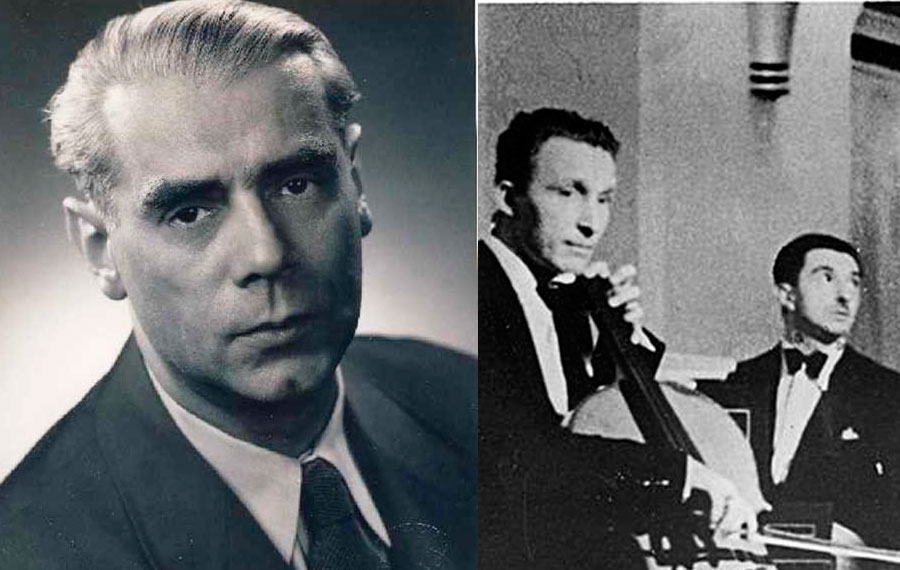

Every morning since 1936, All India Radio has started its broadcast day with the same music. With its droning strings and haunting violin, the tune sounds quintessentially Indian. But it was a Jewish emigré from Czechoslovakia, Walter Kaufmann, who composed it.

That story was the first of several surprises revealed at “From India to Indiana: Melding Music,” a lecture and concert presented by UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music at Schoenberg Hall on Feb. 27. Before an audience of about 300 people, the ARC Ensemble, a Canadian group that specializes in shining a light on musical works suppressed or marginalized under the 20th century’s repressive regimes, performed six of Kaufmann works that he composed while living in India from 1934–1946. Unlike that radio theme song, however, the Indian influences in the other pieces were easy to miss — a subtle droning cello line or a fluttery violin melody would only occasionally emerge from being tucked inside the music.

After Kaufmann left India, he moved to London, then Canada, where he spent 10 years leading the Winnipeg Symphony before finally becoming a faculty member at Indiana University. He died in 1984 at the age of 77.

Before the concert, UCLA ethno-musicology professor Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy summarized what she called Kaufmann’s “magnificent life in music.” He wrote scores for early Indian films, worked at All India Radio as the head of its European music department, started the Bombay Chamber Music Society and traveled throughout India seeking out the country’s various musical styles.

William Lazer, Kaufmann’s brother-in-law, told the Journal in a phone interview that when Kaufmann took an interest in a subject, he became an “authority,” incorporating much of what he heard into his own compositions.

Simon Wynberg, ARC’s artistic director, said the music Kaufmann wrote in India “jumps out at you immediately,” describing it as a “mix of his Western training and his enthusiasm for Indian music.” ARC plans to record a selection of Kaufmann’s music, with an expected release in spring 2020.

“[Kaufmann was] never impressed with money. He was never impressed with ceremony and he was never impressed with honors.”

—William Lazer

Although Kaufmann had well-known peers, including Albert Einstein, who wrote references for Kaufmann when the composer was trying to immigrate to America, his work is not well known, partly because he did little to promote his creations. He also tended to, well, follow his own tune. The trends in post-World War II classical music — such as serialism and minimalism — did not interest him, which was another reason why, despite composing throughout his life, only a five-minute recording of his music exists, Wynberg said.

“[Kaufmann] was an incredibly modest and self-effacing kind of man,” who never even bothered to publish his music, Wynberg said. “He finished one piece and then it was onto the next.” Kaufmann even stipulated that “The Scarlet Letter,” the well-received 1959 opera he wrote based on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, could be performed only at Indiana University.

William Lazer’s daughter, Simone, who traveled from Nashville for the concert, said Kaufmann, her uncle, was “a gentle genius” who at parties took more joy in playing with the children than talking to adults.

Kaufmann, William Lazer said, was “never impressed with money. He was never impressed with ceremony, and he was never impressed with honors. He loved to do research and he loved to write music.”

Neither of the Lazers remembered Kaufmann as especially religious, but Wynberg commented dryly: “If he didn’t identify as Jewish, others did it for him.”

Asked how Kaufmann would have responded to the renewed interest in him and his music — in addition to ARC’s projects, Kaufmann was a character last year in an off-Broadway play, “The Music in My Blood” — William Lazer said the composer probably would have shrugged it all off with a Yiddish grunt: “Nu?”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.