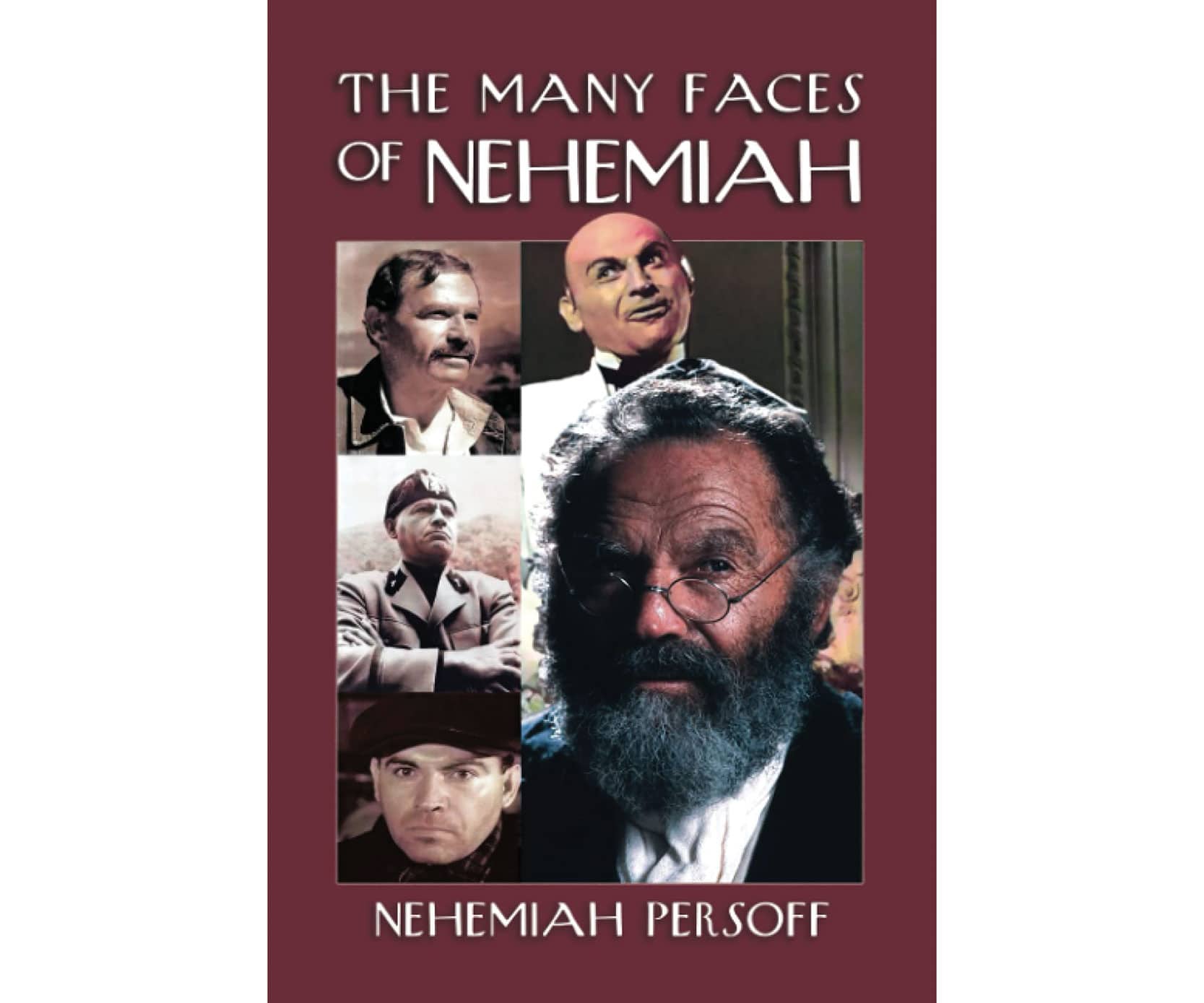

Born 102 years ago in Jerusalem, Nehemiah Persoff was the son of two founding members of the first Hebrew-language theater company in pre-state Israel. “[H]ardly a place to prepare one for the strains and stresses, the need to compromise one’s dignity and especially in a career as an actor on Broadway and in Hollywood,” the centenarian writes in “The Many Faces of Nehemiah Persoff” (Autumn Road Publishing). It’s an endearing and revealing memoir that pulls back the curtain on a deeply familiar face, one that we have seen in more than 200 movies, plays and television programs ranging from “Some Like It Hot” to “Yentl” and from “Magnum P.I.” to “Gilligan’s Island.”

Persoff’s father, an instructor at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, was sent to America in 1923 to promote the artwork that was being made by its students. By the age of ten, Nehemiah and the rest of his family had joined his father in New York. “I think I cried myself to sleep for about two years before I began to accept the fact that America was my new home,” he writes.

A comic scene from adolescence allows us to understand that Persoff was destined to become an actor. The family was not observant, but it was agreed that a bar mitzvah would be appropriate. “I recited the portion I knew by heart and I ad libbed,” he explains. “I double-talked the rest, thinking that chances are the people did not understand Hebrew.” He was wrong, and one old in the congregation could be heard to ask: “What? What did he say?” Another congregant replied: “Sha, the boy is from Jerusalem, this is the real Hevreet from Yerushalayim.”

Persoff charts his metamorphosis from a greenhorn into an American — and from an aspiring engineer into an accomplished actor — with the evocative scene-setting and story-telling that fleshes out the saga of the Jewish immigrant experience in America.

Persoff charts his metamorphosis from a greenhorn into an American — and from an aspiring engineer into an accomplished actor—with the evocative scene-setting and story-telling that fleshes out the saga of the Jewish immigrant experience in America. “My devotion to the ideals of the Zionists and the dignity of work with me constantly,” he writes. “I didn’t want to be a burden on my family by being an unemployed actor.” But he found himself equally devoted to his calling as a performer. He attended one class as a freshman at Cooper Union, and then enrolled in acting school.

His fate was sealed when he was invited to impersonate Karl Marx at a Communist party rally at Madison Square Garden. It was a walk-on role with no lines, but the charged-up crowd of 20,000 cheered for fifteen minutes. Clearly, they were applauding Marx, not Persoff, but it was enough to hook him on the pleasure of public adulation.

Persoff studied the Stanislavski Method with Stella Adler, and his hopes were elevated after his performance in a well-reviewed production at her school, the Dramatic Workshop. “The next morning, I got an invitation from Uncle Sam directing me to join the U.S. Army for a guaranteed long run,” he notes. After the war, he joined the Actor’s Studio, where his fellow actors included Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando and John Garfield.

The break-out moment in Persoff’s acting career came when Charles Laughton produced “Galileo” on the New York stage but was unable to persuade Marlon Brando to appear in the play. Persoff auditioned seven times before Laughton announced: “I can work with this actor, sign him up.” Recalls Persoff: “Next to becoming a member of the Actor’s Studio, this was the best thing that happened to me in my career as an actor and as a person.” Yet Laughton himself was unimpressed by Method acting: “Don’t pay attention to the crap they teach you at the studio,” he advised the young actor.

History intruded again and again into Persoff’s life. When the State of Israel declared its independence in 1948, Persoff told himself “if a war broke out, I would be fighting shoulder to shoulder with my Israeli brothers.” Yet he decided to “follow this dream, so close to becoming a reality.” Years later, when he worked as an actor in Israel, his fellow actors did not condemn him. “Yet,” he writes, “nothing can wipe out the pain and shame of the selfishness that I carry with me to this very day.”

One of the delights of the book is the inevitable name-checking of actors whom we know and admire. Persoff, for example, lost the money he had saved up to buy a refrigerator when Sidney Poitier invited him to join a poker game.

One of the delights of “The Many Faces of Nehemiah” is the inevitable name-checking of actors whom we know and admire. Persoff, for example, lost the money he had saved up to buy a refrigerator when Sidney Poitier invited him to join a poker game. It was Rod Steiger who proposed Persoff for what turned out to be his first role as a featured player in a Hollywood movie, “The Harder They Fall,” which turned out to be Humphrey Bogart’s final film, “Nicky, you’re on film now,” said the director, Marc Robson, after he lingered on the set after his first take. “Go home.” Nicky, as it happens, is Persoff’s nickname, but he also reveals that James Cagney who grew up near a Jewish neighborhood – preferred to address him as “boychik.”

But what Persoff does best of all is to infuse his memoir with ironic humor. When he auditioned for the role of a mohel in an episode of “L.A. Law,” for example, he told the director that he actually was a mohel when he was not acting.

“First, I practiced on a pea pod, then on a cucumber and slowly worked my way up to the real thing,” Persoff explained. “I’m sure you know that I am an actor; but I can’t always make a living at it, so I make up for that by doing some ‘moheling’ on the side.”

Needless to say, and just as he did on so many other occasions, Nehemiah Persoff got the part.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.