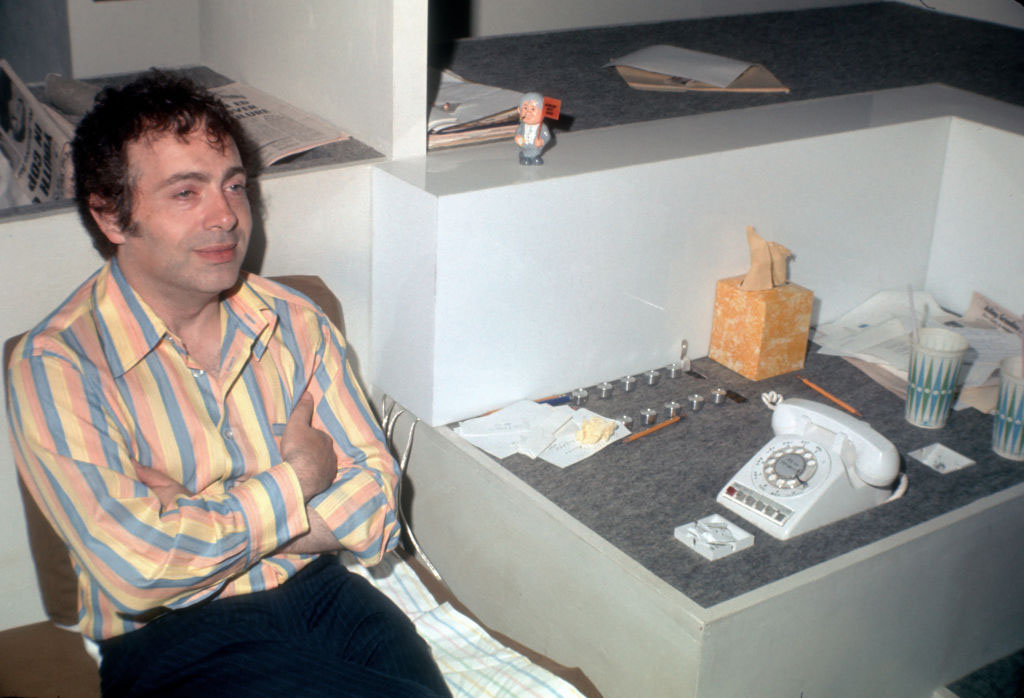

“I’M FROM WOODMERE. I’M JEWISH. I’M GAY.”

Harvey Milk often carried a sign with those words on marches during his activist days in the 1970s, his nephew Stuart Milk says. The first openly gay man in the country to be elected to public office “was not religious or observant, but Harvey absolutely identified himself as a Jew,” he said.

The San Francisco County supervisor, who was murdered in his City Hall office in 1978, also enjoyed conversing in Yiddish with Sharyn Saslafsky, who would come into his camera store in San Francisco’s Castro district as a customer or just to shmooze.

“Although neither of us spoke it fluently,” Saslafsky recalls, “we had fun using Yiddish to tell stories, laugh and talk about different things. We would use it interchangeably with English, correctly or incorrectly.

“We would also talk about Yiddishkayt, about what Judaism stresses,” she continues. “That was clearly very important to Harvey. I believe his concern for justice, fairness, equality and ethical behavior came from his Jewish background.”

The fact that he was Jewish is mentioned only briefly in the recently released biopic, “Milk,” which focuses instead on the personal and political events that occurred over the last eight years of Milk’s life.

Prior to that period, Milk, born in 1930, had played high school football, served in the Navy, worked on Wall Street, dabbled in the theater, been a Republican and led an essentially closeted life until he settled in San Francisco. There he transformed himself into a progressive gay activist at a time when violence and discrimination against gays were commonplace.

Many Hollywood filmmakers, including Oliver Stone, have contemplated making a movie about Milk. However, it wasn’t until a young writer named Dustin Lance Black finished a spec script based on extensive research that the project began to move forward.

Cleve Jones, one of Milk’s protégés, sent the script to Gus Van Sant, who enthusiastically agreed to direct the film and who brought the screenplay to Bruce Cohen and Dan Jinks, the team that produced the Oscar-winning film, “American Beauty.” Jinks, like Milk, is gay and Jewish and says they were on board immediately.

“I thought the idea of this ordinary man who was not raised to be a politician, and who was not a particularly good politician initially, becoming a tremendous leader at a time when leadership was so necessary was a spectacular story. I found it powerful and so moving. As soon as I read it, I knew I had to be part of it, and as I was going through the script, I started thinking about actors who could do it, and I kept going back in my mind to Sean Penn. Fortunately, he said ‘yes’ pretty quickly, in about three weeks.”

The movie is already creating Oscar buzz, particularly for Penn’s extraordinary performance in the title role. Filmmaker Rob Epstein, whose documentary, “The Times of Harvey Milk,” won an Oscar in 1984, particularly admires what he calls the tenderness of Penn’s portrayal.

“It’s not an impersonation,” observes Epstein, who knew Milk and who is also gay and Jewish, “but it’s a representative, composite portrait of his interpretation of Harvey, and I was very impressed by that. I also appreciate the intimacy of the film and the gentleness of it. That surprised me. This was Gus’ take on the story, and until I saw it, I couldn’t envision what it would be.”

“Milk,” which makes use of archival news footage that shows gays being rousted from bars by the police, is a narrative that begins in November 1978 with Milk, as he did in real life, tape-recording a final testament, presciently anticipating that he might not live to see his 50th birthday. The story then goes back eight years to New York, where he begins an affair with Scott Smith, 20 years his junior, and sorrowfully notes that he is 40 years old and hasn’t done anything important.

Seeking a fresh start, the two move to San Francisco and open their camera shop in the Castro district, a neighborhood that eventually becomes a haven for gays. The year is 1973, and the couple faces open hostility and discrimination.

Milk forges an alliance with the Teamsters Union, which is pitted against Coors Brewing Co. in a labor dispute, by persuading gay bar owners to boycott the beer. In return, the union agrees to send gay drivers out on jobs.

Feeling that leadership is lacking in the gay community, Milk launches his first of four political campaigns as an openly gay candidate with a bid for a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. He loses. After two more unsuccessful tries for public office, Milk finally wins a board seat in 1977.

The film is careful to stress that once elected, Milk became a supervisor for all the people, promoting such causes as inexpensive child care facilities and free public transportation, as well as advocating for seniors, minorities, labor and other powerless groups.

As Stuart Milk explains, that concern for the underdog stemmed from his uncle’s understanding of basic Jewish principles.

“He was 15 at the end of World II, and I can definitely say that he was deeply affected by the Holocaust,” Stuart Milk says. “So, yes, the Jewish sensitivity to civil rights absolutely had an impact on Harvey. In fact, he was the one who told me about how much support Jewish organizations and Jewish individuals gave to minorities. He often said that Jews feel they cannot allow another group to suffer discrimination, if for no other reason than that they might be on that list someday.”

“Furthermore,” he says, “Harvey was the first to tell me that in addition to the Star of David, which Jews were forced to wear in Nazi Germany, there were pink triangles that gays had to wear, and that almost a million gays were put to death.”

Milk’s last major battle, stirringly depicted in the film, was his successful campaign against Proposition 6, known as the Briggs Initiative after its sponsor, state Sen. John Briggs. The measure sought to ban gays and their supporters from teaching in the state’s public schools.

Little did anyone on the film know that it would be so relevant in the wake of Proposition 8, the recent state ballot measure that was successful in banning gay marriage, Jinks says.

“We wrapped production in March 2007, and gay marriage wasn’t legal in California until May. Proposition 8 wasn’t on the radar until well after that, so it’s been eerie that there are so many similarities between what happens in the film and what’s happening now in 2008.”

In addition, the movie highlights Milk’s insistence during the campaign against Proposition 6 that gays come out to everyone they know.

“There was a particular philosophy behind that tactic,” Jinks says, “the philosophy being that people were voting against gays because being gay was scary to them. They didn’t know what it was.

“There were all these scare tactics being used by the opposition,” he continues. “Harvey was saying that voters should be made aware that they already knew gay people. He felt it was the responsibility of gays to say, ‘Here I am. I’m actually your doctor. I’m actually your schoolteacher. I’m actually your lawyer. I’m actually your son.'”

It was also a matter of authenticity, says Stuart Milk, who will never forget the time he spent with his uncle in 1975, just after the funeral back East for Harvey Milk’s father. Stuart Milk, who is gay, was 15 at the time and had never come out. He merely told his uncle that he felt different, and, without bringing up the issue of being gay, his uncle gave him encouragement and support. Stuart Milk describes it as a beacon of spiritual advice that touched him to his inner core.

“He told me that when anyone tries to hide who they are or their authenticity, whether it concerns their religion, their background or their ethnicity, the world is lessened,” Stuart Milk recalls. “And he used a Native American phrase: ‘You are the medicine the world needs. No one else can duplicate that.’

“His words set me on a path, and I realized that those who feel different, whether they’re gay or they’re Jewish in a Christian country, are providing a tremendous benefit. They’re making their community and their society stronger through their differences, not through their sameness.”

That conversation created a deep bond and began a dialogue that continued long distance, but Stuart Milk never saw his uncle again.

On Nov. 27, 1978, a trembling and traumatized Dianne Feinstein, now a United States Senator, addressed a bevy of reporters:

“As president of the Board of Supervisors, it’s my duty to make this announcement. Both Mayor [George] Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed. The suspect is Supervisor Dan White.”

White and Milk had been at odds for months before the shooting. White had resigned but wanted to rescind the resignation, and Moscone had refused to re-appoint him to the board. Vivid archival footage of Feinstein’s announcement appears early in “Milk.”

As information about the murders spread, Epstein was in a store getting coffee. He went immediately to City Hall and then to the home of Harry Britt, who would succeed Milk on the Board of Supervisors, while a candlelight march was beginning.

“Another friend and I felt there should be a Jewish service, as well,” Epstein says, “and we contacted Temple Emanu-El, the big Reform synagogue in San Francisco. That set in motion the Jewish service that took place soon afterwards.”

His uncle’s murder was devastating for Stuart Milk, who learned of it when someone knocked on the door of his college dorm room and gave him the news.

“I have had other major losses in my life,” Stuart Milk says, “and with each loss we suffer, a door opens for us to change the way we view life. So with Harvey’s death, I stepped through that door, and I came out to people in my dorm and to other people at school. A week later, I came out to my parents. My father took it well, but my mother reacted as I think most Jewish mothers would. She cried.”

Stuart Milk has seen “Milk” several times and has nothing but praise for the way it depicts his uncle.

“I think the film does a wonderful job of portraying Harvey’s hopes and dreams, as well as those of the people who were there to support him,” he says. “I thought Sean did a tremendous job of showing Harvey’s unique ability to inject a slightly sarcastic, but good-natured sense of humor into some very serious and solemn occasions. All of the performances are very strong.

“I’ve also gotten to know Bruce and Dan, the producers. Their passion and commitment to presenting Harvey as he really was and to having his message continue to a new generation is simply amazing.”