Daf Yomi, the daily study of the Talmud in its entirety, one page at a time, is an undertaking that lasts 7 1/2 years. When a newly divorced young woman named Ilana Kurshan first entertained the prospect of engaging in a Daf Yomi, she found it daunting.

“It was almost impossible to imagine my life in 7 1/2 years,” she writes in “If All the Seas Were Ink: A Memoir” (Picador). “Would I still be living in Israel? Would I still feel saddled by the pain and shame I carried around with me? Would I finally manage to ‘move on,’ as everyone around me kept assuring me I would?”

Kurshan, who had studied at Harvard and Cambridge and worked as an agent and an editor in New York, was not discouraged by the complexities and difficulties of the Talmud, but she was surprised to find that she was deeply inspired by what she found in its densely printed pages. “One need not even be Jewish or at all religious,” she explains. “Indeed, sometimes the rabbis are so bold and heretical that their statements may be best appreciated by those who are not themselves devout.”

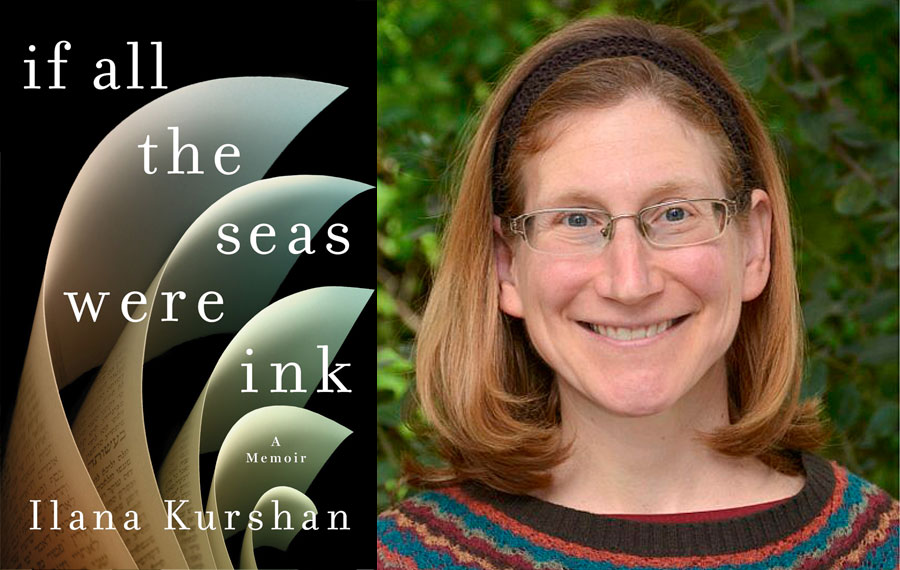

“If All the Seas Were Ink” — the title is derived from a paean to the glory of God written by a medieval rabbi — was richly honored upon publication in hardcover last year, winning the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and the Sophie Brody Medal for Achievement in Jewish Literature, and is now available in a quality paperback from the Picador imprint of St. Martin’s Press. What makes Kurshan’s book so compelling is the feat of literary alchemy she performs, turning the arguments and musings of ancient sages into what she calls an “ever-widening intersection of text and life.”

Indeed, the clue to understanding Kurshan’s book is the fact that she characterizes it as a memoir rather than a talmudic commentary. She reveals the stresses and torments in her own life, the people whom she has loved and those who have broken her heart; she describes the places she has lived and the work she has done in ways that come fully alive for the reader, sometimes poignantly and sometimes humorously; and she does it all in prose so rich and evocative that the book is fully rewarding even to readers whose interest in the Talmud may be slight.

Indeed, the sources and influences that she invokes may start with Hillel and Shammai but also include William Wordsworth and William Blake, D.H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf, Shel Silverstein and Amos Oz. She describes her “book of life” as consisting of her siddur, her day planner and the journals she has kept since childhood; the first one, she recalls, was a Rainbow Brite notebook. She confesses that she put certain books in her home library on the bottom shelf because she was embarrassed to own them: “Vegan With a Vengeance,” “The No-Gym Workout” and “How to Behave in Dating and Sex.”

Ilana Kurshan was not discouraged by the complexities and difficulties of the Talmud, but she was surprised to find that she was deeply inspired by what she found in its densely printed pages.

Then, too, the fact that Kurshan is a woman who studies Talmud is both provocative and significant. “[M]ost of the women in the Talmud are sexual objects who are seduced or raped or subjected to virginity tests,” she points out. “The few women who are depicted as learned — Yalta, Beruriah, Rav Hisda’s daughter — have surprisingly violent streaks, perhaps a testament to their force of personality.” And she describes her struggles with being a single woman, which seems to bother the people around her as much as it did the talmudic rabbis: “I didn’t mind being unmarried, but the thought of other people’s pity made me cringe,” she writes. “The Talmud, too, looks pitifully upon any woman who does not have a man with whom to share her life and, more specifically, her bed.”

The author is both knowledgeable about and respectful of pious tradition, but she also possesses a certain irreverence that sparkles throughout her book. She is dedicated to both exercise and Talmud, and when swimming laps in a pool, she left photocopied pages in protective plastic sleeves at the far edge so she could glance at a page of text before turning around. “I imagine the sages would have been none too pleased by my chanting Torah in a bathing suit in the Jerusalem public pool,” she writes — and then she makes a sly allusion to the romantic and even erotic lyrics of the Song of Solomon: “Many waters cannot quench my reverence for Torah, I imagined myself reassuring them, nor can rivers or pools sweep it away.”

By the end of Kurshan’s enchanting and illuminating memoir, we feel that we have come to know her as intimately as we have come to know the Talmud, which surely was her intention all along.

“I had to confront what I knew to be true: That I have always been a hopeless romantic, and that my sense of romance is deeply bound up in my passion for literature,” she writes. “I’d spent my whole life reading books, but here was a book I could imagine spending my whole life reading.”

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.