went into hiding and needed a way to escape. Elghanayan’s description of the fallout of her grandfather’s murder reads almost like a hard-to-put-down thriller.

Iran’s Jews were terrified upon hearing news of Habib’s death, as they found themselves at risk of being associated with Israel and Zionism. One radio broadcast declared about Habib, “This alien spy was of great value to his overlords.”

There was nothing to do but for a delegation of Jews to visit Khomeini himself. That delegation included the late Hakham Yedidia Shofet, who founded Nessah Synagogue in Beverly Hills. During the meeting, Khomeini assured them that Iran’s Jews “had nothing to do with those bloodsucking Zionists.”

Differentiating between “good” and “bad” Jews is a dangerous antisemitic distinction that has only increased worldwide in the four decades since Habib was murdered on charges of “friendship with the enemies of God.” Jews in Iran today still have to denounce Israel and some are paraded around the country during anti-Israel rallies, holding hateful signs condemning Zionists (they don’t have much of a choice otherwise and still fear for their safety).

Readers will undoubtedly be moved by several alarming themes in “Titan of Tehran” that are as relevant today as they were in 1979: First, the death of Habib Elghanian was a reminder of the seemingly irreparable gap between the public and the private. A country’s large-scale revolution resulted in the death of thousands of individuals—fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, children and in Habib’s case, a cherished grandfather. The public may have moved on, but their loved ones still remain shattered. The night of Habib’s execution, Peter Jennings made a seemingly cursory announcement on “ABC’s World News Tonight” in which he said, “Elsewhere overseas today, there were more executions in Iran.” Her grandfather’s life and death, and the metaphoric death of Iranian Jewish history in Persia/Iran, were seemingly reduced to those two simple words (“more executions”).

The book is also a reminder that more than ever, Jews worldwide need their ears to the ground. Jewish and pro-Israel advocates who are sounding the alarm about those who nefariously distinguish between Jews and Zionists should refer to Habib’s murder. It was an arguable reminder of the dangers posed by antisemites who claim their only grievances are with Israel.

Finally, Elghanayan’s research is a testament to the suffering of the late-twentieth-century wandering Jew from the Middle East. Neither “white” nor associated with the Holocaust, these Jews are a reminder that at a time when most Americans were enjoying the pop culture of the 1980s, tens of thousands of Jews were fleeing for their lives from Middle Eastern dictators (as well as the former Soviet Union).

The Iranian government stripped Elghanayan’s family of citizenship. “Without our passports, we became stateless refugees overnight—even though Iran belonged to us as much as we belonged to Iran,” she writes. We need more voices and stories, like those of Elghanayan. In killing Habib Elghanian, the regime also killed the future of Jewry in Iran. His granddaughter has proven skillful and invested in bringing Habib’s story back to life.

“Gathering the facts and putting them down on paper is cathartic because clarity is comforting and writing is an active form of grieving,” Elghanayan said. “The fuel in this case was that I was rebuilding his life and death and that even though he was alone, the story would be with readers. They can also sit with the pictures of him at his trial where he’s fighting for his life, see what the firing squads at the prison courtyard looked like, and the photo of him after he died.”

Habib was the ultimate symbol of Iran’s most important asset: its own people. He was also the ultimate symbol of the people’s inevitable demise. But for Elghanayan, yearning for Iran is akin to a “toxic romanticism,” as she unequivocally declares, “Iran is no longer mine … I belong to America and … America belongs to me.”

The book will resonate with all readers, but should especially be read by American leaders contemplating our foreign policy toward Iran; by Jewish communal professionals seeking inclusivity of Persian and other Mizrahi Jews; and especially by college students, as well as young Iranian American Jews who were born in the U.S. but whose parents escaped Iran.

Ultimately, Elghanayan’s research is a heartening act of love. Few people know as many details about their parents’ lives as Elghanayan has uncovered about the life of her legendary grandfather.

Not wanting to abandon his own community, Habib didn’t live to see the mass exodus of Jews from Iran, an exodus that was triggered primarily by his execution. In January 2017, the most iconic physical legacy of Habib Elghanian—the Plasco Building, the tallest building in Iran— was consumed by a fire that killed over 20 firefighters. It fell to the ground in a torrent of flames and destruction.

The Plasco fire was a reminder of life in Iran under the regime: It destroys far more than it has ever built.

Tabby Refael is a Los Angeles-based writer, speaker and civic action activist. Follow her on Twitter @RefaelTabby