“The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” isn’t the sort of film one might initially expect from David Heyman — the British producer who bought the rights to the “Harry Potter” books in 1997 and steered the film franchise to become the highest grossing in cinematic history.

Harry Potter, of course, is the eponymous, bespectacled orphan who attends the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry and battles the evil Lord Voldemort over the course of seven books and five films so far (three more are expected by 2011). The fantasy movies are set in an elaborate magical world filled with giants, sorcerers and all manner of special-effects beasts.

“The Boy in the Striped Pajamas,” based on a book by John Boyne and due in theaters Nov. 7, by way of contrast, is set during the very real historical period of the Holocaust. The story is told from the perspective of 8-year-old Bruno (Asa Butterfield), who is chagrined when his father (David Thewlis, who plays Remus Lupin in the “Potter” films) takes over as commandant of a remote labor-turned-death camp. The sheltered Bruno has no one to play with in his new environs, and so is fascinated by the children working on what he perceives as a “farm” far away in the distance. Overwhelmed with boredom and curiosity, he disregards admonitions to refrain from exploring the back garden and heads for the “farm,” where he meets Shmuel, a Jew his own age who lives a parallel, if alien life on the other side of a barbed wire fence. Bruno’s innocent questions about the camp lead to a forbidden friendship that has devastating consequences for both boys.

Although the milieu — which includes barracks and a gas chamber — is light years from Hogwarts’ fictional world, Heyman noted some thematic similarities. The Potter books are filled with metaphors for racism and ethnic cleansing — including characters who refer to wizards as “pure-bloods,” “half-bloods” or mudbloods (a racist slur meaning mixed or non-magical parentage). “And ‘The Boy in the Striped Pajamas’ explores issues of prejudice and ignorance — and ultimately, compassion and empathy,” Heyman, 47, said in a telephone interview from his London home. “It’s about how one engages with people who are ‘other’ — who are on the opposite side of the metaphorical fence.”

“I think a child’s window into the world of the Holocaust is interesting and unique,” he added of Bruno’s perspective. “There has only been one Holocaust, on the scale of what happened in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, but there have been many holocausts since then, and some are going on today. The point, for me, is about learning from history. And I think this story, which is so affecting in its novelty and simplicity, can resonate today.”

Heyman said he was also drawn to Boyne’s novel because “People who fight adversity and struggle to overcome difficult situations fascinate me. Shmuel, obviously, is a heroic character, but I think that Bruno having the courage to go against what his father decrees is perhaps courageous in its own way.”

Heyman’s own family story involves the overcoming of adversity and is set, in part, in Nazi Europe. The producer’s Jewish grandfather, Heinz Heyman (the original spelling may have been Heymann), was an economist, newspaperman and broadcaster based in Leipzig, who was one of the last announcers to speak out against Hitler in early 1933.

“He was on the radio, the authorities came for him, and he had to bicycle out of Germany,” the producer said. “When he arrived in England, he was at first interned in a camp because he was a German citizen.” Before long, Heinz Heyman was working as a journalist (eventually covering economics for The Economist and The Financial Times) and sent for his wife, Hania, and infant son.

Heyman was 6 when his grandfather died — at his typewriter — after completing an article that ran two days after his death as the lead story in the Times. Hania had earned seven college degrees (the last in economics from the London School of Economics) and encouraged David’s love of authors such as George Orwell and I.B. Singer. A passionate supporter of the state of Israel, she took her grandson to visit relatives in the Jewish state every year from age 6 to 12.

David Heyman’s childhood home was as steeped in cinema as it was in literature; his parents were renowned film producers who worked with and entertained celebrities such as Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Julie Christie and Richard Harris (the latter played Hogwarts headmaster Albus Dumbledore in the first two “Potter” films). Heyman remembered the hard-drinking, hard-living Harris as “a generous, warm, unpredictable man who was always incredibly kind to me and could tell a story like no other.”

Heyman did not become bar mitzvah when he turned 13 (his mother is not Jewish); in fact he attended the prestigious Westminster School, which is under the auspices of the Church of England.

“I had to go to Westminster Abbey every morning and sing hymns, which at the time I thought was a big pain in the a—,” he recalled with a laugh. “So I’d sing in this very loud, very flat voice. I didn’t appreciate that I was standing in this remarkable ancient building.”

* What’s so Jewish about Harry Potter?

* Is Harry Potter a Zionist conspiracy?

* Harry Potterstein?

He said he did appreciate the “Hogwarts-like” friendships, rivalries and quaint traditions he experienced at school, which was mostly housed in the Abbey’s former medieval monastery; on Shrove Tuesday, for example, the students fought for the largest chunk of an enormous pancake that was heaved over a beam in the assembly hall (the winner received a gold sovereign coin). Every morning, Heyman added, “I ate breakfast on wooden tables made out of the bottoms of the ships of the Spanish Armada.”

When his classmates went off to Oxford or Cambridge after graduation, Heyman chose to come to the United States to attend Harvard University, where, he said, he was better able to study a broad range of liberal arts. He majored in 20th-century history and art history, and began his career as a production assistant on a film his father helped produce, David Lean’s “A Passage to India.”

Heyman went on to work as a studio executive at Warner Bros. and United Artists and segued into producing with 1992’s “Juice,” about teenagers in Harlem, starring Tupac Shakur and Samuel L. Jackson. But, by 1996, he had tired of Los Angeles and decided to return to London to found his own company, Heyday Films, and to make movies that did not reflect what he calls “a ubiquitous Hollywood sensibility.” A voracious reader, Heyman intended to focus on adapting books: “They provide great source material because authors have distinctive voices, and because books are a concrete ‘thing’ you can send to movie executives.”

Heyman set up a modest office above a music shop in London, where a colleague chanced to read a review about a not-yet-published novel, “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” (its British title) and asked for a free copy in 1997. It was summarily tossed on the “low priority” shelf at the bottom of a bookcase.

“Then my secretary, who was fed up with the rubbish she had to read, remembered the good review, took the book home, and brought it up at a staff meeting. I said, ‘Bad title. What’s it about?’ And she said, ‘It’s about an 11-year-old who goes to wizard school.’ I thought that was a great idea, so I read it and fell in love.”

“I hadn’t a clue that the Potter books would become an international phenomenon,” Heyman continued, “but I loved the author’s voice, that the book didn’t talk down to kids and that it made me laugh. I also liked it because I had gone to a school that reminded me of Hogwarts. We’ve all had friends like Harry’s [hyper-studious] friend, Hermione Granger, and Ron Weasley, the good-time pal. The book talked about loyalty and friendship and courage and trust, which I most certainly related to. And it was the story of an outsider, an orphan, Harry, who must overcome adversity.

“I’ve felt myself to be an outsider as a British producer in Hollywood — and for personal reasons I won’t expose,” he added with a laugh.

Heyman promptly interested Warner Bros. in the project and won over author J.K. Rowling with the promise that he would remain faithful to her story and characters; he has consulted with her regularly to seek her advice, discuss any changes, and to vet the various directors and screenwriters he has hired for the films — a process made easier as the first book and its sequels became international best sellers.

“I regard myself as the protector of Jo’s books,” he said. Heyman, moreover, was instrumental in selecting Daniel Radcliffe to play Harry Potter, after auditioning hundreds of boy for the part. “I met Dan while we were both attending a play, and he was so right I didn’t even watch the show,” he recalled.

Entertainment Weekly recently named Heyman near the top of its list of the “50 smartest people in Hollywood,” stating that “he has done just about everything right … including bonding with author J.K. Rowling and wisely seeking her input. He helped find unexpected directors (e.g. Alfonso Cuarón, David Yates) who’ve kept things fresh. And he’s kept the cast intact through five films, without any of his three teenage stars succumbing to a Lohanesque episode…. The franchise’s success rests on a thousand micro-choices Heyman made, including creating a world, on set and on screen, where people want to be.”

Entertainment Weekly recently named Heyman near the top of its list of the “50 smartest people in Hollywood,” stating that “he has done just about everything right … including bonding with author J.K. Rowling and wisely seeking her input. He helped find unexpected directors (e.g. Alfonso Cuarón, David Yates) who’ve kept things fresh. And he’s kept the cast intact through five films, without any of his three teenage stars succumbing to a Lohanesque episode…. The franchise’s success rests on a thousand micro-choices Heyman made, including creating a world, on set and on screen, where people want to be.”

In the most recent film, 2007’s “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix,” 15-year-old Harry secretly trains classmates to fight the genocidal Lord Voldemort and his henchmen, the Death Eaters. Radcliffe has compared Harry’s fictional guerrilla group to the French Resistance; Heyman also sees parallels.

“The echoes of World War II occur throughout the film,” he said. “Voldemort and his followers are obsessed with the preservation of blood purity; they’re not Nazis but they recall the politics and attitudes of Nazi Germany. And aesthetically — although it’s a cliché — the [Death Eater] Lucius Malfoy and his family are blond, like Hitler’s ideal of the quintessential Aryan.” (Lucius Malfoy is played by Jewish actor Jason Isaacs.)

Heyman said he did not set out to make a movie that dealt more directly with the Holocaust, but then another unpublished manuscript — a book now titled “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas: A Fable” — arrived in his office around 2005. The John Boyne book would go on become an international best seller (sound familiar?).

Heyman said he was “so moved by the story, and thought it was a very interesting and fresh perspective on a topic we’ve seen so often before.”

Some observers have criticized the book (and now the movie) for trivializing the Holocaust, but Heyman hopes the film will lead viewers to become interested in the subject of the Holocaust in general.

“I hope they will go on to read books like ‘The Diary of Anne Frank,'” he said.

In the meantime, next up for Heyman is “Yes Man,” starring Jim Carrey, as well as three more Potter films and other projects. As the conversation concludes, the world’s most successful producer these days has a more immediate concern: bathing his infant son.

“I’m 47 years old and I’ve finally had a child,” said Heyman, who also has four stepchildren. “I’m going to treasure these bath times.”

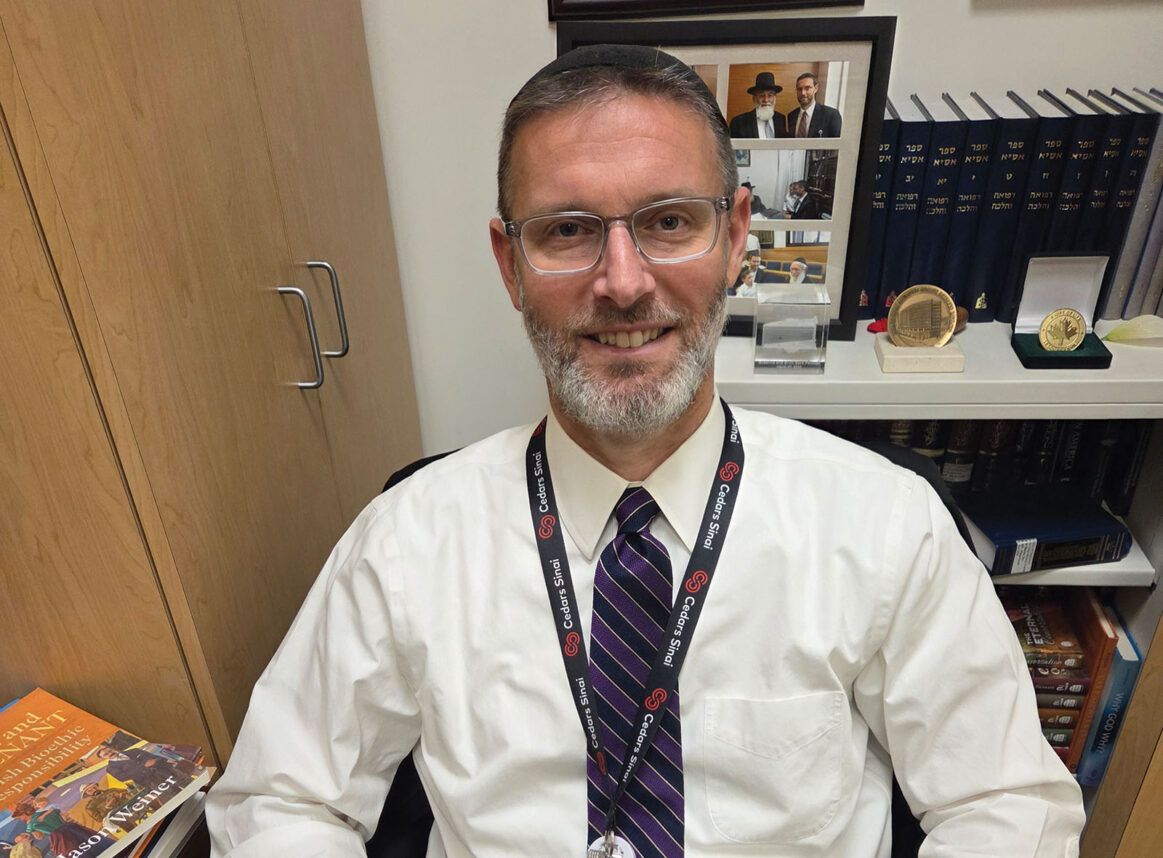

Photo above: David Heyman on the set of “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas.” Photo David Lukacs/Miramax Films