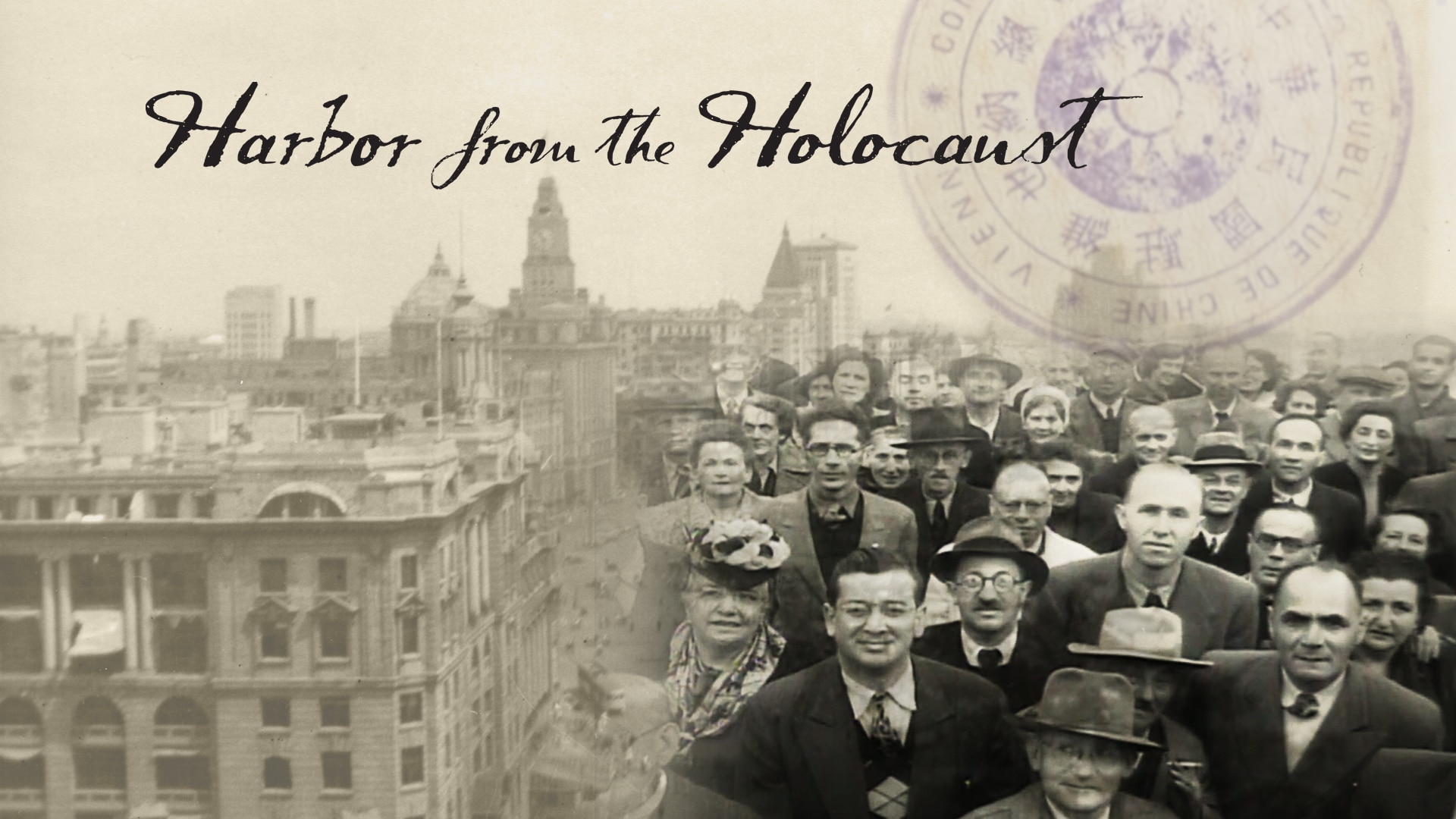

Tales of escape and survival from the Holocaust have long been the subject of books, movies and documentaries. But the story of the estimated 20,000 Jews who found sanctuary in Shanghai, China, is lesser known and it’s the subject of the PBS documentary “Harbor From the Holocaust,” premiering Sept. 8.

When the rest of the world closed its ports, the Japanese gave asylum to Jewish refugees, granting them access to the sector of Shanghai under their control, increasing the Jewish population — then mostly wealthy Iraqis and those who escaped the Russian Revolution — exponentially. But this haven was far from paradise, as depicted in the documentary’s archival footage and photos, writings and firsthand accounts from self-named Shanghai-landers and interviews with scholars.

“In every culture there are stories of people finding ways to preserve faith and family despite the odds,” executive producer Darryl Ford Williams, vice president of content at PBS affiliate WQED in Pittsburgh, told the Journal. “What was different and compelling about it to me was that this was clearly a story of life and resilience, people who had found a way out that was unexpected,” she said, noting that like herself, most people she knew — including Jews — had never heard it before. “That said to me that it was a story that needed to be told.”

She continued, “The people who could tell this story were very advanced in age, and many of them were losing the capacity to tell it. We wanted to share the privilege of sharing their stories while they are still alive. Some had more capacity than others and greater depth of memory. We looked for the oldest people we could find. One was former Treasury Secretary Michael Blumenthal. We ran out of batteries before he ran out of things to say.”

Among the other Shanghai-landers appearing in the film is Sigmund Tobias, a renowned research psychologist and professor who wrote about his experience in his 2000 book, “Strange Haven: A Jewish Childhood in Wartime Shanghai.” “Whenever I tell people about fleeing the Holocaust and being in Shanghai, they express a lot of incredulity because it’s not a well-known story,” Tobias told the Journal. “I was happy to tell it.”

Born in Germany to Polish immigrants, Tobias was almost 6 when his family arrived in China in 1938, soon after the horrors of Kristallnacht made it clear staying wasn’t an option. His father had been caught trying to cross the Belgian border and was sent to Dachau, but was let go on the condition he leave Germany. “He booked passage on a freighter, and my mother and I followed six months later,” Tobias, now 87, said. “We stayed for almost a decade.”

In the documentary, Tobias talks about his November 1946 bar mitzvah. “It was a great celebration, especially because we were so devastated, having just heard about the Holocaust. We knew nothing about it. We heard after the war,” he said. Raised “very Orthodox,” he rejected Judaism after the Shoah. “How could God permit that? I turned away from religion for a long time.”

At 15, Tobias left Shanghai alone, joining relatives who had survived Siberian work camps and made their way to the United States. “My parents thought that if I were in the U.S., it might be easier for them to come. I’d had no education except for yeshiva and I was working as an office boy at a company run by Jews in Shanghai. I wanted to resume my education.” He lived at an orphanage upon arrival and with a Jewish family in Brooklyn until his parents came over. He later got his undergraduate and graduate degrees from the City College of New York and a doctorate from Columbia.

“Whenever I tell people about fleeing the Holocaust and being in Shanghai, they express a lot of incredulity because it’s not a well-known story. I was happy to tell it.” — Sigmund Tobias

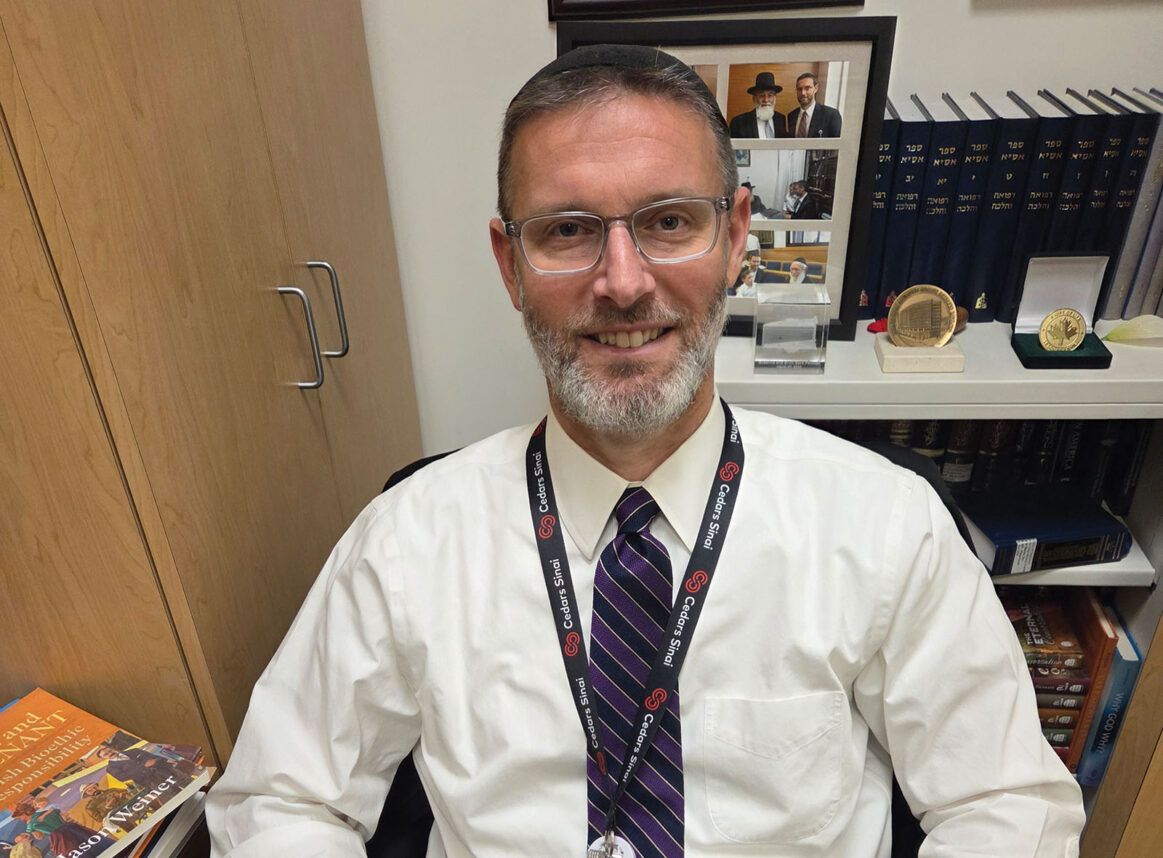

While teaching at Florida State University as a visiting professor in 1971-72, he met Rabbi Michael Berenbaum, now a Holocaust scholar and professor at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles. “He led a chavurah and I attended several times. That began my slow return to Judaism,” Tobias said, declaring himself “deeply identified with Judaism” today.

He and his wife belong to a progressive synagogue near their home in Sarasota, Fla. He stays in touch with a few fellow Shanghai-landers, and has participated in several reunions, including one on a cruise to Curaçao. In 1988, he returned to Shanghai as a visiting professor, lecturing at the Shanghai institute of education for a month.

Although living there among the Chinese and Japanese as a boy “was a new experience for me, I realized early on that even though we have different cultures and experiences, we’re all the same human beings underneath,” Tobias said. He remains grateful to the Japanese for refusing to comply with the Nazis’ plan to load the Shanghai Jews onto boats and torpedo them, and for providing sanctuary when none existed elsewhere.

Williams believes that the messages of “Harbor From the Holocaust” are particularly resonant today, in light of “the conversation that’s been going around the country about equality and the way we treat people, and what can happen when the worst in us is unleashed. These people survived this incredible experience and embodied remarkable resilience,” she said. “I hope this documentary inspires engaging with older people while we have them. Invite them to share their precious memories and life stories because there’s so much to be learned from them.”

“Harbor From the Holocaust” premieres Sept. 8 on PBS, PBS.org, and the PBS Video app.